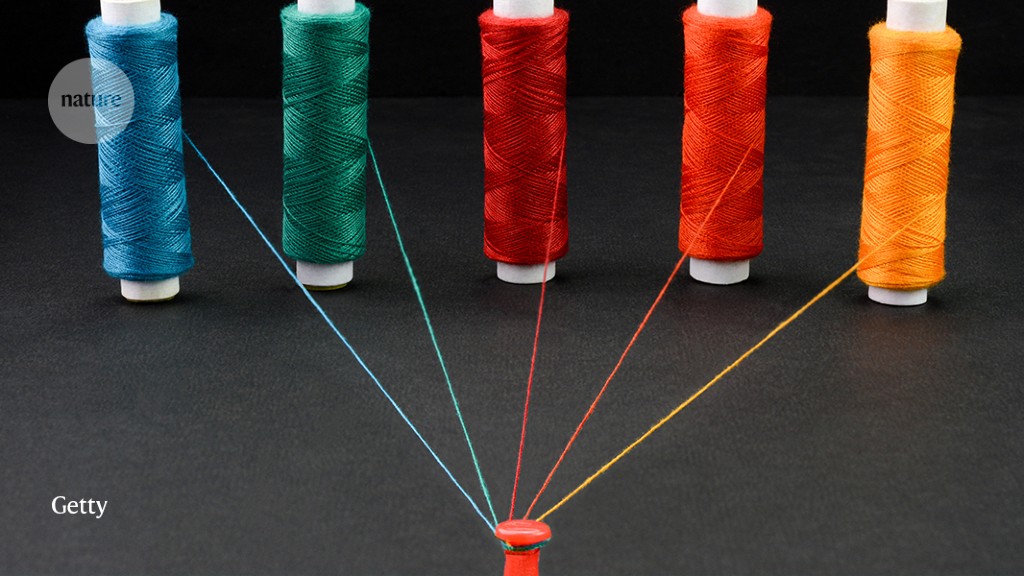

Your tenuous social ties, not your closest associates, might be your best source of information about job prospects.Photo credit: Getty

When it comes to getting a job, there’s a saying, “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know.”

In fact, science shows that how you know them also matters. Researchers in the United States have proven a long-standing social science hypothesis: that people are more likely to get into high-paying jobs through friends of friends or “weak ties” than through their close friends or family.

In a publication in Science Last month US scientists described how they were able to establish a causal link between weak attachment and job offers by sifting through data from the social media network LinkedIn1. The team analyzed data from LinkedIn’s “People You May Know” algorithm, which suggests new connections to users.

Hire and be hired: Faculty members tell their stories

“These platforms are constantly experimenting with algorithms,” says co-author Sinan Aral, a network scientist at the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. LinkedIn had been experimenting with different binding strengths for its connection algorithm. Aral and his co-authors looked back at this data and found that weaker ties resulted in more job “transfers,” or more instances of people getting new positions, than strong ties—but only up to a point. Very weak links, where new links had little mutual contact, yielded no employment dividends.

The authors also found that weak ties were more important for job mobility in highly digitized industries—measured by those industries’ skill requirements in information technology, robotization, and remote work, among others—than in less digitized industries. This finding could be of interest to academic recruiters as well as academics looking for employment opportunities. Although Aral and his co-authors didn’t specifically study researchers, he believes that most science jobs fall into the highly digitized category. “Science is information work in many ways – there is a lot of data analysis [and] share,” he says.

The Strength of Weak Bonds

So how do weak connections fuel these successful connections? It’s all about access to novelty. “The theory behind the strength of weak ties was that people who don’t know you well have different types of knowledge than you and your close friends do,” says co-author Erik Brynjolfsson, director of the Digital Economy Lab at the Stanford Institute for Human -Centered Artificial Intelligence in California.

However, our finding of an inverted U-shaped relationship between attachment strength and job mobility challenges that assumption, says Aral. There might be a trade-off between novelty and amount of information, he says. At the weakest links, the connected parties receive a trickle, not a stream. “I think literature really needs to go back and look at that.”

The Business of Science

The study highlights how important weak ties are to people’s careers, says Theresa Kuchler, an economist and finance specialist at New York University’s Stern School of Business in New York City. It raises important questions about the underlying mechanisms of the “strength of weak ties” hypothesis, she adds. Such work could help recruiters understand and address factors that stifle diversity in careers, such as glass ceilings that subtly exclude certain groups of people from advancement in a profession.

One question, Kuchler says, is whether people get information about new jobs through their networks — or whether the connections act as recommendations that help employers identify good recruits. Another question is whether hiring based on weak ties leads to better recruits or just more convenience for the recruiter – something she says could perpetuate inequalities in the job market. “Perhaps we also want to learn how bonds are formed and how people or groups of people who currently lack the necessary bonds can build them,” says Kuchler.

Brynjolfsson says he expects many more studies of this type in the future. “We are in the midst of a measurement revolution due to the digitization of not only the connections at work, but the digitization of much of the business and economy,” he says. “The research in our work exemplifies the kind of large-scale, causal inference that was impossible until recently but will soon be widespread.”

#job

Leave a Comment