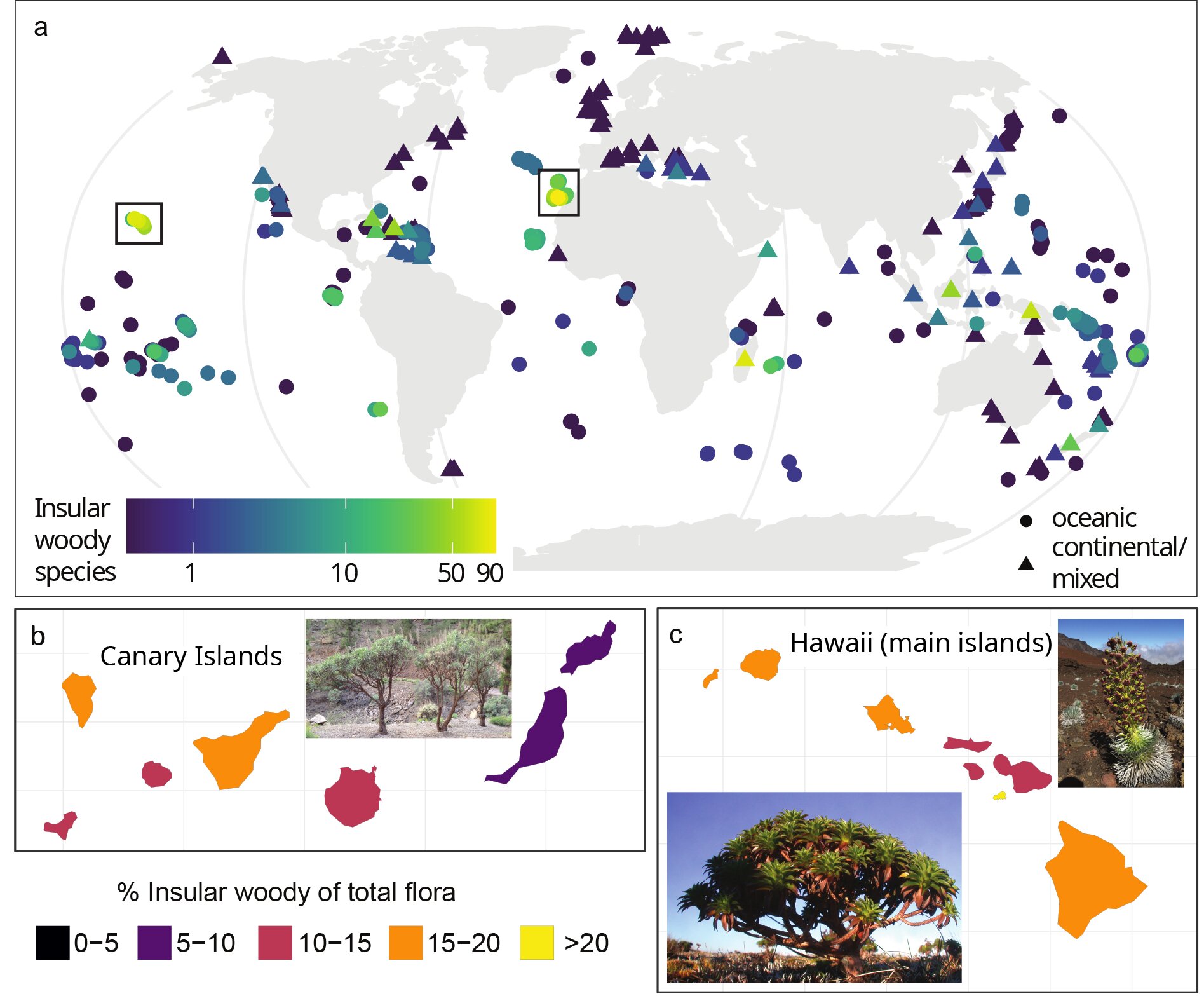

a) The number of island trees on all islands. b,c) Percentage of island trees in the total flora on the Canary Islands and Hawaii. The inlet images show three iconic examples of island lignification: Echium virescens in the Canary Islands, Argyroxiphium sandwicense, and Dubautia waialealae in Hawaii. Photo credits: F. Lens and Seana Walsh and Ken Wood/National Tropical Botanical Garden, Hawaii.

Why do some plants grow into large woody shrubs or colossal trees while others stay small and never produce wood in their stems? It’s an evolutionary puzzle that puzzled Charles Darwin more than 160 years ago. Now, scientists from the Netherlands and Germany present the first global overview of island lignification evolution that will finally help solve the mystery.

“The first woody trees evolved on Earth about 400 million years ago, but we still know so little about why they evolved wood in the first place,” says Frederic Lens, a researcher at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center and Leiden University. All of these early woody plants are now extinct and arose under unknown climatic conditions, making it impossible to understand the evolution of lignification from their fossils, but islands may offer the solution.

Lignification evolution still occurs today, particularly in areas known as natural laboratories of evolution: islands. One of the most striking aspects of island floras is that they are proportionally more woody than those of neighboring continents. Charles Darwin described this phenomenon as island lignification. It occurs when a non-woody continental colonizer reaches an island and subsequently evolves into a woody shrub or even tree on the same island after tens or hundreds of thousands of years.

Insular woodiness is known only from a few iconic lines, like the Hawaiian silver swords. To better understand why plants became lignified during evolutionary history, the Dutch-German research team compiled a new database encompassing over a thousand island wood species and their distribution, which allowed them for the first time to rigorously test a number of existing hypotheses – with promising results Results.

“We have identified an association between increasing drought and increased lignification in plant stems on islands. I’m convinced that the connection between drought and lignification will be much stronger on continents,” says Lens. The team plans to test this soon when they analyze their entire database, including about 6,000 additional tree species that evolved their lignification on continents.

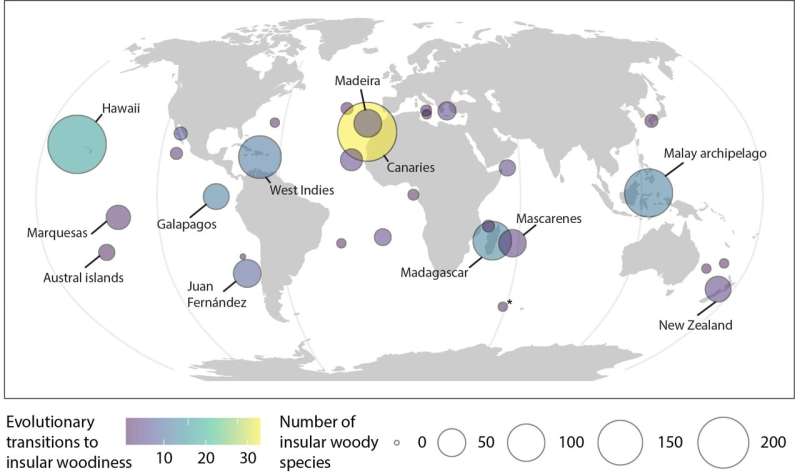

Minimum number of evolutionary shifts to island groves and number of island groves on archipelagos worldwide. For clarity, only archipelagos with at least one evolutionary shift are shown. The * summarizes several islands in the southern Indian Ocean. Photo credits: Kerguelen, Crozet, Prince Edward Islands and Heard & MacDonald

Hot spots

Not only did the researchers identify all of the world’s island woody plants, they also globally mapped their distribution and number of transitions, and tested which of the evolutionary hypotheses are the most likely. “It was really crazy to even put together a data set like this,” says Frederic Lens. “It took me more than 10 years to complete the database, but luckily it all paid off in the end.”

The new lignification database found more than three times as many previously known island trees. These 1000+ species are the result of at least 175 independent transitions. “This clearly underlines that islands are remarkable biodiversity hotspots in the world, with a unique flora that urgently needs to be protected,” says first author Alexander Zizka from the University of Marburg in Germany.

The extensive research also offers an interesting glimpse into the future. “Given the dry European summer of 2022, the fact that drought is emerging as one of the most likely drivers of wood formation offers promising research opportunities in agriculture to secure our food production,” says Frederic Lens.

“Assuming we could convert any non-woody plant into a woody plant, not only would we have larger harvests with a higher yield per plant, but more importantly, we could also increase the drought tolerance of these woodier plants.” In a world facing climate change and a growing global population, this is simply essential.”

The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Protecting trees in Xishuangbanna requires a multidimensional approach

Alexander Zizka et al, The evolution of island lignification, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2208629119

Provided by the Naturalis Biodiversity Center

Citation: Why Plants Became Woody Worldwide (2022 September 9) Retrieved September 10, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-09-worldwide-woody.html

This document is protected by copyright. Except for fair trade for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is for informational purposes only.

#plants #lignified #worldwide

Leave a Comment