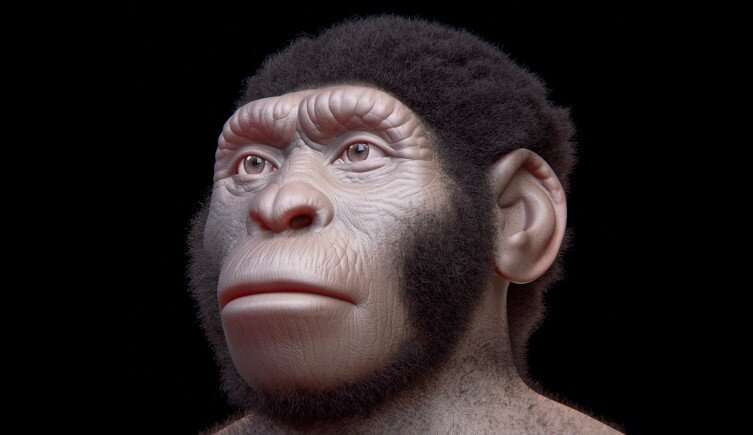

From Homo erectus to more modern species, sinuses can help reveal changes within the ancient human species. Credit: Rick Neves/Shutterstock

The changing shape of the frontal sinuses helps reveal more about how modern humans and our ancient relatives evolved.

An international team of researchers led by Antoine Balzeau of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle revealed that the small cavities located just above the nose are related to the size of the frontal lobe.

This part of the brain is responsible for processes that make us uniquely human, like language, emotions and planning, and the sinuses now offer scientists another way to infer the development of this part of the brain.

The frontal sinuses also provide a new way to study relationships between different species of ancient hominins, with the study providing additional support for Homo naledi, which belongs to our genus despite sharing some pre-human characteristics.

Professor Chris Stringer, an expert on human evolution at the museum who co-authored the paper, says: “Sinuses are interesting morphological features in fossils, but they have been neglected. Many papers describing new species do not mention them, and they are often only figured incidentally with the rest of the specimen.”

“This has caused the data to vary widely. To correct this, this paper has compiled the largest selection of fossil sinus data of all time from many different sources.

co-author dr. Laura Buck, a former staff member at the museum but now at Liverpool John Moores University, adds: “In early hominins and nonhuman apes, the size and shape of the frontal sinuses are directly related to the space available for them to grow into.”

“The gradual change we see between these species and later hominins, including ourselves, suggests a shift in the way the skull is organized and evolved. It may be relevant that this is happening at the same time that we are beginning to see significant brain expansion in these taxa.”

The results of the study were published in the journal scientific advances.

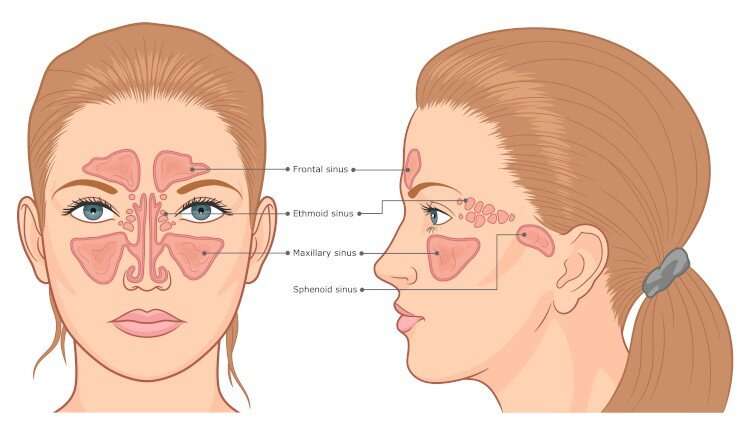

Our species, Homo sapiens, has four types of sinuses – two of which are unique to humans and our close relatives. Credit: Refluo/Shutterstock

What are sinuses?

Sinuses are air-filled spaces within the bones of the skull that are lined with a mucous membrane. Humans have four types of sinuses: the maxillary sinuses under the eyes, the ethmoid sinuses between the eyes and nose, the sphenoid sinuses on the outside of the eyes, and the frontal sinuses.

Although they have been known for centuries, their role is unclear. Suggestions that they produce mucus and nitric oxide to protect themselves from infection, or provide heat and shock protection to the nervous system may help explain their current function, but not necessarily why they evolved.

Some researchers have even suggested that sinuses are an example of an evolutionary spandrel, a structure that evolved as a byproduct of something else and played no original role. Another adaptation may give it a function later in evolutionary time.

Research on other animals, such as cattle and primates, has shown that the sinuses can differ between species, raising interest as to whether the sinuses might also be helpful in distinguishing between ancient human species.

The exact path of human evolution is still the subject of heated debate, with many competing theories about how our species came about and how many close relatives we have. Studying the sinuses of ancient species could help fix this.

Of particular interest are the maxillary and frontal sinuses, as in primates they are found only in humans and our closest relatives, the chimpanzee and gorilla.

This new study examined 94 fossil hominins from over 20 species to gain better insight into frontal sinus variation and what this tells us about human evolution.

How can sinuses be used to study human evolution?

The researchers used CT scans of the specimens to create 3D models of the frontal sinuses, which allowed them to digitally reconstruct the structures. These models were then used to make measurements that could be compared between the different species.

Your sinuses reinforce the classification of Homo naledi as an ancient human species. Image credit: Cicero Moraes (Arc-Team) et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

While the sinus size has not been able to distinguish between early species of hominins like Australopithecus, it has been able to separate newer homo species over the past two million years.

The study found that species like Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens have different ranges of sinus size, which the researchers think could be related to evolutionary limitations caused by the evolution of traits like larger brains.

This relationship has also been observed for Middle Pleistocene (770,000 to 120,000 years ago) hominins whose identity is currently uncertain, including in specimens associated with the controversial species Homo rhodesiensis.

“Three skulls that I believe represent Homo rhodesiensis are very different from the others,” says Chris. “Their sinuses are much larger than their relatives and we don’t know why. It could mean they are a specialized group.

“They have very large brow crests, which have been suggested to play a role in social signaling, and large sinuses would reduce the weight of these.”

Meanwhile, the sinuses of Homo naledi, whose mix of non-human and human traits has puzzled scientists, resembled those of Homo erectus. This supports the human status of H. naledi and adds more information that could help unravel its evolutionary past.

The study also reveals new information about our own evolution, indicating connections between these sinuses and the size of the frontal lobe of Homo erectus. The size of the sinuses is consistent with the development of a short elongation of one of the brain lobes relative to the other, a trait most people have today that can be associated with the dominant hand.

The researchers hope that future studies of ancient human fossils will map the sinuses to better understand the evolution of this trait and potentially provide new insights into the origins of our species and close relatives.

“After reading this paper, we hope more researchers will recognize the importance of the paranasal sinuses and start using them when describing or redefining a species,” says Chris. “As more data becomes available, it will help us better understand our development and the role that the sinuses play.”

Paleontologists unveil new data on the evolution of the hominid skull

Antoine Balzeau et al, Frontal sinuses and human evolution, scientific advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abp9767

Provided by the Natural History Museum

Citation: Sinuses Offer New Opportunities to Study Ancient Human Evolution (October 24, 2022) Retrieved October 24, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-10-sinuses-evolution-ancient-humans.html

This document is protected by copyright. Except for fair trade for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is for informational purposes only.

#Sinuses #offer #study #evolution #ancient #humans

Leave a Comment