In 1906, Alois Alzheimer, a psychiatrist and neuroanatomist, reported to a gathering of psychiatrists in Tubingen, Germany, of “a peculiar serious disease process of the cerebral cortex.” The case involved a 50-year-old woman who suffered from memory loss, delusions, hallucinations, aggression and confusion – which worsened until her untimely death five years later.

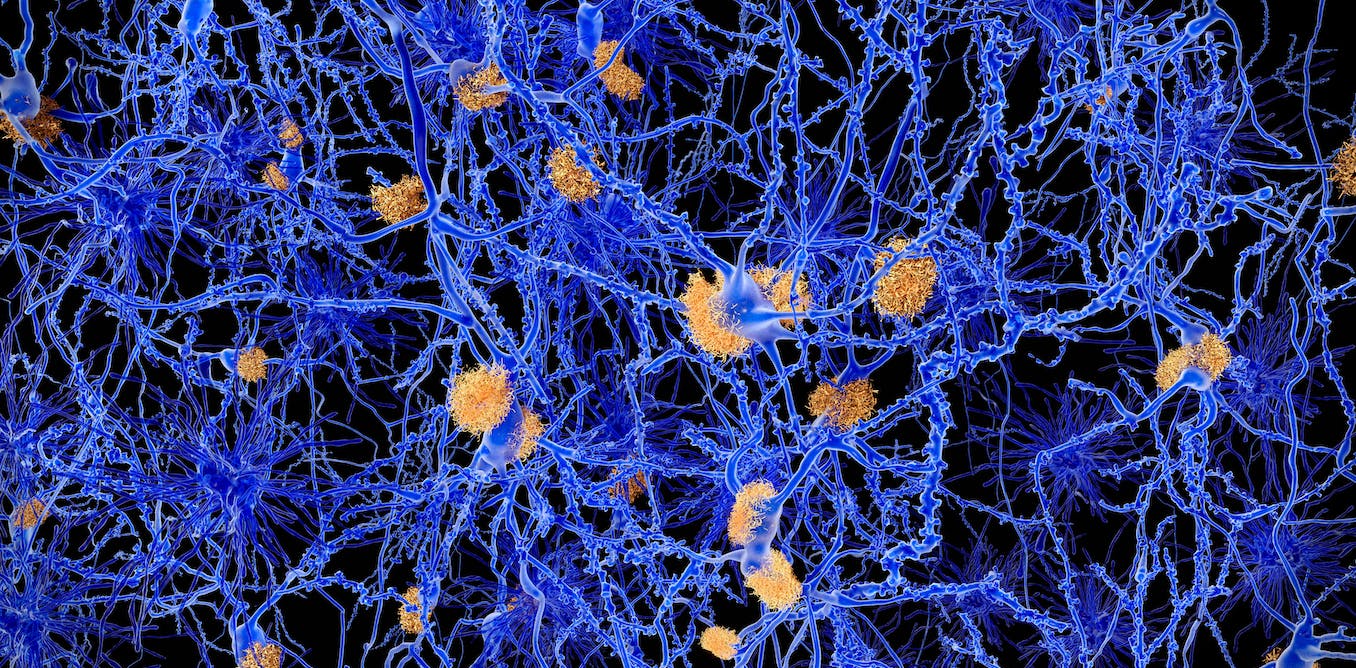

At the autopsy, Alzheimer noticed prominent plaques in her brain. These plaques – clumps of amyloid beta protein – are still believed to be the cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

However, this theory has two major problems. First, it doesn’t explain why many people (even old people) have plaques in their brains without any neurological symptoms like memory loss. Second, clinical trials for drugs that reduce these plaques have been unsuccessful—with one recent exception, but more on that later.

When amyloid beta protein builds up in the form of plaques (insoluble clumps), the original soluble form of the protein, which performs important functions in the brain, is used up and lost. Some studies have shown that reduced levels of soluble amyloid beta — called amyloid beta 42 — have resulted in poorer clinical outcomes in patients.

In a study recently published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, we examined whether the amount of plaque in the brain or the amount of amyloid beta 42 remaining is more important in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

To answer this question, we examined data from a group of people who have a rare inherited gene mutation that puts them at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Participants were from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network cohort study.

We found that breaking down amyloid-beta 42 (the functional version of amyloid-beta) is more damaging than the amount of plaque (the insoluble clumps of amyloid-beta).

Participants were followed for an average of three years, and we found that those with high levels of amyloid beta-42 in their cerebrospinal fluid (the fluid around the brain and spinal cord) were protected and their cognition was maintained over the study period. This is consistent with many studies showing important functions of amyloid beta 42 in memory and cognition.

It’s also relevant because we studied people with the genetic mutation who develop Alzheimer’s disease, a group thought to be the strongest evidence to suggest that amyloid beta plaques are harmful. But even in this group, those with higher levels of amyloid beta-42 in their cerebronspinal fluid (CSF) remained cognitively normal, regardless of the amount of plaque in their brain.

It’s also worth noting that in some rare, inherited forms of Alzheimer’s disease — for example, in carriers of the so-called Osaka gene mutation or the Arctic mutation — people with low levels of amyloid beta-42 and no detectable plaques can develop dementia. This suggests that plaques are not the cause of her dementia, but low amyloid beta-42 levels could be.

AGF Srl / Alamy Stock Photo

Lecanemab – the only current exception

How will our findings impact drug development and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease? Until the most recent trial of lecanemab, an antibody drug that reduces plaques, all drug trials for Alzheimer’s disease have failed.

Some drugs have been designed to lower levels of amyloid-beta 42 based on the idea that patients will accumulate fewer plaques when levels of the normal protein are reduced. Unfortunately, these drugs often aggravated the patient’s condition.

Lecanemab was recently reported to have a small but significant effect in reducing cognitive decline. According to previous studies, this drug increases levels of amyloid beta 42 in CSF. Again, this is consistent with our hypothesis that increasing normal amyloid protein may be beneficial.

We will know more when the results of the lecanemab study are released. At the moment we only have a press release from the manufacturers of the drug.

We believe it will be important for future studies to focus on the levels of amyloid beta 42 and whether there is a benefit in increasing its levels and restoring them to normal rather than specifically removing it. This could be achieved with amyloid beta-42-like proteins – so-called “protein analogues” – but which clump together less than the natural ones.

This active protein replacement approach could become a promising new treatment avenue for Alzheimer’s and other protein aggregation diseases such as Parkinson’s and motor neuron diseases.

#Alzheimers #disease #Surprising #theory #causing

Leave a Comment