(opens in new tab)

Underwater robots peering beneath Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier, also dubbed the “Doomsday Glacier,” saw that its sinking could come sooner than expected with an extreme spike in ice loss. A detailed map of the seafloor around the icy behemoth has shown that the glacier has undergone periods of rapid retreat over the past few centuries, which could be triggered again by a melt it drives climate change.

Thwaites Glacier is a huge chunk of ice – about the size of the state of Florida in the US or the entire UK – that is slowly melting in the ocean off West Antarctic. The glacier gets its ominous nickname because of the “scary” implications of its complete liquidation, which could raise global sea levels between 3 and 10 feet (0.9 and 3 meters). Researchers said in a statement. Due to climate change, the vast frozen mass is retreating twice as fast as it was 30 years ago, losing about 50 billion metric tons (45 billion metric tons) of ice annually International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration.

Thwaites Glacier extends well below the sea’s surface and is held in place by jagged points on the sea floor that slow the glacier’s slide into the water. Sections of seafloor that capture the underbelly of a glacier are called “ground points” and play a key role in how quickly a glacier can retreat.

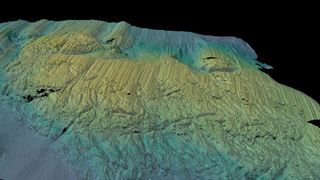

In the new study, an international team of researchers used an underwater robot to map one of Thwaites’ previous grounding points: a prominent seafloor ridge known as “The Bump,” located about 650m below the surface. The resulting map showed that sometime during the past two centuries, when the uplift was supporting Thwaites Glacier, the glacier’s ice mass was retreating more than twice as fast as it is today.

Related: The “doomsday glacier” in Antarctica could face its demise within 3 years

Researchers say the new map is like a ‘crystal ball’, showing us what could happen to the glacier in the future if it breaks away from its current grounding point – which is about 300m below the surface – and is anchored to a deeper one like the bump. That scenario could become more likely in the future as increasingly warmer water melts away the glacier’s guts, the statement said.

“Thwaites is really holding on to his fingernails today,” study co-author Robert Larter, a marine geophysicist with the British Antarctic Survey, said in the statement. “We should expect big changes in small periods in the future.”

Read between the lines

The researchers mapped the bump using the underwater robot Rán (named after the Norse goddess of the sea), which spent about 20 hours scanning a 5-square-mile (13-square-kilometer) section of the former ground point.

The resulting map showed that the bump is covered with about 160 parallel ridge lines, giving it a barcode-like appearance. Also known as ridges, these odd-looking grooves are between 0.3 and 2.3 feet (0.1 to 0.7 m) deep. The spaces between the ribs are short and wide, ranging from 1.6 to 10.5 m (5.2 to 34.4 ft) apart, but most commonly they are about 7 m (23 ft) apart.

These ridges are actually imprints left when the tide briefly lifted the glacier off the sea floor, pushing the ice mass slightly further inland before the ebb tide lowered it back down. Each rib represents a single day; Together, the lines depict the gradual movement of the glacier over a period of about 5.5 months. The different depths and distances between the ribs correspond to the cycle of spring and neap tides, during which the glacier moves further and with greater force. (During spring tide, the tide is higher and the tide is lower. During the neap tide, the tide is lower and the tide is higher.)

(opens in new tab)

“It’s like looking at a tide gauge on the sea floor,” the study’s lead researcher Alastair Graham, a geological oceanographer at the University of South Florida, said in the statement. “I’m really blown away by how beautiful the data is.” However, the noticeable ridges on the seabed are also a concern, he added.

Based on the spacing of the ribs, the researchers estimated that the icy mass was retreating at a rate of 1.3 to 1.4 miles (2.1 to 2.3 km) per year when Thwaites Glacier was anchored at the elevation. That means the glacier was retreating almost three times faster than between 2011 and 2019, when it was retreating at a rate of about 0.8 km per year, according to satellite data.

Related: Alarming heat waves hit the Arctic and Antarctic simultaneously

Researchers aren’t sure exactly when the glacier sat on the ridge, but it was definitely within the last two centuries and most likely sometime before the 1950s. The team was unable to collect the necessary seafloor core samples to properly age the survey, as increasingly icy conditions around the glacier meant they, too, said they had to quickly withdraw from the region. However, the team intends to return soon to properly answer this important question.

(opens in new tab)

The new results are worrying because they show that Thwaites Glacier experienced “pulses of very rapid retreat” even before the effects of climate change increased the current rate of ice loss, Graham said. It shows that the glacier has the potential to accelerate much faster if it breaks away from its current grounding point and anchors at a subsequent hump-like grounding point, he added.

Previous research with robotic submarines has shown that surprisingly warm water under the glacier could melt the underbelly of the icy mass, which could rapidly propel the glacier toward this turning point.

“Once the glacier retreats beyond that [the current] flat ridge in its bed,” Larter said, saying it could only be a few years before a similar rate of withdrawal is reached at the age of the bump.

The study was published online Monday (September 5) in the journal nature geosciences (opens in new tab).

Originally published on Live Science.

#Doomsday #Glacier #teetering #closer #catastrophe #scientists #thought #seafloor #map #shows

Leave a Comment