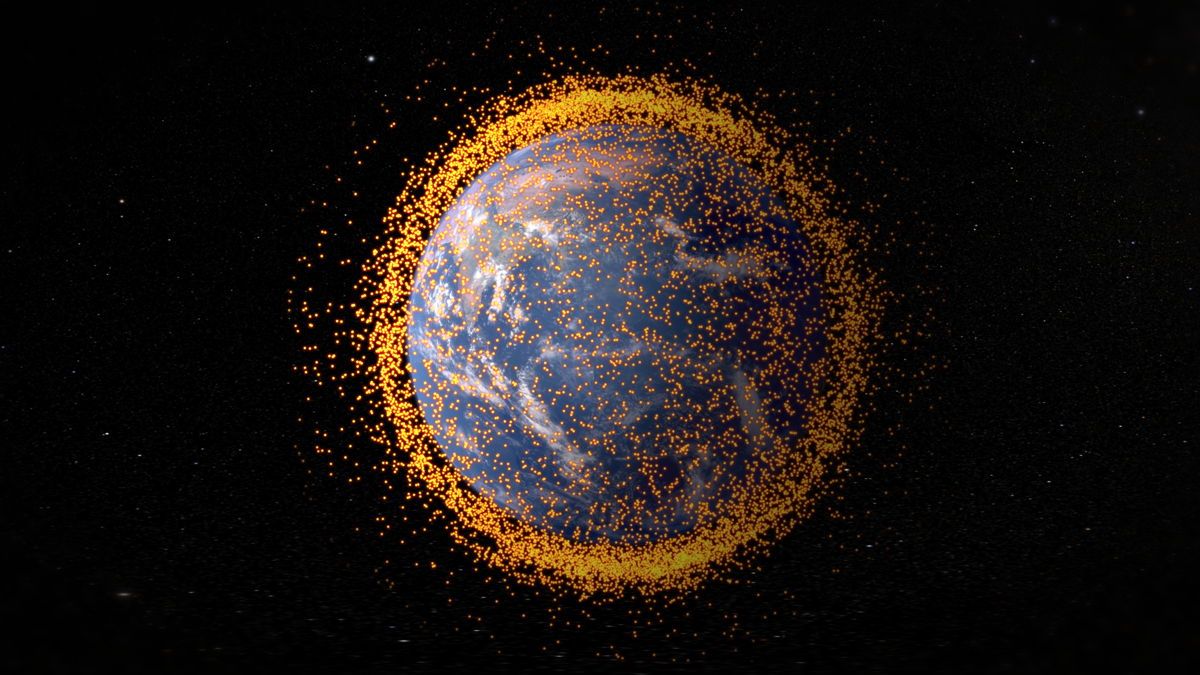

There is much debate these days about how best to deal with our growing space debris problem.

No single answer is likely to serve as a silver bullet, in part because the problem is global. As a matter of fact, space junk Experts have dubbed it the “tragedy of the commons.”

This state of affairs is being exacerbated by the increase in global launch rates, driven in significant part by the assembly of satellite megaconstellations like SpaceX’s Starlink broadband network.

Related: Kessler Syndrome and the Space Debris Problem

Then there’s the associated jumble of dead or dying spacecraft, spent rocket stages, and myriad other pieces of man-made remains, from sewage ejected from solid-fuel rocket engines, to stray nuts and bolts, to paint shavings and droplets gushing away from spacecraft coolant systems radioactive. And just to be safe, throw in fragments from satellites blown apart in anti-satellite tests.

In short, it’s a mess from heaven – with long-term consequences.

“With nearly 5,000 operational satellites and over 30,000 pieces of trackable debris, the ability to operate safely in space is becoming increasingly difficult,” Paul Bate, chief executive of the UK Space Agency, said in a statement (opens in new tab) Last month.

High ambition

For many years, several ideas have been put forward clean up the space environmentincluding fish-like nets, harpoons, laser beams, deorbiting tethers, solar sails, and grappling by spacecraft equipped with robotic arms.

However we are able to “clean up the trash” in orbit would lead us towards space sustainability – the ability of all spacefaring nations to continue using space for the benefit of all.

That’s a lofty goal, yes, but it’s one that’s being addressed by the Orbital Sustainability Act of 2022 (opens in new tab) (ORBITS Act), which was introduced in the US Senate on September 12. The bipartisan bill aims to “establish a demonstration program for active remediation of in-orbit debris” and “to encourage the development of unified standard practices for in-orbit debris.” a safe and sustainable orbital environment.”

Then there is the action of the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to formulate new rules to reduce the risks posed by in-orbit debris by reducing the time that defunct satellites stay aloft. The FCC recently voted in favor of decommissioning low-Earth orbiting satellites within five years, rather than the 25 years previously recommended to satellite operators.

“The changes that have been made seem to go in the right direction,” said Don Kessler, a now-retired NASA senior scientist who conducted pioneering research on orbital debris. In fact, the Kessler syndrome – a dreaded cascade of collisions with space debris that would create increasing clutter in orbit – is named after him.

“The FCC could become the regulatory agency that ensures NASA guidelines are being followed,” Kessler told Space.com. “Crunning the ’25-year rule’ to five years would be a significant improvement given the large number of low-Earth orbit constellation operators who said they could easily meet a five-year rule. The FCC will need NASA’s debris models to predict the outcome of any proposed changes.”

Related: Clean Up Space Debris: 7 Wild Ways to Destroy Orbital Debris

Deal with the situation

The FCC’s adoption of a five-year rule for getting things out of orbit would be “a step in the right direction,” said TS Kelso, senior research astrodynamicist at Analytical Graphics, Inc. and director of the Center for Space Standards and Innovation’s Space Debris Authority in Colorado Springs and Wailuku, Hawaii. However, he added, “it’s quite simply not enough.”

“We need to change how people think about the space environment,” Kelso told Space.com. “While it seems like a somewhat ambiguous goal, we cannot make real change without getting people to change their fundamental view of what should be done. Not how it could be done.”

It’s one thing to recognize that pollution of the near-Earth space environment is bad, Kelso said, but it’s quite another to accept that we should change our behavior.

“People in particular — both inside and outside the space community — should recognize that once their mission is complete, we shouldn’t leave things in orbit,” he said. “So a rocket used to launch a satellite should be removed once it has placed its payload in orbit. The same applies to a satellite that has reached its planned end of life. Get it out of orbit while it still has fuel and is controllable.”

competition phase

Many experts say it is important to take action against space debris now, because low earth orbit (LEO) will become increasingly dense in the future.

“The market for LEO constellations is in the early stages of growth, with every indication that it will become a dynamic market,” said Brad King, CEO of Orbion Space Technology in Houghton, Michigan.

“The benefits of LEO constellations are now undeniable. Early entrants like Planet and SpaceX have shown that it is possible to deploy large constellations and that the satellites can bring disruptive and valuable benefits to the global economy and society,” King told Space.com. “Once the planet becomes accustomed to these services from space, we will integrate them into our lives and we will expect them and take them for granted.”

The market is now entering a competitive phase, King said, where multiple companies are looking for the right business model and learning from each other’s successes and failures.

“After this phase comes consolidation, where the successful companies merge and/or acquire less successful competitors, and eventually stabilization into a less dynamic list of companies that become long-term space providers,” he said.

Right now, the biggest risks to space sustainability are orbital debris and traffic congestion, King said. “Both of these can lead to collisions, compounding the problem,” he said. Orbion’s propulsion systems, he added, allow each satellite to maneuver during its mission and also safely dispose of itself when its time is up.

Both of those skills are important for preventing space collisions, along with knowing where space objects are and sharing that information with other operators, King said.

Related: SpaceX’s Starlink satellite megaconstellation launches in photos

The cost of doing nothing

How were dying spaceships supposed to crash themselves? There are multiple options, each with a cost, Kelso said.

Using a high-thrust deorbiting method would require additional fuel and the added weight of a larger engine, but would remove an object faster and more likely in a controlled manner, Kelso said. Using a low-thrust method, he continued, can cost less upfront, but keeps the object up longer and poses an increased risk of collision, and the ability to control where re-entry occurs is reduced, reducing the risk from damage to the earth’s surface increased.

“These risks and the possible consequences must be weighed against the upfront costs. But it also doesn’t cost anything to do nothing, and as we’re beginning to understand, it’s going to be more expensive to fix things later than to simply prevent this from being a problem in the first place,” said Kelso. “We would have done that by now from any other environment, that we have polluted shall learn.”

disposal plan

According to Kelso, every launch should include a disposal plan for all objects it sends into orbit.

“Perhaps there is an incentive program to get satellite operators and launch providers to stick with their plan, such as a ‘deposit’ that is paid before launch and is fully refundable if the disposal plan is executed as planned,” he said .

Kelso’s conclusion is that near-Earth space, like air, land, and water resources, is not limitless.

“Once people accept that and advocate for a sensible approach of ‘unpacking’ everything we ‘package’, getting launch providers and satellite operators to work toward that goal should just be the right thing to do,” he said. “Then the industry can innovate to determine how best to achieve those goals.”

Leonard David is the author of the book “Moon Rush: The New Space Race (opens in new tab)‘ published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has covered the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).

#Controlling #space #debris #require #change #attitude

Leave a Comment