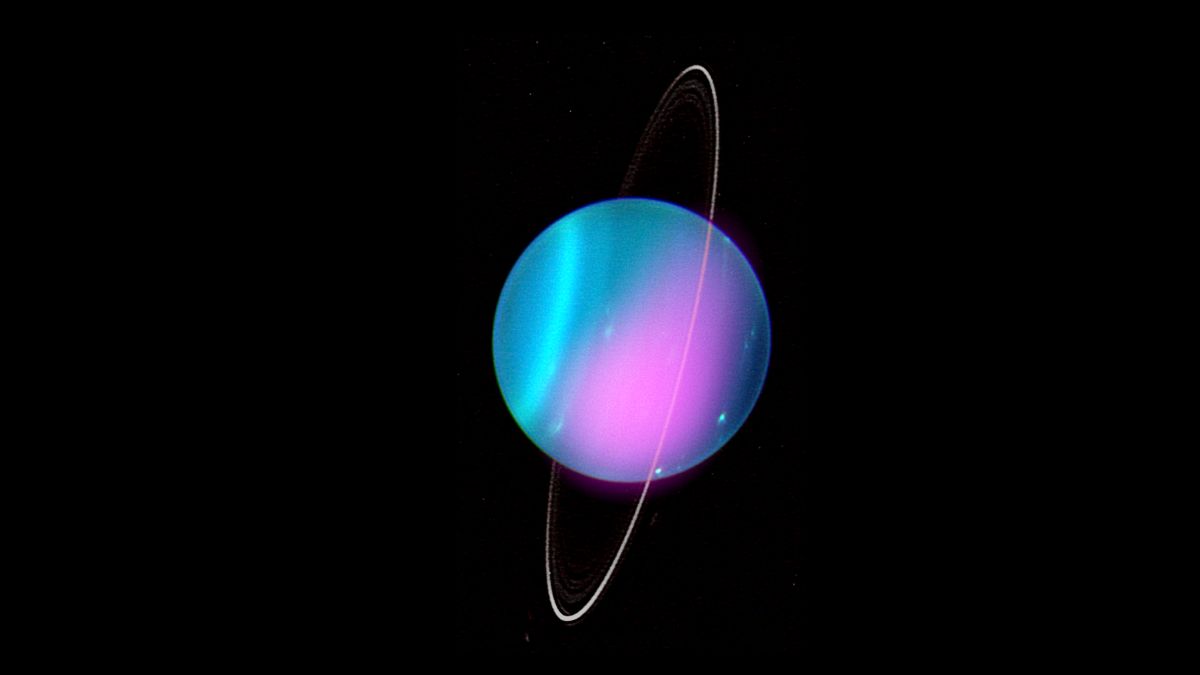

Uranus is just weird, and one of the weirdest things about it is its tilt.

Uranus has the greatest tilt in the Solar System at 98 degrees, meaning it rotates almost perfectly perpendicular to the direction of its orbit. Astronomers have long suspected that a series of giant impacts early in planet formation knocked Uranus on its side, but new research suggests a much less violent cause: a wandering Uranus satellite.

All planets of solar system Have orbital inclinations less than 30 degrees – except Uranus. The entire Uranus system is turned on its side, affecting not only the planet’s rotation, but also its rings and moons, which orbit the planet perpendicular to the planet’s motion Sun.

Related: Photos of Uranus, the tilted giant planet

The strange tilt of Uranus is particularly strange considering that the neighboring ice giant, Neptune, has a normal slope, although the two likely share similar formation histories. So what went wrong with Uranus?

Astronomers have long suspected that at least one giant impact took place as Uranus formed. It’s easy to imagine: the right collision at the right time would provide enough energy to knock Uranus over while it was still in its protoplanetary stage, and the planet never rose again before forming its system of planets and moons.

And scientists have some evidence to support this picture. The solar system was a pretty violent place when it was young, so there are a lot of big rocks that can wreak havoc. And Neptune has slight differences, such as B. a different temperature and a set of moons with different properties (like that Neptune is much larger), suggesting that the two planets had different conditions at some point in their formation.

The unhappiest planet

But the impact hypothesis also has weaknesses.

There wasn’t just one big rock whizzing through the early solar system looking for an unfortunate target – there were many. All planets, especially the outer ones, probably suffered many collisions during their formation. Even the inner planets were not spared; Earth was struck early on by a Mars-sized protoplanet that formed the Moon.

So if Uranus was hit hard enough to tip it over, why not the other planets? Jupiter and Saturn Eventually, thick clouds of gas developed that could have straightened them out over time. But Neptune had a history similar to Uranus, and despite their slight differences, the two ice giants are very similar: They have similar atmospheres, both have intricate magnetic fields, and both have similar sizes, masses, and rotation rates.

We are faced with a dilemma. Perhaps poor Uranus was just extremely unlucky – and there are simulations to support the idea that just the right impact will tip the world over. But “pure luck” doesn’t really satisfy the typical astronomer; we should exhaust all other options before resorting to it.

So maybe the answer has nothing to do with impact. Perhaps it has to do with moons, a team of scientists suggest in a new paper accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics published on the preprint site arXiv.org.

lost children

The early solar system did not look very much like today’s solar system. The giant planets in particular are likely to have formed much closer together and much closer to the Sun. Over time, interactions occur between them and with outwardly migrating planetesimals, with Uranus and Neptune migrating furthest. (In fact, some solar system models even predict the existence of a fifth massive planet, ejected during all of these migrations.)

Each of the giant planets formed from a collection of moons, but these moons were reshuffled as the planets migrated. With all the complicated gravitational dynamics, some planets lost moons while others gained new ones.

So Uranus could have been born with a massive moon or it could have been captured quickly. And if the moon were big enough, it could have started playing with the planet’s rotation.

Uranus probably started with a random but small tilt. Over time, this tilt will precess, as astronomers call it, wobbling the planet’s direction of rotation like a giant spinning top. (Earth does the same.) Normally, a moon doesn’t care about the precession of its planet’s tilt. But it’s possible for a moon to lock into a resonance pattern in which the length of time it takes for the precession to match a whole number of the moon’s orbits.

This resonance allows the moon’s gravitational pull to gently pull on the planet and increase precession. It’s like an invisible cord attached to the top of the planet: over the course of millions of years, this propensity gets worse and worse. As it progressed, the moon’s orbit would creep steadily closer to the planet.

The researchers found that once Uranus had a large enough moon, it would be able to increase the planet’s tilt to over 80 degrees within a few hundred million years. To complete the work, the satellite would then crash into Uranus, fixing the planet’s tilt at its current value.

This scenario would explain why Uranus is so unique: it only had one large enough moon to resonate, which is common – not so common that we should expect the same thing to happen with Neptune. And then it all went sideways from here.

follow us on twitter @spacedotcom and further Facebook.

#Uranus #odd #tilt #work #longlost #moon

Leave a Comment