On some moonless nights, vast patches of the northwestern Indian Ocean and the seas around Indonesia begin to glow. This event was witnessed by hundreds of sailors, but only one research vessel has ever stumbled upon this bioluminescent phenomenon known as milky seas, purely by accident. Thanks to this vessel, samples showed that the source of the light was a bacterium called V. harveyi, which had colonized a microalgae called Phaocystis. But that was in 1988, and researchers have yet to be in the right place and time to retrace any of those events.

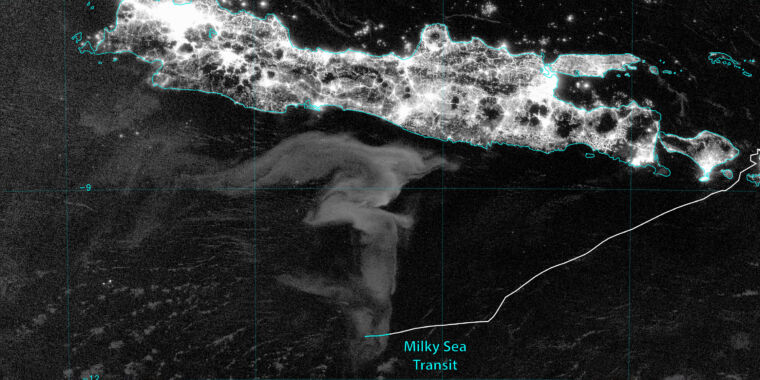

Both bacteria and algae are found in these waters, so it’s not clear what triggers these rare events. To understand why milky seas form, researchers have gotten much better at spotting these plumes of bioluminescence from the sky. With the help of satellites, Stephen Miller, a professor of atmospheric sciences, has been collecting both images and eyewitness accounts of milky seas for almost 20 years. Thanks to improvements in imaging capabilities over the past few decades, Miller last year published a compilation of likely milky seas over the period 2012-2021, including an occurrence south of Java, Indonesia, in the summer of 2019.

But those satellite observations lacked surface confirmation — that is, until the yacht’s crew Ganesha approached Miller with her first-hand account of what she experienced during her voyage through the seas around Java in August, recently published in PNAS. Their confirmation from eyewitnesses – along with the first photos of a milky sea – show that these satellites are indeed a powerful tool for detecting these events.

Heaven’s Eyes

Although milky seas can be massive – more than 100,000 square kilometers in the case of the 2019 sighting – the intensity of this bioluminescence is still relatively faint. By comparison, the more familiar sea sparkle from marine plankton (dinoflagellates) is 10 times stronger — and even that can be difficult to spot.

To map milky seas by satellite, researchers like Miller and his collaborators had to wait for the Day/Light Band to be installed on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) latest-generation environmental satellites. This low-light imager is sensitive enough to capture light that is 10,000 times fainter than reflected moonlight and about 1 billion times fainter than reflected sunlight. Day/Light Bands have been installed on two satellites: the Suomi National Polar-Orbiting Partnership (launched 2011) and the Joint Polar Satellite System series (launched 2017).

These satellites allowed Miller to search 10 years of satellite data, during which he found 12 suspected milky seas between 2012 and 2021. This data showed that the events could last for weeks and often coincided with regional monsoons and algal blooms created by the upwelling of nutrient-rich waters.

“Although milky seas are a spectacular visual phenomenon with an interesting historical backstory connected to maritime folklore, I think that in modern times we are also very interested in understanding how and why this massive expression of our biosphere is connected.” with primary production (the very base of the marine food chain),” Miller wrote in an email to Ars Technica. “I want to translate this into a better awareness of the atmosphere/ocean/biosphere coupling in the Earth’s climate system, so that we can begin to understand how fundamental components of our planet’s ecosystem may respond to a changing climate.”

But all of Miller’s observations were from over 500 miles (800 km) up in the sky—until he heard about the Ganesha Crew.

#Satellite #images #happy #boat #trip #give #information #glowing #seas #milk

Leave a Comment