When Miki Boleen sees new parents in her doctor’s office, she often asks if they have vaccinated their child against polio, a disease that has left her immobilized.

She doesn’t want to scare, but as vaccination rates among babies and young children plummet due to missed routine shots early in the pandemic, she hopes her story will help others stay healthy. Boleen, 83, suggests people speak to their doctor — and others who have had infectious diseases that can be prevented with vaccines.

Her message is simple: Why not consider vaccination and prevent a preventable serious illness?

“Please, please get your children vaccinated,” the Abbotsford, BC resident said in a conversation with Dr. Brian Goldman, the presenter of CBC Radio White coat, black art. “You don’t want them to end up like me.”

As these talks come about, public health experts are warning that polio could resurface after outbreaks in the US and UK new York This summer, a young man became paralyzed after contracting polio, the first case in the United States in nearly a decade. health authorities are investigate how the disease is linked to virus detections in England and Israel.

In the 1990s, polio was largely eradicated here through mass vaccination campaigns that began in Canada in 1955. Previously, thousands of children were infected.

Boleen first had polio when she was eight years old in Gladstone, Man., about 100 miles west of Winnipeg. The only negative effect at first was that I could no longer run fast.

Then, over time, Boleen was reinfected by another strain 1953 epidemic. Winnipeg has been the epicenter, with more than 2,300 cases out of nearly 9,000 in the country – including 500 deaths this year.

Headaches became an ambulance ride for the then 14-year-old when she could no longer walk, coupled with fears she might die.

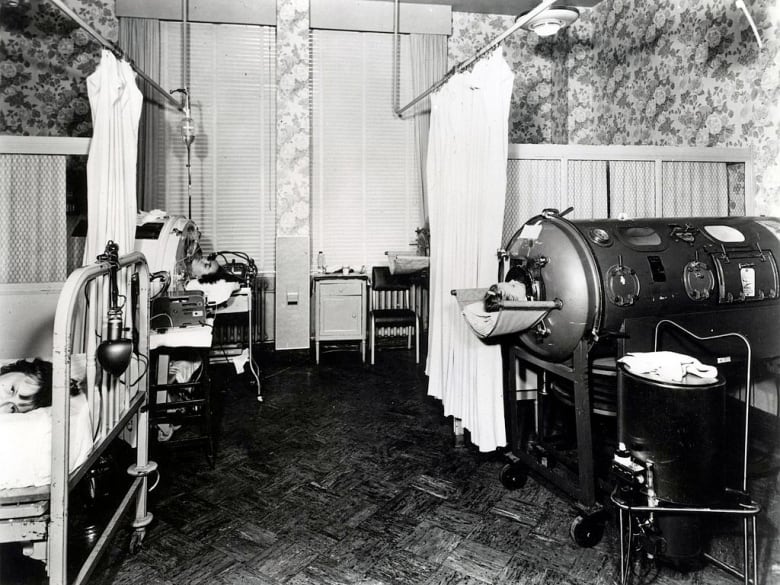

In the hospital’s children’s ward, others with polio lay in the beds next to her. All of the beds were pushed together so tightly that if the children had been able to move at that point, they could have rolled onto another bed, she said.

“Sometimes I would hear noises at night and wake up,” Boleen recalled. “Well I couldn’t move and my voice was just a whisper at the time but I knew what was going on. I either heard a ventilator fail during the night or saw staff come in and take someone out of the bed next to me. And you knew they had died.”

In the morning, the children were told that the patient had been transferred. As the eldest on the ward, Boleen knew what really happened.

She says she is still traumatized by the deaths she witnessed.

Polio can strike again

Boleen was in hospital for nine months, followed by surgeries and a full leg brace to help her walk again.

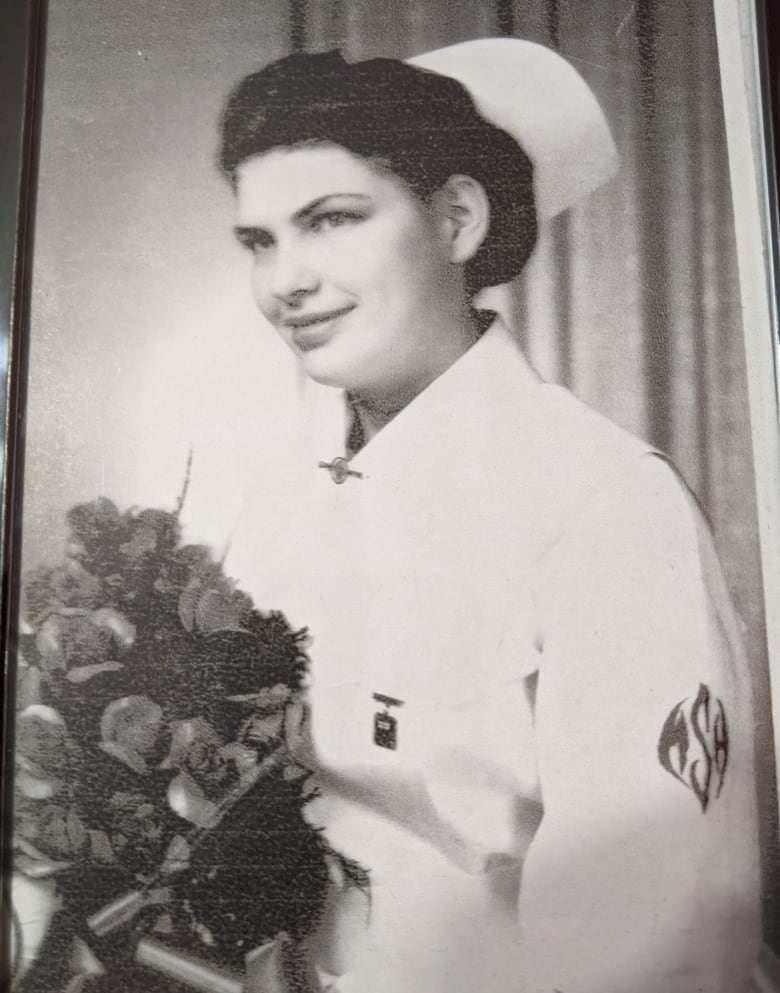

She threw away the braces and crutches before beginning training as a psychiatric nurse at 16. Despite loving her career, symptoms of post-polio syndrome emerged in 1986 and she retired early.

White Coat Black Item no26:30Polio comeback threatens Canadians

Polio is making a comeback around the world, and falling immunization rates in Canada are leaving us vulnerable to a disease that was once on the brink of eradication. Miki Boleen, an 83-year-old polio survivor, has taken it upon herself to urge parents to get their infants vaccinated as rates of routine vaccinations plummet.

Learning from this summer’s case of crippling polio in an adult in new York The state angered Boleen, she said, but expected it due to falling vaccination rates. About 40 percent of two-year-olds were not up to date with their vaccines in their area of BC

Canada’s polio immunization goal is 90 percent, but multiple provinces and territories fall below that goal, including 88 percent in BC and 86 percent in Manitoba.

Decline in immunization must be reversed: public health

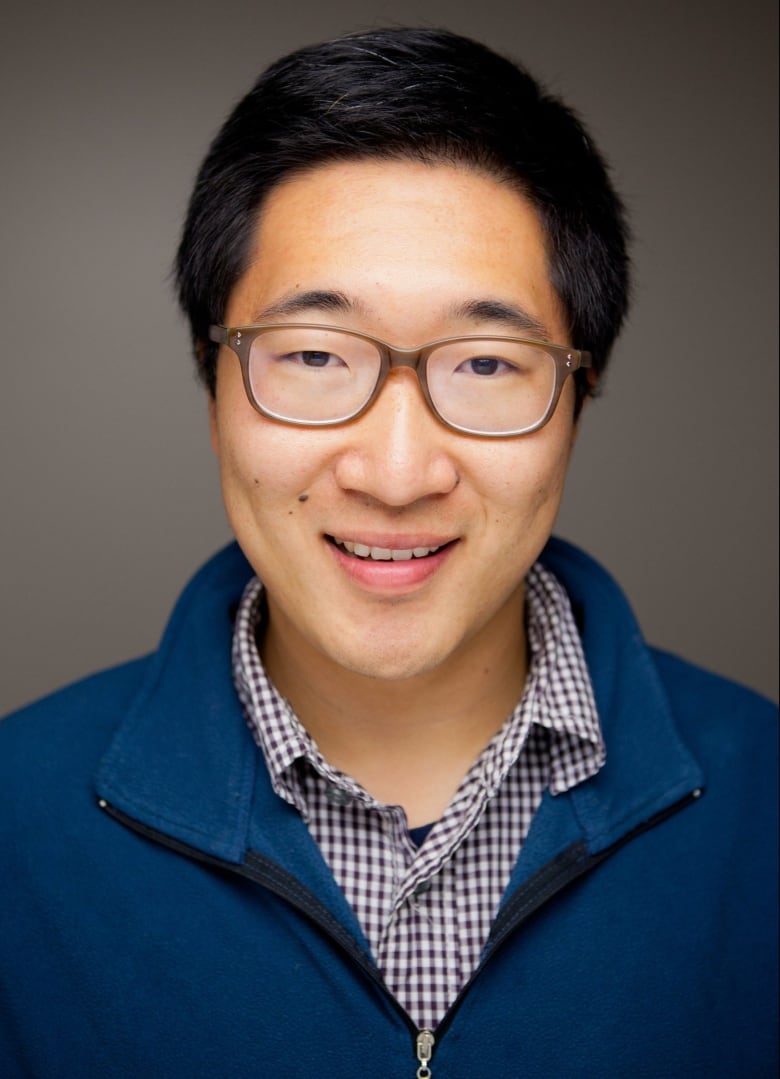

dr Jia Hu is CEO of 19 To Zero, a nonprofit coalition of medical and other experts facilitating vaccination. Her efforts include campaigns targeting parents of babies and preschoolers who missed polio and other shots when primary care offices were closed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hu’s team conducted a series of surveys that indicated this vaccination protection dropped from 70 percent to less than 1 percent in school-age children who received the HPV vaccine, which protects against cancer that still kills about 400 Canadians each year.

Vaccination for babies and preschoolers, which protect against polio and measles, saw a decline of about 25 percent, said Hu, who is also a public health specialist and family doctor. Before the pandemic, a five percent drop would be considered massive and worrying, he noted.

“The main reason for all of these declines has actually been limited access,” Hu said, particularly to GPs and nurses during the pandemic.

“There is a total crisis in basic services,” Hu said. “What we need is a primary care that is supported in the provision of vaccinations.”

The all-hands-on-deck approach to keeping Canadians up to date on their vaccinations should include pharmacists, just as they have helped roll out COVID-19 vaccines to adults, he said, as well as online Registers that allow parents to report when their children need a top-up.

understanding and reach

Hu was the health officer during a Covid-19 outbreak at a Cargill meat processing plant in High River, Alta, where his team helped run town halls, translate materials, and set up immunization clinics where community leaders encouraged residents to turn up.

“We started a pretty big vaccination campaign in rural northern Alberta,” Hu recalled.

To succeed, Hu said they used surveys and focus groups to understand why COVID-19 vaccination rates among rural residents lagged behind urban residents, followed by TV ads, billboards and social media campaigns. A similar reach could also routinely increase other types of vaccination rates, he said.

dr Zulfiqar Bhutta, Chair for global child policy at the Center for Global Child Health at Sick Kids in Toronto, also says understanding what is driving a community’s concerns about vaccination is key to promoting acceptance. He works in two countries where wild poliovirus is still circulating: Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Bhutta said polio will not be eradicated until it is under control around the world. To promote vaccinations in Pakistan, Bhutta speaks to parents about their family’s unmet needs, such as hunger and reproductive care. The team is working to offer these services alongside vaccines.

Public health doctors and nurses often say that vaccines are a victim of their own success because we don’t see the diseases and deaths they averted. But they only work if enough population gets the protection.

“I often tell people what we see in lower-middle-income countries, we see in high-income countries in niches of deprivation,” said Bhutta, who also works at the Institute for Global Health and Development at Aga Khan University in Karachi, Pakistan, operates.

Bhutta said vaccine hesitancy can be mitigated everywhere by reaching out to the most vulnerable and maximizing participation.

In Canada, Boleen brings her disappointment at declining vaccination rates to her speeches in support of the March of Dimes’ work Post-Polio Survivorsand conversations to help younger adults discover just how harmful polio can be.

“Believe me, if I could have gotten the vaccine, I wouldn’t have had polio twice and I’d still be dancing,” Boleen said. “That’s what I miss the most.”

#womans #pitch #parents #aims #avert #polio #resurgence #CBC #radio

Leave a Comment