It is not every day that we learn something that fundamentally changes our understanding of our world. But for UC Santa Barbara earth scientist Matthew Jackson and thousands of volcanologists around the world, such a revelation has come.

While extracting magma from Iceland’s Fagradalsfjall volcano, Jackson and his collaborators discovered a far more dynamic process than anyone had anticipated in the two centuries that scientists have studied volcanoes.

“Just when I think we’re getting close to asking how these volcanoes work, we get a big surprise,” he said.

The geologists’ findings are published in the journal Nature.

10,000 years in one month

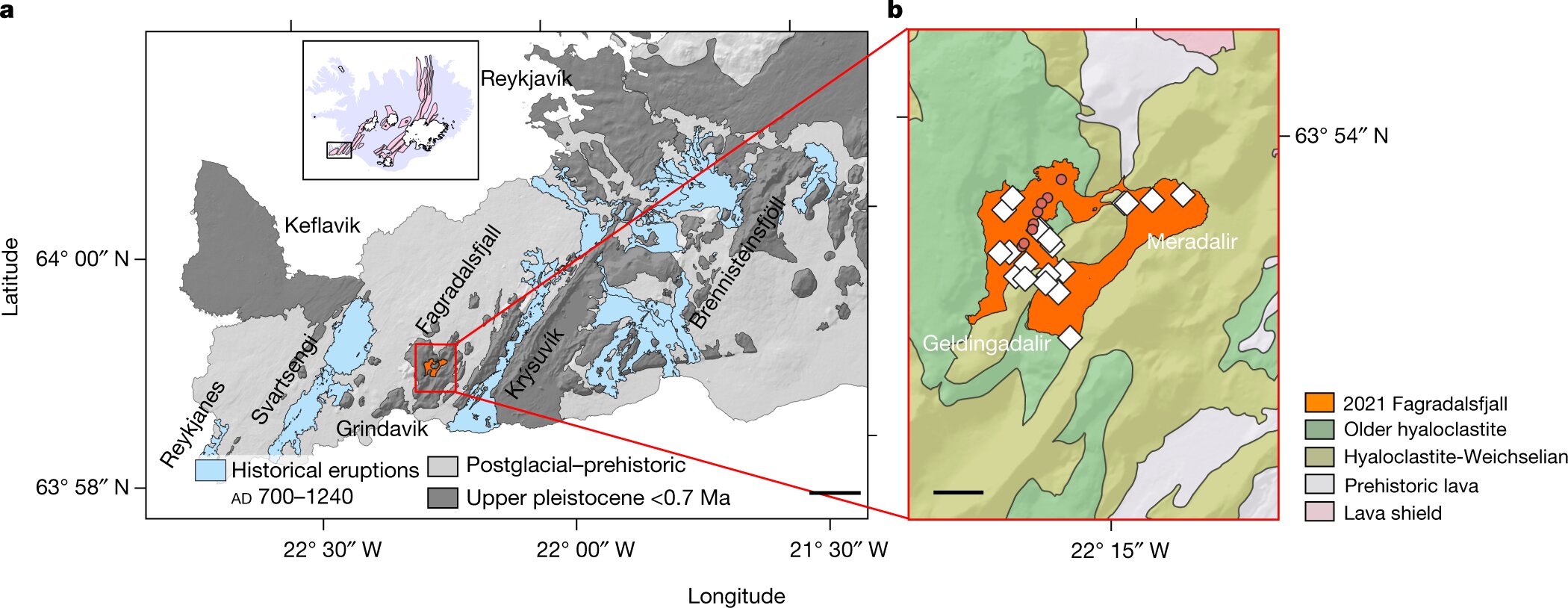

It took a sabbatical, a pandemic and 780 years of melting underground rock to put Jackson in the right place and time to witness the birth of Fagradalsfjall, a fissure in the lowlands of southwest Iceland that split in March 2021 and exploded with magma At the time, he said, everyone in the Reykjanes Peninsula was ready for some kind of eruption.

“The earthquake swarm was intense,” he said of the roughly 50,000 tremors — around magnitude 4 and higher — that shook the earth for weeks and kept most of Iceland’s population in suspense.

But the sleep deprivation paid off, and the weirdness turned to intrigue as lava rose and spurted out of the hole in the ground of the relatively empty Geldingadalur region. Scientists and visitors alike flocked to the area to see the latest section of Earth’s crust shape. Thanks to the winds that blew away the noxious gases and the slow flow of the lava, they were able to get close enough to sample the lava continuously right from the start.

What the geologists, led by Sæmundur Halldórsson of the University of Iceland, were trying to find out was “how deep in the mantle the magma formed, how far below the surface it was stored before the eruption, and both what happened before in the reservoir and during the eruption. “Questions like these, while fundamental, are actually some of the greatest challenges facing those who study volcanoes, due to the unpredictability of eruptions, the hazards and extreme conditions, and the remoteness and inaccessibility of many active sites.

“The assumption was that a magma chamber fills up slowly over time and the magma gets well mixed,” Jackson explained. “And then it empties as the eruption progresses.” As a result of this well-defined two-step process, he added, those who study volcanic eruptions don’t expect significant changes in the chemical composition of magma as it flows from the Earth.

“We see that at Mount Kīlauea in Hawaii,” he said. “You will have eruptions that last for years and there will be minor changes over time.

“But in Iceland, there were more than a factor of 1,000 higher rates of change for key chemical indicators,” Jackson continued. “In one month, the Fagradalsfjall eruption showed greater compositional variability than the Kīlauea eruptions in decades. The full range of chemical compositions sampled from this eruption over the course of the first month encompasses the full range that has ever erupted in southwest Iceland in the last 10,000 years.”

According to the scientists, this variability is the result of subsequent batches of magma pouring into the chamber from deeper layers.

“Imagine a lava lamp,” Jackson said. “You have a hot bulb at the bottom, it heats a blob and the blob rises, cools, then sinks. We can imagine Earth’s mantle — from the top of the core to below the tectonic plates — functioning much like a lava lamp.” When the heat causes regions of the mantle to rise and plume, forming and floating upward to the surface moving, he explains, molten rock from these plumes collects in chambers and crystallizes, gases escape through the crust, and pressure builds until the magma finds a way to escape.

As described in the publication, the expected “depleted” type of magma that had accumulated in the reservoir, located about 10 miles (16 km) below the surface, erupted in the first few weeks. But by April, evidence showed the chamber was being recharged by deeper, “enriched” melts of a different composition, originating from a different region of the rising mantle plume beneath Iceland. This new magma had a less altered chemical composition, with a higher magnesium content and higher proportion of carbon dioxide gas, indicating fewer gases had escaped from this deeper magma. By May, the magma that dominated the flow was the deeper, enriched type. These rapid, extreme changes in magma composition at a plume-fed hotspot “have never before been observed in near real time.”

These compositional changes may not be that rare, Jackson said; It’s just that opportunities to sample eruptions at such an early stage are not common. For example, prior to the eruption of Fagradalsfjall in 2021, the most recent eruptions on Iceland’s Reykjanes Peninsula occurred eight centuries ago. He suspects this new activity signals the start of a new, possibly centuries-long, volcanic cycle in southwest Iceland.

“We often don’t have records of the early stages of most eruptions because they get buried by lava flows from the later stages,” he said. This project, the researchers say, allowed them to see for the first time a phenomenon that was thought possible but had never been observed directly.

For the scientists, this result represents an “important limitation” on how models of volcanoes around the world are built, although it’s not yet clear how representative this phenomenon is of other volcanoes or what role it plays in triggering an eruption. For Jackson, it’s a reminder that the earth still has secrets to reveal.

“So when I go out to sample an ancient lava flow, or when I read or write articles in the future,” he said, “it will always come to mind: This may not be the full story of the eruption.”

Iceland’s volcanic eruption opens a rare window on the earth beneath our feet

Sæmundur A. Halldórsson et al., Rapid Displacement of a Deep Magmatic Source at Fagradalsfjall Volcano, Iceland, Nature (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04981-x

Provided by the University of California – Santa Barbara

Citation: Recent Icelandic Fagradalsfjall Eruption Findings Changing What We Know About How Volcanoes Work (2022 September 15) Retrieved September 16, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-09-iceland-fagradalsfjall -eruptions-volcanoes.html

This document is protected by copyright. Except for fair trade for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is for informational purposes only.

#results #Icelands #Fagradalsfjall #eruptions #changing #knowledge #volcanoes #work

Leave a Comment