A lymphoma is a neoplasm of lymphoid tissue resulting from the proliferation of malignant B and T lymphocytes. It usually originates in lymph nodes but can start in any organ in the body. Extranodal lymphoma is defined as involving organs and structures other than lymph nodes, such as the B. Spleen, thymus and pharyngeal lymph ring [1]. Differentiating disseminated disease from primary extranodal disease can be difficult.

Malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with extranodal localization occurs in 10–20% of cases and most commonly affects the gastrointestinal tract (44%), the upper airway (19%), and can reach the bone (8th %). central nervous system (5%) [1]. Spinal cord and spinal cord involvement is more commonly a late manifestation of systemic disease. Primary spinal involvement from hematological disease is rare, with a higher incidence in immunocompromised individuals [2].

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common lymphoma subtype, accounting for 30-35% of all NHL [2]. It is also the subtype of lymphoma that most commonly affects the cerebrospinal axis [2].

We describe a rare case of NHL whose presentation made diagnosis difficult.

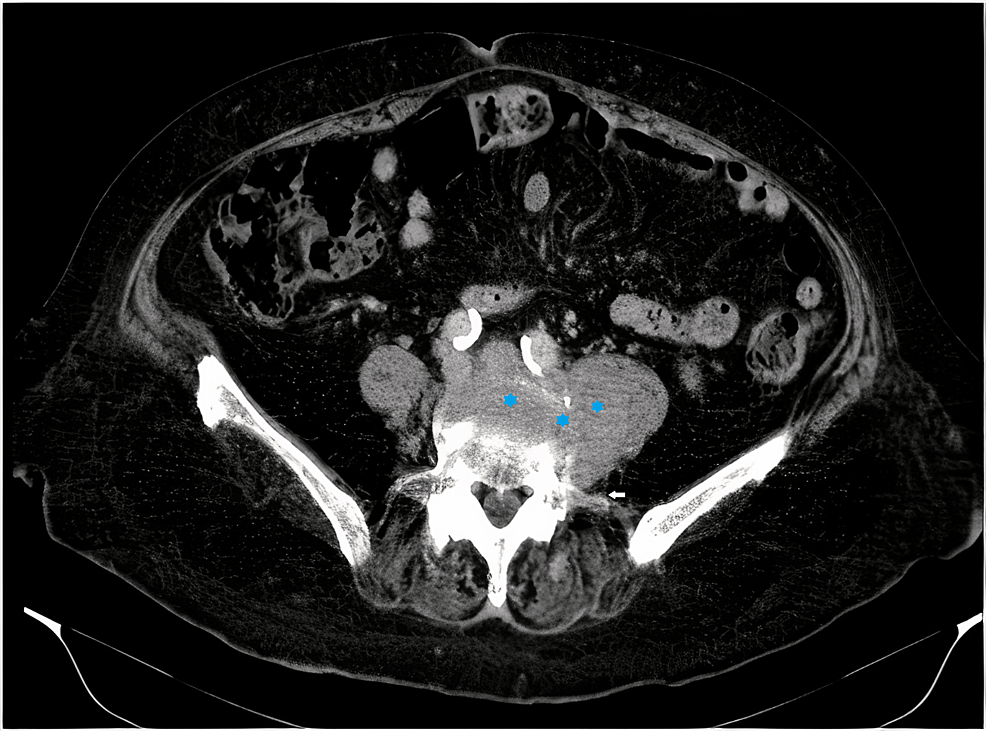

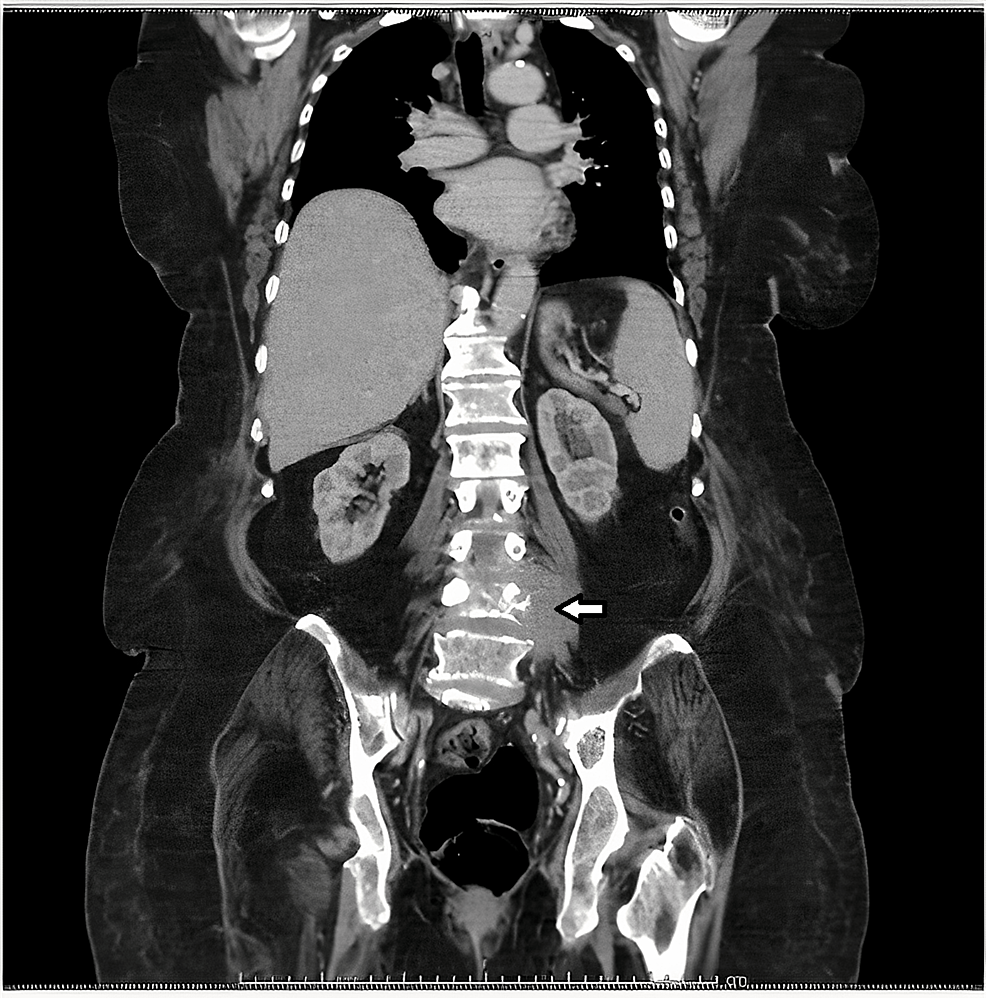

A 78-year-old woman presented to the hospital with complaints of severe pain in the lumbar region, hip, and left leg, evolving at 1 month, associated with asthenia and anorexia. She reported difficulty walking in the previous 2 months. The patient had a computed tomography (CT) scan of the lumbar spine performed outside the hospital showing a left paravertebral soft tissue mass infiltrating the vertebral body of the L4, L3-L4 and L4-L5 intersomatic spaces with intracanal extension and root compromise at this level , suggesting metastasis or an infectious lesion (Fig 1 and figure 2). She has been treated with opioid analgesics since the onset of the disease, but with ineffective pain control.

She had type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperuricemia, and major depressive disorder and was treated with sertraline 50 mg once daily (QD), furosemide 40 mg QD, pantoprazole 20 mg QD, amlodipine 5 mg QD, glargine insulin 16 U QD, linagliptin 5 mg QD, atorvastatin 20 mg treated QD, allopurinol 100 mg QD, gabapentin 200 mg QD and tapentadol 100 mg QD.

On physical examination, she was hemodynamically stable, subfebrile, and had a grade II/VI holosystolic murmur. She had a significant limitation in mobility of the lower extremities. Strength was reduced in both legs (grade 3/5) and sensation was reduced. The knee-to-shin maneuver was normal. The reflex was suppressed. The legs were hypotonic, but the mass was preserved.

The laboratory examination on admission showed leukocytes 10.8×103/uL, hemoglobin 12.7 g/dL, platelets 282×103/µL, ESR 70 mm/h, total protein 7 g/dL, albumin 3.5 g/dL, urea nitrogen 41.6 mg/dL, creatinine 1.3 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 91 mg/L and calcium 9 .9mg/dL. A proteingram was requested that showed no monoclonal peak, an immunoglobulin assay with no changes, and a serum protein immunofixation with no qualitative changes.

The hypothesis of spondylodiscitis was possible, so that the patient began antibiotic therapy with imipenem after taking a blood culture. The Infectious Diseases Service, considering the image compatible with spondylodiscitis, was asked to cooperate and it was decided to extend antibiotic therapy to 6 weeks. Despite the negative blood cultures, there was progressive clinical and analytical improvement (Tab 1).

On day 5 of hospitalization, a CT-guided biopsy of the lesion was performed without incident. A thoracoabdominopelvic CT scan was performed, which revealed no cervical, pulmonary, or abdominopelvic adenopathies.

On Day 20 of hospitalization, the anatomopathology report was available documenting “infiltration by a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoproliferative process of lineage B – non-Hodgkin’s B lymphoma, probably high grade/diffuse large cell.”

In the subsequent complementary diagnostic study, bone marrow examination and phenotyping, bone biopsy and urinary protein immunofixation showed no significant changes, and testing for hepatitis B and C and human immunodeficiency virus was negative. There was an increase in beta-2 microglobulin levels (13,720 µg/L; normal between 800-2,200 µg/L). Positron emission tomography (PET) was ordered, showing a single lesion with moderate uptake of the radiopharmaceutical fluorodeoxyglucose phosphorus 18 (FDG-18F), which is compatible with lymphoma with bone destruction at the L3 to L5 level. A definitive diagnosis of stage I primary extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was made.

A few days before the therapeutic decision-making consultation, the patient showed progressive clinical deterioration with loss of strength in the lower extremities and multiple nosocomial infections. The rapid deterioration of her general condition led to her death a few days later, despite the start of therapy (including steroids).

The diagnosis of extranodal NHL is challenging, particularly when the spine and cerebrospinal axis are involved, given the atypical presentation and the difficulty in obtaining a histological diagnosis. This localization is very rare and corresponds to 1–2% of extranodal lymphomas [2]. It usually occurs between the 5th and 6th decades of life in males (ratio 1.6:1). [2].

The most common symptoms are pain localized in the spine, often due to a pathological vertebral fracture, and later neurological symptoms. A small minority of patients experience B symptoms [2,3]. Spinal cord compression is typically associated with pain, paraesthesia, or paresis of the extremities [4].

To confirm primary extranodal lymphoma, a CT scan, MRI, and PET-CT should be performed [2]. Spinal MRI is one of the preferred imaging tests for assessing the spinal cord and delineating the extent of tumor invasion at the spinal space level [5]. PET is an essential imaging study for examining this type of lesion, particularly because large B-cell lymphoma has a high affinity for 18F-FDG [5]. Lesion biopsy is extremely useful for early diagnosis and ruling out other differential diagnoses.

Although the present case could not be initiated, treatment includes chemotherapy (CHOP or R-CHOP – rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) in conjunction with intrathecal chemotherapy [6]Radiation therapy, steroid therapy (for spinal cord compression or patients at risk for central nervous system progression), bone marrow transplantation, and surgery (to stabilize the spine or for refractory disease). [2,5,6]). The therapeutic approach for primary vertebral NHL is not well established given its rarity.

The prognosis of primary cervical lymphoma is poor, with variable survival rates, with some studies reporting a first-year survival rate of 10% [2]. Factors with poor prognosis are age over 50 years, more aggressive histologic types, and neurologic symptoms [7]Factors that were present in this case.

The importance of this case lies in the fact that it is an unusual form of presentation of NHL, but one that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of paraspinal or spinal masses. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to improve prognosis.

Disclosing rare clinical cases can help other colleagues in the differential diagnosis of pathologies that are difficult to diagnose. Although this case is rare, it can become a useful reminder that rare pathologies should not be forgotten during the diagnostic process.

#atypical #presentation #nonHodgkin #lymphoma

Leave a Comment