RResearch at Boston University testing a lab-made hybrid version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is making heated headlines claiming the scientists involved may have unleashed a new pathogen.

There is no evidence that the work carried out under Biosafety Level 3 precautions at BU’s National Laboratories for Emerging Infectious Diseases was improperly or unsafely performed. In fact, it was approved by an internal biosafety review committee and the Boston Public Health Commission, the university said Monday night.

However, it has emerged that the research team did not clear the work with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which was one of the funders of the project. The agency said it will be looking for answers as to why it first learned about the work through media reports.

advertisement

Emily Erbelding, director of NIAID’s Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, said the BU team’s original grant applications did not specify that the scientists wanted to do exactly this work. The group also did not make it clear in the progress reports it submitted to NIAID that it was conducting experiments that might involve amplification of a pathogen with pandemic potential.

“I think we will have talks in the coming days,” Erbelding said in an interview with STAT.

advertisement

When asked if the research team should have informed NIAID of their intention to do the work, Erbelding said, “We wish they had, yes.”

The research has been posted online as a preprint, meaning it has not yet been peer-reviewed. The senior author is Mohsan Saeed of BU’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories. STAT contacted Saeed on Monday but received no response as of the publication of this article.

In comments via email, the university later denied claims by some media outlets that the work created a more dangerous virus.

The email from Rachel Lapal Cavallario, associate vice president of public relations and social media, said the work was not, as claimed, a benefit of functional research, a term that refers to the manipulation of pathogens to make them more dangerous close. “In fact, this research made the virus [replication] less dangerous,” the email said, adding that other research groups have done similar work.

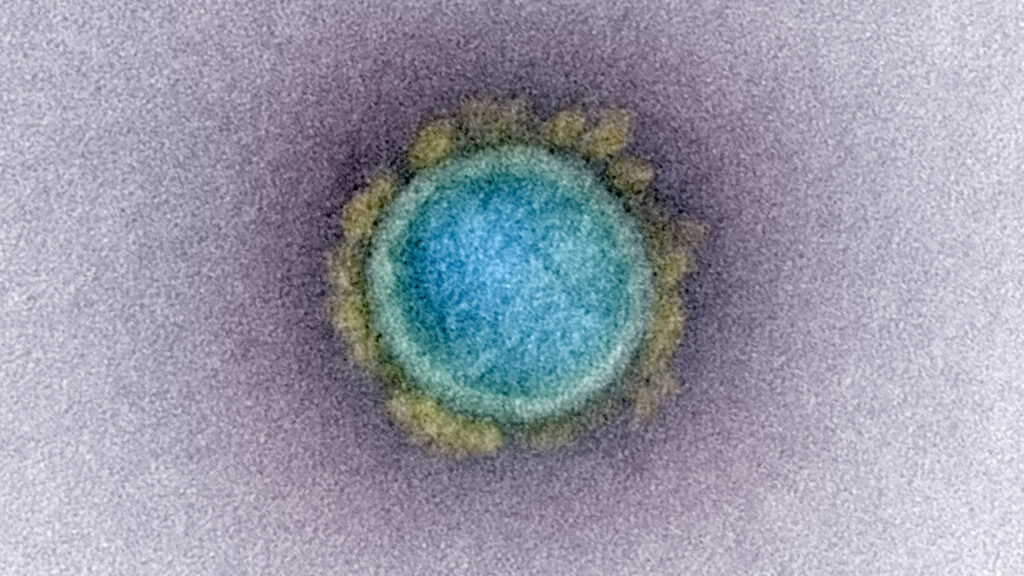

In the paper, Saeed and colleagues reported on research they were conducting to create a hybrid, or chimeric, virus – in which the spike protein of an omicron version of SARS-2 was fused to a virus from the Wuhan strain, of the original version originating in China in 2020. Omicron viruses first emerged in late 2021 and have since fragmented into several different subvariants.

The aim of the research was to determine whether the mutations in the omicron spike protein were responsible for the increased ability of this variant to evade human-built immunity to SARS-2 and whether the changes resulted in a lower severity of omicron.

However, the tests actually showed that the chimeric virus was more lethal to one species of laboratory mice than Omicron itself, killing 80% of infected mice. Importantly, the original Wuhan strain killed 100% of the mice it was tested on.

The conclusion of the study is that mutations in the omicron variant spike protein are responsible for the strain’s ability to evade the immunity that humans have built up through vaccination, infection, or both, but they are not responsible for the apparent reduction in the Omicron virus severity.

“Consistent with studies published by others, this work demonstrates that it is not the spike protein that drives omicron pathogenicity, but other viral proteins. Identifying these proteins will lead to better diagnostic and disease management strategies,” Saeed said in a comment distributed by the university.

Research that has the potential to make pathogens more dangerous has been a hot topic for years. About a decade ago, a high-profile debate over whether it was safe to publish controversial studies on a dangerous bird flu virus, H5N1, led to a rewrite of the rules for this type of work. A further review of the policy is underway under the direction of the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity.

The controversy surrounding research into pathogens with pandemic potential has been gaining ground since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, which some scientists and others believe is an accidental or intentional result of bat coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China may have been the city where the pandemic is believed to have started. (There’s plenty of evidence to suggest the virus spread from a wet market in the city, not from the Wuhan lab. But proving something didn’t happen three years later is a challenge that might be impossible to meet is.)

Under NIAID policy, proposals for federally funded research that could produce so-called enhanced pathogens with pandemic potential should be referred to a committee that assesses the risks and benefits of the work. The policy is known as the P3CO framework.

Erbelding said NIAID would likely have convened such a committee in this case if it had known that Saeed’s team was planning to develop a chimeric virus.

“What we wanted to do is talk about exactly what they wanted to do upfront, and if it had met what the P3CO framework defines as an enhanced pathogen with pandemic potential, ePPP, we would have a package to review through who can present a committee convened by HHS, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. That’s what the framework says, and that’s what we would have done,” she said.

However, Erbelding noted that some of the media coverage of the study overestimated the risk the work might pose. “That 80% kill rate, that headline doesn’t tell the whole story,” she said. “Because Wuhan” – the original tribe – “killed all the mice”.

The mortality rate seen in this strain of mice when infected with these viruses raises the question of how well they model what happens when humans become infected with SARS-2. The Wuhan tribe killed less than 1% of those infected.

Virologist Angela Rasmussen, who was not involved in the research, had some sympathy for the BU scientists and said the rules as currently written were ambiguous.

“Since much of the definition of ePPP relates to ‘reasonable expectation’ of human outcomes (and animal models aren’t always a good guide for that), it’s very difficult for researchers to say, ‘Oh yes, that’s ePPP,'” wrote Rasmussen in response to questions from STAT.

“When in doubt, I would personally contact NIAID, but it’s often not obvious when additional guidance is needed. And because it’s not very transparent, it’s difficult to use other decisions that NIAID has made as examples,” she said.

“I’m very tired of people saying that virologists and NIAID are reckless or don’t care about biosafety,” said Rasmussen, a coronavirus expert at the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization. “The problem isn’t that. The problem is that the guidelines and expectations for many experiments aren’t clear, and the process isn’t transparent.”

— This article has been updated to include comments from Boston University and the paper’s senior author.

Get your daily dose of health and medicine every weekday with STAT’s free Morning Rounds newsletter. Sign up here.

#Tests #Boston #University #researchers #labmade #version #Covid #virus #draw #government #scrutiny

Leave a Comment