Many of us accept that science is a reliable guide to what we should believe – but not all of us do.

Distrust of science has fueled skepticism on several key issues, from climate change denial to vaccine reluctance during the COVID pandemic. And while most of us may be inclined to dismiss such skepticism as unwarranted, it begs the question: Why should we trust science?

As a philosopher specializing in the theory of science, I am particularly interested in this question. As it turns out, delving into the works of great thinkers can help uncover an answer.

Common arguments

One thought that might initially come to mind is that we should trust scientists because what they say is true.

But there are problems with that. One is whether what a scientist says is actually true. Skeptics will point out that scientists are only human and are still prone to error.

Also, if we look at the history of science, we find that what scientists believed in the past often turned out to be wrong later on. And this suggests that what scientists now believe may one day turn out to be wrong. After all, there were times in history when people thought mercury could treat syphilis and the bumps on a person’s skull could reveal their character traits.

Shutterstock

Another tantalizing suggestion as to why we should trust science is that it is based on “fact and logic.”

That may be true, but unfortunately it is of little help in convincing anyone who is inclined to reject the statements of the scientists. Both sides in an argument will claim that they have the facts on their side; It is not unknown for climate change deniers to say that global warming is just a “theory”.

Read more: Vaccination hesitancy: Why “own research” doesn’t work, but reason alone doesn’t change your mind

Popper and the scientific method

One influential answer to the question of why we should trust scientists is because they use the scientific method. This naturally begs the question: what is the scientific method?

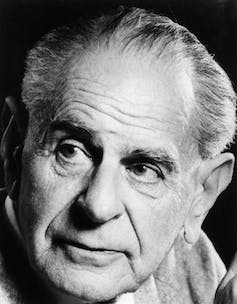

Perhaps the best known account comes from the philosopher of science Karl Popper, who influenced an Einstein Medal-winning mathematical physicist and Nobel Prize winner in biology, physiology and medicine.

Wikipedia

For Popper, science starts with what he calls “conjectures and refutations”. Scientists are presented with a question and offer a possible answer. This answer is a guess in the sense that it is not known, at least initially, whether it is right or wrong.

Popper says scientists then do their best to disprove that conjecture or prove it wrong. Typically, it is refuted, discarded, and replaced with a better one. This will also be tested and possibly replaced by an even better one. This is how science advances.

Sometimes this process can be incredibly slow. Albert Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves more than 100 years ago as part of his general theory of relativity. But only in 2015 scientists managed to observe them.

For Popper, the core of the scientific method is the attempt to refute or disprove theories, which is referred to as the “falsification principle”. If scientists, despite their best efforts, cannot disprove a theory over a long period of time, then the theory is, in Popper’s terminology, “confirmed”.

This suggests one possible answer to the question of why we should trust what scientists tell us. That’s because, despite their best efforts, they haven’t been able to refute the idea they tell us is true.

majority rules

Recently, an answer to this question was further articulated in a book by science historian Naomi Oreskes. Oreskes recognizes the importance Popper attaches to attempting to refute a theory, but also emphasizes the social and consensual element of scientific practice.

For Oreskes, we have reason to trust science because or to the extent that there is consensus among the (relevant) scientific community that a particular claim is true – which same scientific community has done its best to support it refute, and failed .

Here is a brief sketch of what a scientific idea typically goes through before consensus is reached that it is correct.

A scientist might give colleagues a paper on an idea, which they then discuss. A goal of this discussion will be to find something wrong with it. If the work passes the test, the scientist could write a peer-reviewed paper on the same idea. If the reviewers think it is sufficient, it will be published.

Others can then subject the idea to experimental testing. If there are a sufficient number of these, a consensus can emerge that it is correct.

A good example of a theory undergoing this transition is the theory of global warming and human influence on it. As early as 1896, it was suspected that increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere could lead to global warming.

In the early 20th century, another theory emerged that not only was this happening, but that carbon dioxide released by human activity (namely, burning fossil fuels) could accelerate global warming. It received some support at the time, but most scientists remained unconvinced.

However, in the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st century so far, the theory of human-caused climate change has passed ongoing tests so successfully that a recent meta-study found more than 99% of the relevant scientific community to accept its reality. It may have started as a mere hypothesis, passed tests successfully for more than a hundred years, and has now found near-universal acceptance.

The final result

That doesn’t necessarily mean that we should accept uncritically everything scientists say. There is, of course, a difference between a single isolated scientist or a small group saying something and a consensus within the scientific community that something is true.

And of course, for a variety of reasons – some practical, some financial, some others – scientists may not have done their best to disprove an idea. And even when scientists have repeatedly tried and failed to disprove a particular theory, the history of science indicates that it may be proven wrong at some point in the future as new evidence comes to light.

So when should we trust science? Popper, Oreskes, and other authors in this field seem to take the view that when, despite their own efforts to refute an idea, there is a consensus that we have a good but fallible reason to trust what scientists say she is true .

Read more: Curious kids: What’s the most important thing a scientist needs?

#trust #science #doesnt #trust

Leave a Comment