If evolutionary biologist Terence D. Capellini were to rank the body parts that make us essentially human, the pelvis would be at the top.

Finally, its design allows humans to walk upright on two legs (unlike our primate cousins), and it allows mothers to give birth to babies with big heads (meaning big brains). At an anatomical level, the pelvis is well understood, but that knowledge begins to crumble when it comes to how and when this all-important structure takes shape during development.

A new study from Capellini’s lab is changing that. Published in scientific advances, the work shows when the pelvis takes shape during pregnancy and identifies the genes and genetic sequences that orchestrate the process. The work may one day shed light on the genetic origin of bipedalism and open the door to treatments or predictors of hip joint diseases such as hip dysplasia and hip osteoarthritis.

“This paper really focuses on what all humans have in common, which is these pelvic changes that allowed us to walk on two legs and give birth to a large fetal head,” said Capellini, a newly hired professor of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology and senior author of the study.

The study shows that many of the traits essential to human walking and childbirth form around the 6 to 8 week mark during gestation. These include key features of the pelvis that are unique to humans, such as its curved and basin-like shape. Formation occurs while the bones are still cartilage, allowing them to bend, twist, stretch, and grow easily.

The researchers also saw that when other cartilage in the body begins to transform into bone, this developing section of the pelvis stays as cartilage longer, giving it time to form properly.

“There seems to be a stall, and that stall keeps the cartilage growing, which was quite interesting and surprising,” Capellini said. “I call it a safe zone.”

Researchers performed RNA sequencing to show which genes in the region are actively triggering pelvic formation and halting ossification, which normally converts softer cartilage into hard bone. They identified hundreds of genes that are either turned on or off during the 6 to 8 week mark to form the ilium in the pelvis, the largest and top bone of the hip with blade-like structures that curve and form a pelvis rotate support when walking on two legs.

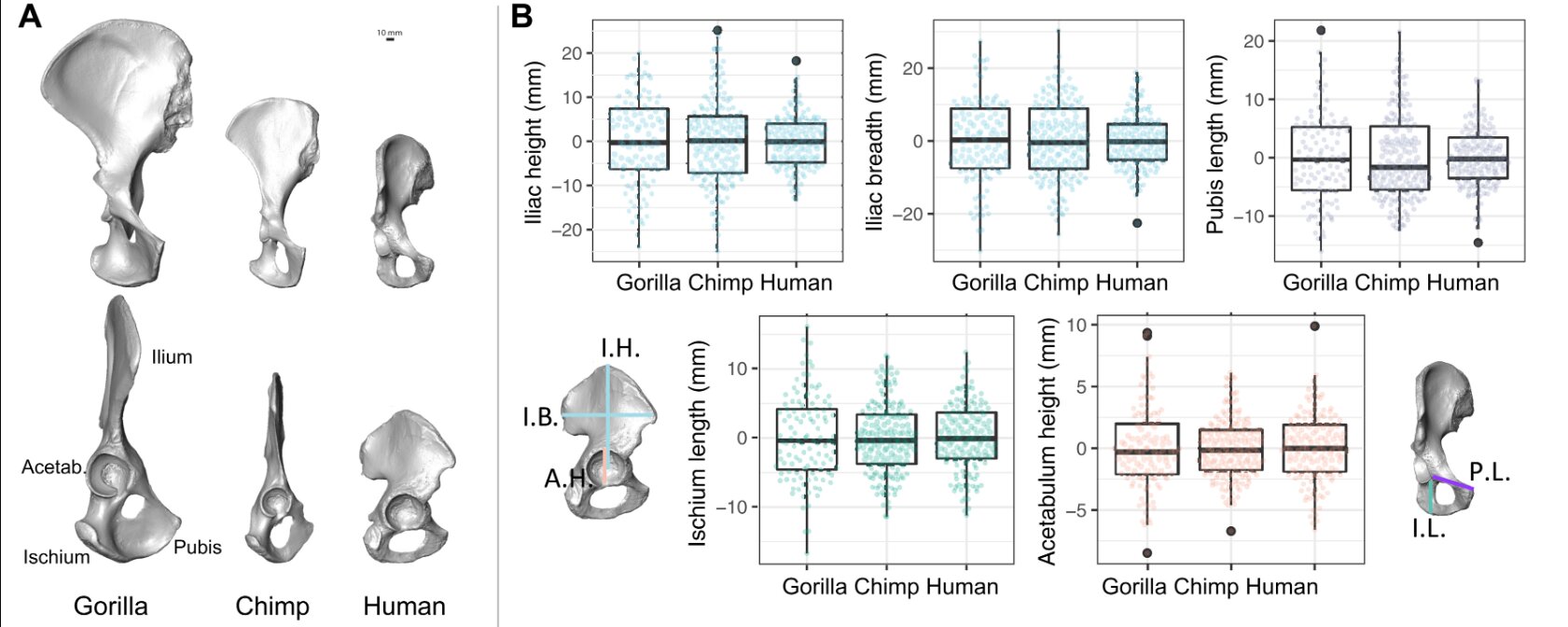

Compared to chimpanzees and gorillas, the shorter and wider realignment of our pelvic blades means humans don’t need to shift the bulk of our weight forward and can use our ankles more comfortably for walking or balancing. It also helps enlarge the birth canal. Great apes, on the other hand, have much narrower birth canals and longer iliac bones.

The researchers began the study by comparing these differences in hundreds of skeletal samples from humans, chimpanzees and gorillas. The comparisons showed the remarkable effects that natural selection had on the human pelvis, particularly the ilium.

To see when the iliac and pelvic elements that make up the birth canal began to take shape, the researchers examined 4 to 12-week-old embryos under the microscope with the consent of people who had legally terminated their pregnancies. The researchers then compared samples from the developing human pelvis to mouse models to identify the on and off switches that trigger the formation.

The work was led by Mariel Young, a former graduate student in Capellini’s lab, who will graduate in 2021 with her Ph.D. The study was a collaboration between Capellini’s lab and 11 other labs in the US and around the world. Ultimately, the group wants to see what these changes mean for common hip disorders.

“Walking on two legs affected our pelvic shape, which later affects our disease risk,” Capellini said. “We want to uncover this mechanism. Why does pelvic selection affect our later risk of hip disease, such as osteoarthritis or dysplasia? Making these connections at the molecular level will be crucial.”

Where do the gender differences in the human pelvis come from?

Mariel Young et al, The developmental impact of natural selection on human pelvic morphology, scientific advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq4884

Provided by Harvard University

Citation: Why do people walk upright? The secret is in our pelvis (2022, September 12), retrieved September 12, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-09-humans-upright-secret-pelvis.html

This document is protected by copyright. Except for fair trade for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is for informational purposes only.

#people #walk #upright #secret #pelvis

Leave a Comment