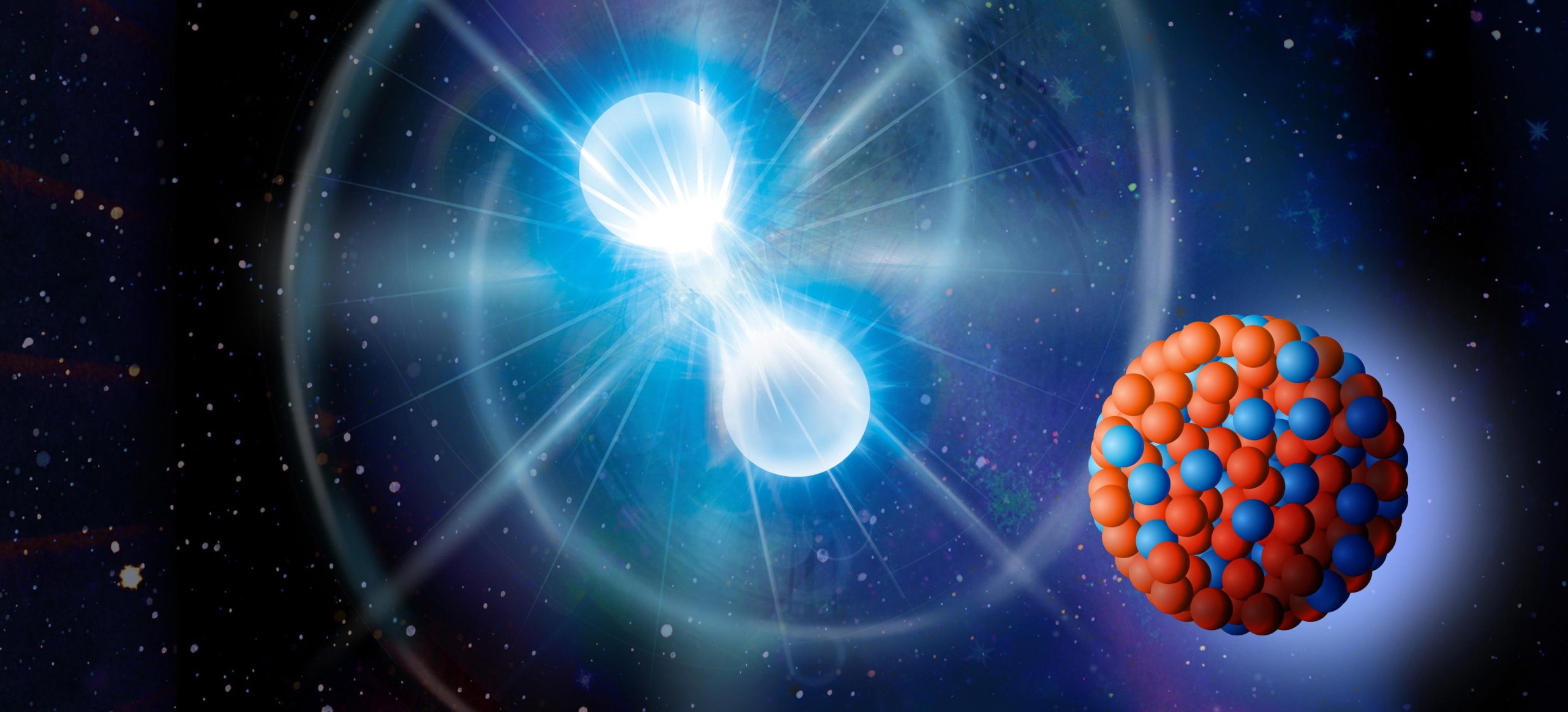

When a star dies, the violent end can result in the birth of a neutron star. Neutron stars are real heavyweights in the universe – a teaspoon of the celestial body, which is several kilometers across, would weigh a billion tons. There is an unimaginable difference in size between the atomic nucleus of the isotope lead-208 and a neutron star, but it is largely the same physics that describes their properties. Chalmers researchers have now developed a new computational model to study the atomic nucleus of lead. The 126 neutrons (red) in the nucleus form an outer shell that can be called the skin. How thick the skin is is related to the strong power. By predicting the thickness of the neutron skin, knowledge can be expanded about how the strong force works – both in atomic nuclei and in neutron stars. Photo credit: JingChen | Chalmers University of Technology | Yen Strandqvist

It is believed that massive neutron stars colliding in space can produce precious metals such as gold and platinum. Though the properties of these stars are still a mystery, the answer may lie beneath the skin of one of Earth’s smallest building blocks — a lead nucleus. Always the core of

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[{” attribute=””>atom to reveal the secrets of the strong force that governs the interior of neutron stars has proven difficult. Now a new computer model from

The strong force plays the main role

Despite the immense size difference between a microscopic atomic nucleus and a neutron star several kilometers in size, it is essentially the same physics that governs their properties. The common denominator is the strong force that holds the particles – the protons and neutrons – together in an atomic nucleus. The same force also prevents a

Andreas Ekström, Associate Professor, Department of Physics, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden. Credit: Chalmers University of Technology | Anna-Lena Lundqvist

A reliable way to make calculations

“To understand how the strong force works in neutron-rich matter, we need meaningful comparisons between theory and experiment. In addition to the observations made in laboratories and with telescopes, reliable theoretical simulations are therefore also needed. Our breakthrough means that we have been able to carry out such calculations for the heaviest stable element – lead,” says Andreas Ekström, one of the main authors of the article and Associate Professor at the Department of Physics at Chalmers.

The new computer model from Chalmers, developed together with colleagues in North America and England, now shows the way forward. It enables high-precision predictions of properties for the isotope* lead-208 and its so-called ‘neutron skin’.

Christian Forssén, Professor, Department of Physics, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden. Credit: Chalmers University of Technology | Anna-Lena Lundqvist

The thickness of the skin matters

It is the 126 neutrons in the atomic nucleus that form an outer envelope, which can be described as a skin. How thick the skin is, is linked to the properties of the strong force. By predicting the thickness of the neutron skin, knowledge can increase about how the strong force works – both in atomic nuclei and in neutron stars.

“We predict that the neutron skin is surprisingly thin, which can provide new insights into the force between the neutrons. A groundbreaking aspect of our model is that it not only provides predictions, but also has the ability to assess theoretical margins of error. This is crucial for being able to make scientific progress,” says research leader Christian Forssén, Professor at the Department of Physics at Chalmers.

Model used for the spread of the coronavirus

To develop the new computational model, the researchers have combined theories with existing data from experimental studies. The complex calculations have then been combined with a statistical method previously used to simulate the possible spread of the coronavirus.

With the new model for lead, it is now possible to evaluate different assumptions about the strong force. The model also makes it possible to make predictions for other atomic nuclei, from the lightest to the heaviest.

The breakthrough could lead to much more precise models of, for example, neutron stars and increased knowledge of how these are formed.

“The goal for us is to gain a greater understanding of how the strong force behaves in both neutron stars and atomic nuclei. It takes the research one step closer to understanding how, for example, gold and other elements could be created in neutron stars – and at the end of the day it is about understanding the universe,” says Christian Forssén.

Notes

*Isotope: An isotope of an element is a variant with a specific number of neutrons. In this case, it is about the isotope lead-208 which has 126 neutrons (and 82 protons).

Reference: “Ab initio predictions link the neutron skin of 208Pb to nuclear forces” by Baishan Hu, Weiguang Jiang, Takayuki Miyagi, Zhonghao Sun, Andreas Ekström, Christian Forssén, Gaute Hagen, Jason D. Holt, Thomas Papenbrock, S. Ragnar Stroberg and Ian Vernon, 22 August 2022, Nature Physics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41567-022-01715-8

During the study, the researchers worked at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, Durham University in the UK,

The research has been carried out using some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers. The Chalmers researchers have mainly been funded by the Swedish Research Council and the European Research Council.

Leave a Comment