More and more people in the UK are choosing to freeze their eggs, sperm and embryos to use for their own fertility treatment. Previously, the storage limit was ten years, but extensions were permitted up to the age of 55 if there was proven medical necessity (e.g. premature infertility).

However, many felt that the storage restrictions limited the choices of people who freeze eggs and sperm for their own fertility treatment. If they could not provide a medical reason for extending the storage period, these gametes had to be destroyed after ten years.

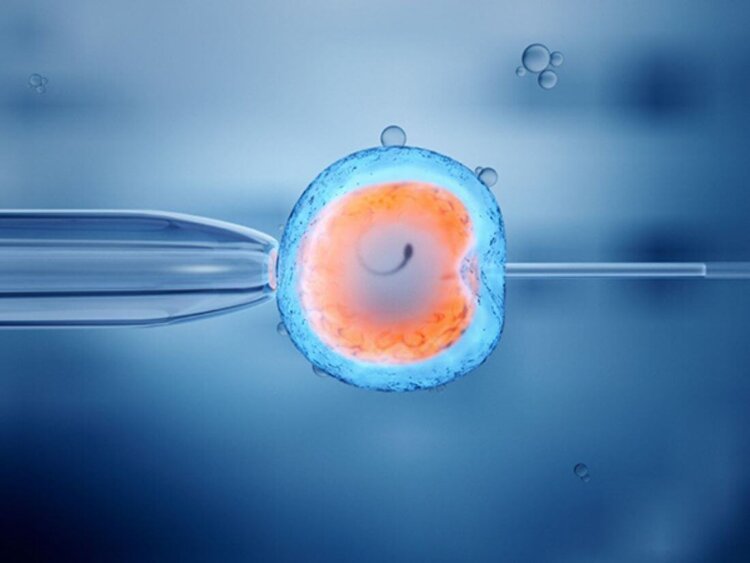

Cryopreservation techniques – in which gametes are frozen for their preservation – have also improved significantly since the previous storage limits were established. Studies now show that eggs frozen using current preservation techniques are likely to develop in the same way as fresh eggs. Frozen embryo pregnancy rates are also comparable to fresh embryo transfer. There is no longer any scientific reason to limit storage to a maximum of ten years.

After launching a public consultation in February 2020, the government has now enacted legislation to extend the retention period to 55 years for everyone (regardless of medical necessity).

consideration for donors

After the storage limit change (which went into effect on July 1st), people now have to give their consent every ten years to continue storing their gametes and embryos for use in their own fertility treatment. However, egg and sperm donors not seeking fertility treatment will not be asked to renew their consent every ten years – although they can indicate in advance whether or not they wish to keep their donation for up to 55 years.

These new storage times may have important implications for donors and children born from donated eggs or sperm. Although advice is already being offered to donors to ensure they are happy with what they will do, advice now needs to address the issues raised by the extended retention period. The most significant of these problems is that some donors’ eggs or sperm will be available for use for a significantly longer period than under the previous regulations. The obligation on clinics to ensure donors fully understand the implications of their decision will become even more important when this retention extension is implemented.

For example, if a person donates sperm at the age of 35 and their sperm is stored for 55 years, children may be born from that donation when the donor is 90 years old. It also means that the children born of that person’s donation may have donor siblings who are older than their parents. Individuals conceived by a donor should be aware of the possibility that their donor could be a very old – or deceased – individual and that they could have donor siblings and possibly nephews and nieces who are significantly older than them.

This change comes against the background that since the law was changed in April 2005, persons conceived by a donor aged 18 have the right to find out who their donor was.

Fertility experts are also concerned about the speed at which these potentially sweeping changes are taking effect – leaving little time to prepare. Although the changes are already in place, fertility clinics still need to adopt new policies and train and educate staff. Many clinics have also been unable to produce updated advice for donors. This is important to ensure that everyone fully understands who they are consenting to.

It is also important to ensure that people who wish to undergo fertility treatment using donated eggs and sperm are fully informed of the impact that changes in retention periods could have on starting a family in this way. Although the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology already has information available on what to consider when donating or accessing fertility treatment using donated gametes, it will be important for UK fertility clinics to produce their own information that reflect changes in retention limits.

The effects of this change in the law will last for many years. Extending the maximum storage time of oocytes and sperm clearly has significant benefits for those who need to use them for their treatment. However, sooner rather than later, attention needs to be paid to the implications that these changes will have for gamete donors and humans conceived by donors.

Caroline Redhead is a research fellow on the ConnecteDNA study at the University of Manchester’s Center for Social Ethics and Policy. Follow Caroline on Twitter @cabr88

is a Research Fellow at the Center for Social Ethics and Policy, University of Manchester. Follow Lea on Twitter @leagilman84

is Lecturer in Human Reproductive Biology, University of Birmingham.

is a Reader in Bioethics, University of Manchester.

A version of this article was published by The Conversation and is used here with permission. Check out The Conversation on Twitter @ConversationUK

#fertility #treatment #eggs #sperm #shelf #life #century #heres

Leave a Comment