This first-person article is the experience of Tiffanie Tri, a writer, political leader, entrepreneur and community builder in Ottawa. For more information on CBC’s first-person stories, visit the FAQs.

If you asked me when I knew my family were refugees, I couldn’t tell you. There wasn’t a single moment of realization – just scattered memories like jigsaw pieces that don’t always seem to fit together.

When we were kids, my parents told my sisters and I about their harrowing journey escaping soldiers and pirates, surviving the stormy waters of the South China Sea, and arriving in Hong Kong.

After nine days at sea, they waited another three days on the ship outside the city gates until the United Nations intervened and they were finally allowed to disembark. They stayed in a refugee camp for four months before being promoted to come to Ottawa in 1979.

When I heard these stories, I always felt that they were new adventures that were somehow far removed from my life in Canada. As a child, I didn’t have the historical knowledge or understanding to anchor their meaning.

Little was taught about the Vietnam War in school—just a few phrases sprinkled here and there in history books. Films about the Vietnam War have always been told through the eyes of American soldiers in the jungles of Vietnam, ripe for cinematic shots of mud, blood and glory.

None of these Oscar-worthy performances matched the stories I’d heard from my family, who, despite the melancholy, kept alive slivers of hope and humanity.

I guess it was no surprise that my fleeting interest gave way to a slight ambivalence.

Ask my grandfather

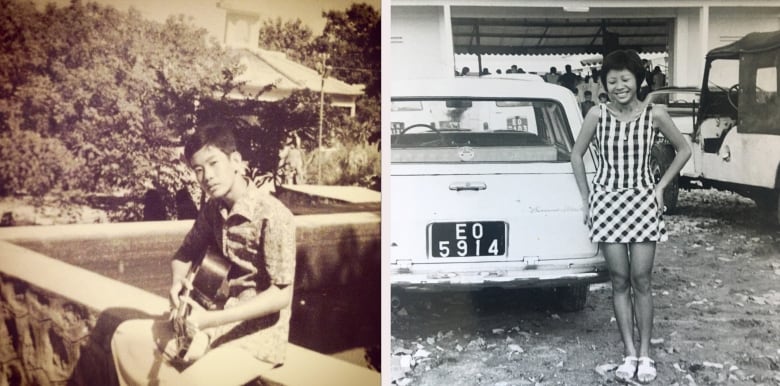

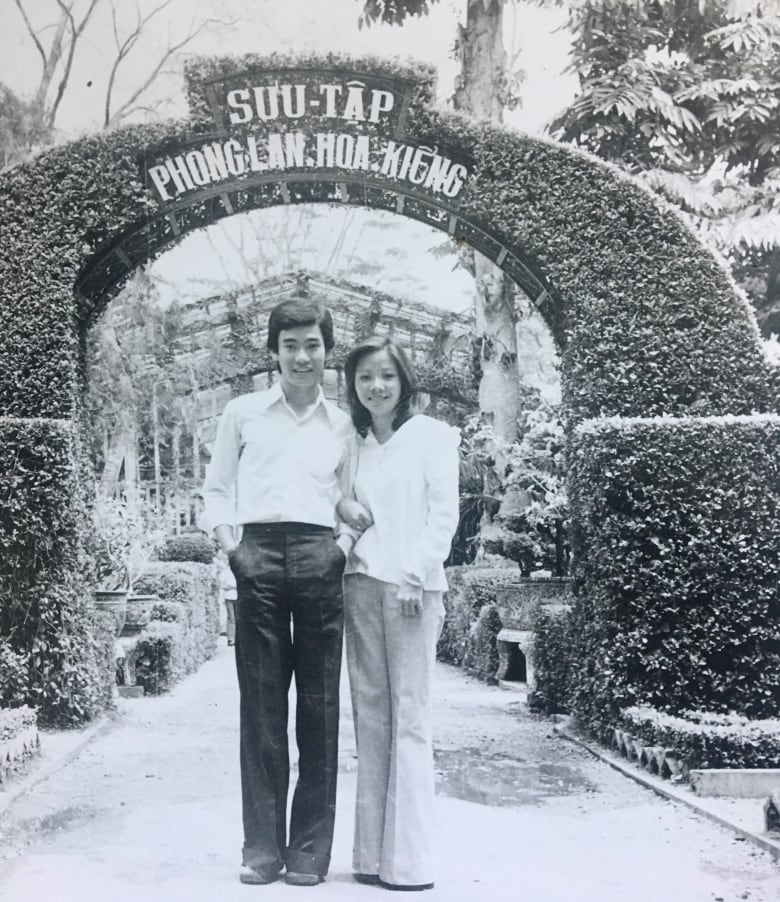

My maternal grandfather was the driving force behind moving our family to the other side of the world. My parents were dating at the time and my father joined my mother’s family on the perilous journey, leaving his own parents behind. They surrendered their fate to the ocean and the immigration system.

Even though my parents shared their stories about what happened, it felt important to hear my grandfather’s perspective. He didn’t talk much about his past. Perhaps it was the loss of my grandmother just a few years after I arrived in Canada, or perhaps the suffocating humility of starting over made him want to talk about his life.

- Do you have a compelling personal story that can inspire understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Send us an email with your pitch.

At family gatherings, the obligatory greeting was “Hello gong gong!”

“That’s good, that’s good,” he said in return, nodded appreciatively and waved us away at the same time.

The first time I heard him share his story was when he was baptized at the age of 89. The faintest trace of emotion crept into his voice as he spoke of how life changed drastically during the war, of imprisonment and the numerous attempts he made to get his family out of the country.

With their savings dwindled by blackmail and exorbitant prices charged by smugglers for a chance at freedom, my family made a last-ditch attempt to leave Vietnam. They moved like shadows aboard a boat with several hundred people. After nine days at sea, a violent storm devastated the boat and many passengers lost consciousness.

When he came alive the next morning, my grandfather couldn’t believe it. “Even so, we still couldn’t die!” he crowed in disbelief, still confused after all these years.

pandemic time

Increasingly, I felt a pull, a nagging feeling that I needed to document these stories and honor that determination and resilience.

I would shrug off those feelings to prioritize the hustle and bustle of everyday life. It wasn’t until the pandemic brought all events and activities to a standstill that I felt like I had enough time.

I decided to record this story after meeting a film producer and director whose family also moved to Canada during the Vietnam War.

The process wasn’t easy. We connected with my grandfather via Zoom to learn more about his story while my parents acted as translators across languages and generations.

We peppered him with our list of prepared questions, sometimes impatiently waiting as he stoically reminisced as ever.

Towards the end we asked him what he misses most about Vietnam. Taking a moment to think, he said: “It’s hard to remember. Life feels like a dream.”

I had more questions but could see that he was slacking off as his answers became shorter and shorter. We said good night and ended the call.

That was the last time I spoke to him. Four weeks later he was gone. Just as I had begun to tear down the walls he had built around his memories and perhaps his heartache, I found myself left with the ashes of what could have been.

I spent months chiding myself for waiting so long to document his story, for waiting for the perfect conditions to come together, and now it was too late.

loss and disentanglement

As I grieve, a question echoes in my mind, a question that director Han Nguyen asked during our initial conversations. “When do past and present meet before splitting up again?”

This is what I think of as I walk through Ottawa’s Chinatown, where my grandfather lived for the last decades of his life, where Chinese herbal and acupuncture shops are slowly being replaced by trendy storefronts of microbreweries and cannabis dispensaries.

The new building will leave my grandfather’s footprints even as I cling to the past. And it dawns on me, maybe there isn’t a single moment where past and present meet. Instead, every step we take is a collision, every breath an interaction between past and present, a tight negotiation of our future.

It’s either a banal travesty or an immense privilege, depending on how you look at it.

My message now is simple. Talk to your living ancestors. Discover the stories of how they moved mountains, sliced through oceans and stared sideways.

And know that the same strength lies within you.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can inspire understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. You can pitch us here.

#PERSON #family #fled #Vietnam #Canada #time #started #questions #late #CBC #News

Leave a Comment