- Mun Keat LooiInternational features editor

- The BMJ

- mlooi{at}bmj.com

Is Covid settling into a pattern?

“It seems that there are two to three waves per year, each caused by new variants,” says Atsushi Sakuraba, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, USA. “Given the nature of SARS-CoV-2, an RNA virus that mutates over time, this pattern is likely to persist.”

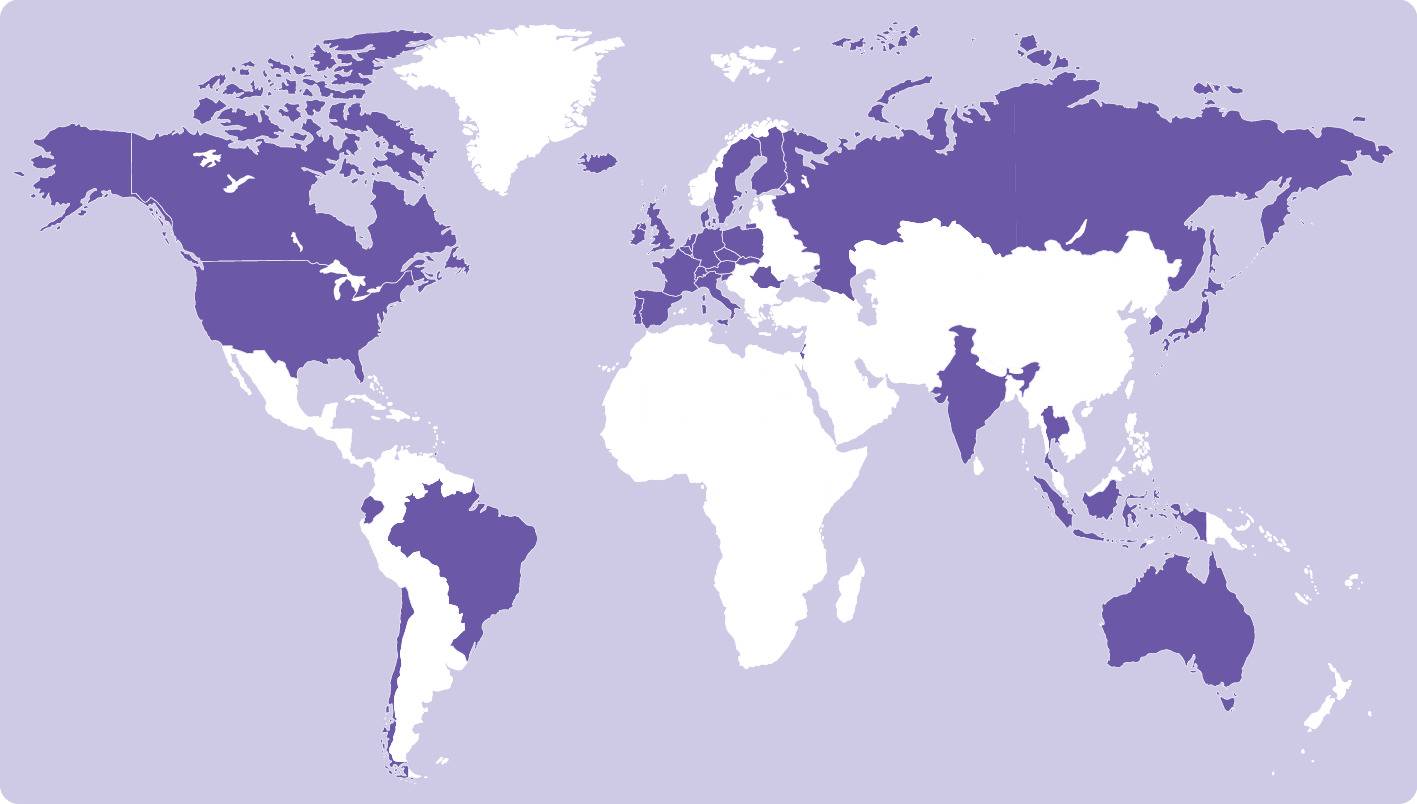

The dominance of each new variant—usually through increased transmissibility or through mutations that help it partially evade immunity and allow reinfection—comes from overcoming existing variants and leading to a surge of infections, aided by the loosening of the Restrictions and dwindling vaccine immunity (Fig. 1).

“>

waves of infection

Photo credit: Our world in data

Lawrence Young, a virologist at the University of Warwick, UK, says: “We get plateaus [peaks in case numbers] between waves of infection, and the set point for these plateaus is a bit higher each time as the virus changes.

“What we are seeing right now is essentially the evolution of this virus in real time. We see these waves of infection with the different variants that simply outperform their predecessors.”

Are there regional patterns?

Some countries like New Zealand and Japan have experienced extremely large increases followed by large falls compared to other countries. These countries maintained comparatively very low infection numbers for over a year before restrictions were eased, thanks to a combination of tough measures such as border closures and high levels of public compliance.

What is important for these countries, says Joël Mossong, epidemiologist at the Luxembourg Health Directorate, is not the transmissibility of the new variants as such, but the level of immunity of the population.

“The reason they’re sweeping through is because they can really find people who haven’t been infected yet or who were infected a long time ago,” he explains. “And they are able to avoid or evade the immunity they already have, either through a vaccine or through a previous infection that was based on a previous variant.” All existing Covid-19 vaccines are based on the original ‘wild-type’ -Tribe.

Will these patterns continue?

Young says, “As long as these variants continue to be selected for increased transmissibility and immune evasion, particularly for current vaccine protection, we will continue to see this type of pattern around the world.” But it depends on the variations and where you are.”

We can expect the wave pattern to continue for years to come, he adds, unless we become more proactive on mitigations or our vaccines adapt.

Mossong says, “It looks like there are [new] Variants are flipped through every three months. . . but it also looks like each subsequent wave will be smaller. It really seems to me that the virus is wiping out any pockets of vulnerability that still exist in the population.”

There’s a lot of immunity in the population now, he says, as most people have been vaccinated, but also result from “natural” exposure to the virus, as most people have also been previously infected. “Infectious diseases are very similar to bushfires,” he says. “People are the equivalent of trees that have not yet been burned.”

What happened to the previous variants – and could they come back?

Sakuraba explains, “The old variants are still being discovered in small numbers but are not likely to become dominant as the majority of the world is now vaccinated with vaccines effective against them.”

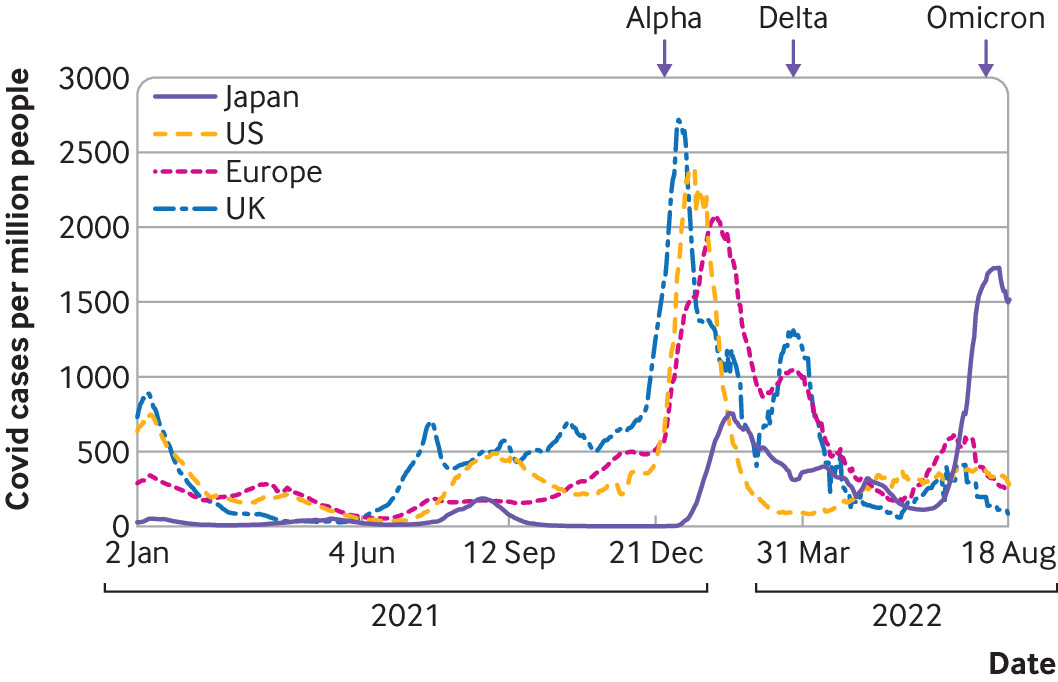

With the supremacy of the Omicron family (Fig. 2), it is unlikely that a previously dominant variant could re-enter the ring. Mossong says any previous variant would find it difficult to reestablish dominance or even gain a foothold. “It really was vaccines that killed them,” he says. “It really built up a lot of immunity against them. I think it’s unlikely that any of them will come back.”

“>

Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 sequences that are the omicron variant (dark shaded areas), August 15, 2022

Photo credit: Our world in data

Eleanor Riley, Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the University of Edinburgh, UK, says that in hindsight, “the alpha and beta variants really weren’t that contagious — although they looked like many infections at the time — compared to how easily omicron and Deltas before that are spreading.” Back then, there were no vaccines or waning immunity.

“To come back and take over omicron, they would have to be completely different immunologically,” she says The BMJ. “And I’m not sure if that would be enough immunologically to counteract the fact that they’re actually not that contagious compared to the two in front.”

An exception might be people who are immunocompromised or immunocompromised, who might harbor multiple infections from different variants or sublineages, Young and Mossong say. This could be an evolutionary opportunity for gene swapping – for example, in March 2022 there were media fears about “Deltacron”.1

A preprint published on July 2 by researchers at Yale University, USA, described a 60-year-old immunocompromised patient who harbored an earlier variant, B.1.517, since November 2020.2 The researchers say it evolved twice as fast like the wild type of SARS-CoV -2, thanks to the lack of immunity of the patient. The lead author, Nathan Grubaugh, told the magazine Science that some of the viruses circulating in patients today could qualify as new variants if found in the community.

Leave a Comment