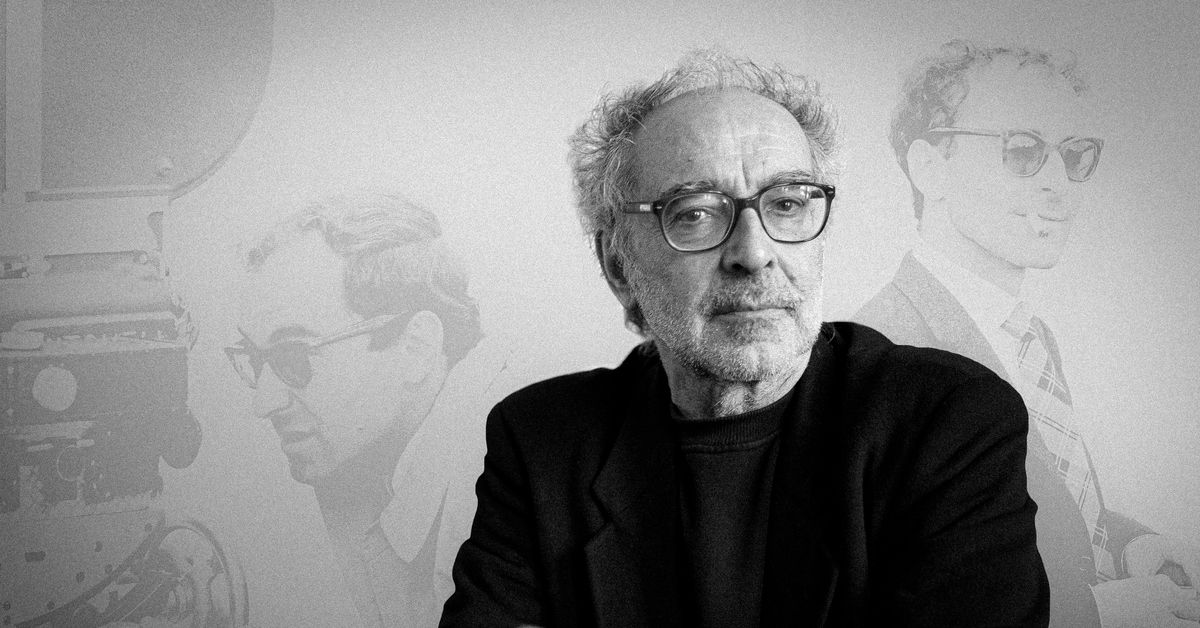

In a career that spanned nearly 60 years and spanned more than 40 feature films—a career that helped codify one of the most important formal movements in a medium’s history and exploded its potential for political commentary—Jean-Luc did Godard practically everything except make a film that’s two hours long. This habitual brevity could portray the Franco-Swiss filmmaker, who died Tuesday aged 91, as a shrewd, frugal master of history (he was) or a mischievous little boy who runs around until he tires (that, too) . But his bold mix of exuberance and composure ensured that Godard’s films, though copied and copied and copied, could never be reproduced in a way that would fool a viewer more than a few frames.

Godard was born in Paris in 1930, the son of a doctor and the heiress to an investment banking fortune. His childhood was interrupted by World War II and the rise of fascism in Europe; He and his family spent most of the war in Switzerland, returning only briefly to France. As a teenager, Godard wasn’t a movie obsessive, but more the kind of charismatic quasi-slacker who graced the upper class. He thought he could paint or write novels or become an anthropologist, but he was a disinterested student. By 1950, however, when he had more or less copied his classes at the Sorbonne, Godard had joined a group of young enthusiasts who would soon become France’s critical avant-garde, including the founders of The Totemist Cahiers du Cinema.

This cadre of critic-turned-filmmakers, which also included Francois Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette, became known as the French New Wave. The directors rejected what Truffaut described, with scathing, faint praise, as French cinema’s “quality tradition”: films that were stiff and literal, too desperate to be recognized as the literature or fine arts of the past. Instead, they advocated a new approach that took advantage of the medium’s unique abilities and made way for the intertextual innuendo, existential riffs and political charge that shaped their conversations with each other. Truffaut’s 1959 debut, The 400 beatswas in many ways the big bang of the movement, a film that makes youth seem both alienating and endless, ending with the main character staring straight at the audience.

Godard’s own debut the following year, Breathless, follows a young man who kills a police officer before hiding with an unwitting lover – an American transplant. The man is obsessed with Humphrey Bogart, and while he lives through the most despicable and harrowing situations a young Frenchman could be going through right now, they’re all filtered through a pop culture affect where every move, every tic is confidently learned. (Breathless seems to be arguing: Isn’t that the case for all of us anyway?) The viewer doesn’t have to strain to find the neurotic self-examination in a film whose first line translates to “After all, I’m an asshole.”

Leaving aside the postmodern bleeding of imagism into instinct, Breathless became known for his great technical innovation, the use of jump cuts. Aside from its obvious practical advantages (time saving, moving plot), the technique has the effect of making a character’s movement between moments of moral conundrum both urgent and random. It also makes clear the director’s presence over what is happening on screen. Making the tension between this haunting admonition and the documentary style of photography and lighting Breathless One of the most unique films of the 20th century, hyperreal and fantastic at the same time.

Several of Godard’s early masterpieces, including the 1961s A woman is a woman– where a character was played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, who had played the lead role BreathlessHe says he wants to watch a TV show from Breathless– Star of his first wife, actress Anna Karina. Through Karina, Godard learned the power a movie star’s charisma has over an audience and the power a filmmaker can gain by holding them back. In the 1962s Vivre sa viewhere Karina’s Nana resorts to sex work after leaving her husband and young child to pursue a film career, she and her ex-husband speak for more than eight and a half minutes before both of their faces are caught in anything other than a dim cafe mirror you can see .

Godard’s keenness to capture the roar in young people’s minds was not limited to exploring their cinematic interests. Towards the end of the 1960s he began making explicitly political films, although these too existed in a world stifled by commercial entertainment. An intertitle in the 1966s Masculine Feminine refers to characters as “The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola”. In 1968 he and Truffaut protested at the Cannes Film Festival on the grounds that the films shown there were not in solidarity with the workers. A decade later, after being commissioned by the Mozambique government to direct a short film, he chided Kodak for the inability of its footage to capture the nuances of dark skin.

In a catalog that includes musical comedies and lopsided, non-real Shakespearean adaptations — 3-D larks about dogs that translate couples’ arguments and experiments into digital handheld photography — Godard’s personal restlessness is never far out of bounds.

Godard is one of the most cited characters in film. You are probably also familiar with many of his maxims without attributing them to him: “A film has a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order”; “Every edit is a lie”; “Photography is truth – cinema is truth 24 times a second”; “Art is not a reflection of reality, it is the reality of a reflection”; “All it takes to make a movie is a girl and a gun.” The last is undoubtedly his most repeated and seems to have been embraced by studio execs around the world as untouchable marketing wisdom. But Godard credited it to American director DW Griffith; he just borrowed it. For an artist whose work was so gleefully intertextual, it is fitting that Godard’s most famous piece of advice was stolen from someone whose techniques he falsified and whose politics he certainly despised.

After news of his death broke in the press on Tuesday, another quote from Godard began circulating online, one that stood out not for its cleanliness but for its deference. In a 1983 interview with movie quarterlyhe said:

I find it pointless to keep offering the “authors” to the public. When I received the Golden Lion award in Venice, I said that I probably only deserve that lion’s mane and maybe the tail. Anything in the middle should go to everyone else working on a picture: paws to the cameraman, face to the editor, body to the actors. I don’t believe in the loneliness of an artist and the author with a capital “A”. … In general, today there is a tendency to look at the director’s problems without thinking that there are many other characters behind him who are just as important in the making of the film.

He was right about the work that actors and crew members put into film production and the creative consequences their work can have. But few filmmakers have done more to advance the idea of auteur film or to argue for its worth. In Godard’s work, authorship is both inescapable – in the way he broke the routine of old cinema to embrace an emotional one – and philosophically strained, as a thousand concerns and references fend off even the simplest stories.

Godard died at his home in Rolle, Switzerland, on the north shore of Lake Geneva, where he had reportedly undergone assisted suicide procedures permitted under Swiss law. His lawyer said The New York Times that Godard suffered from “several disabling pathologies,” while a family member told several newspapers he was “not ill — he was just exhausted.” (In the perhaps more telling, if equally cryptic quote, the attorney said to the Times that his client “couldn’t live like you and I did”.) He kept the tiredness that set in until he was ten decades away from his work. His last release, 2018 The picture bookis a prismatic essay film that argues, at least from some angles, that Western cinema has calcified reduced narratives about the rest of the world, particularly the Middle East, while ignoring much of its own history.

Largely an act of collage, The picture book mutates parts of other films – some famous, some from Godard’s own – to a degree that many are almost unrecognizable and most feel entirely new. Without the help of actors or a script, the author’s hand reaches through the story to take the familiar in a new rhythm to new purposes.

Paul Thompson is a Los Angeles-based author. His work has appeared in Rolling Stone, new York magazine and GQ.

#JeanLuc #Godard #egoless #author

Leave a Comment