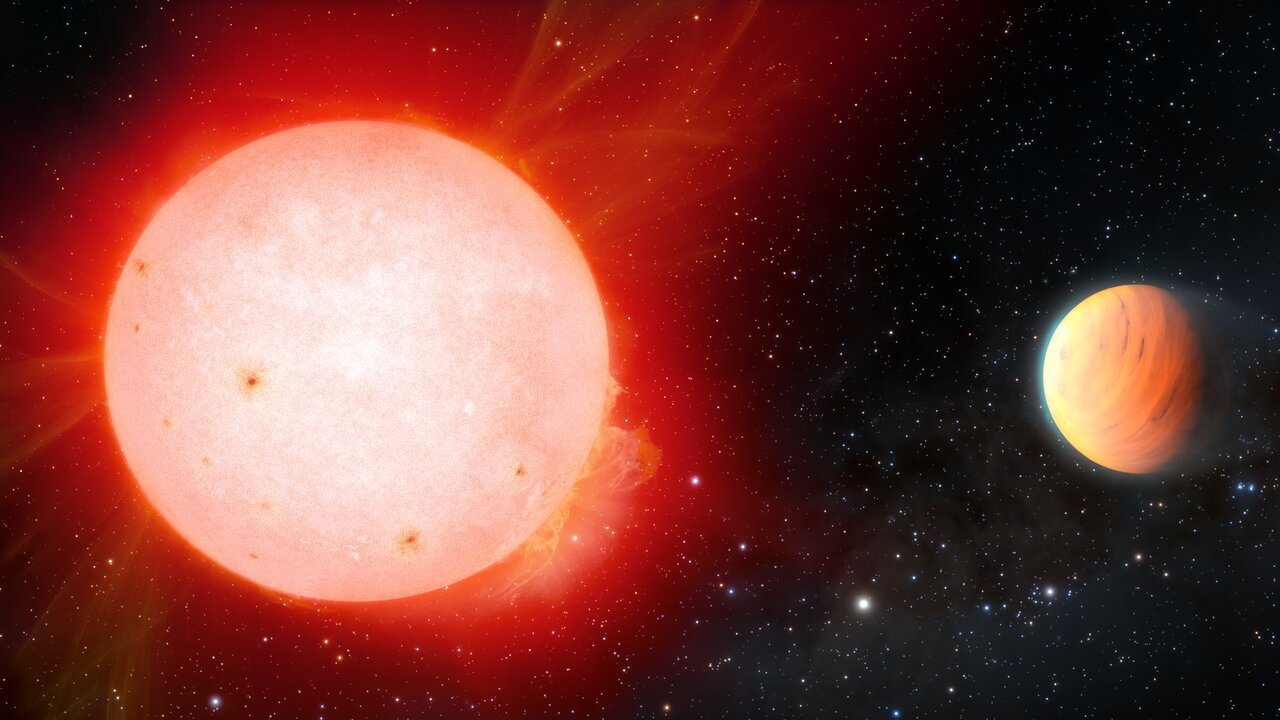

The Exoplanet Discovery Room is home to all sorts of interesting “super” worlds. There are Super Earths, Super Neptune and of course Super Jupiter. Recently, the WIYN telescope on Kitt Peak, Arizona, performed a follow-up observation of a gas giant spotted by TESS (the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite). The world is fluffy and strange, orbiting a red giant star. Oddly enough, it shouldn’t even exist. But there it happily orbits a star about 580 light-years from Earth.

The gas giant planet in question is called TOI-3757 b. Based on measurements from WIYN and TESS, as well as other telescopes, it turns out that the average density of TOI-3757 b is 0.27 grams per cubic centimeter. It’s less than half the density of Saturn and about a quarter the density of water. That’s about the density of a marshmallow. Such an inflated property is hard to believe, especially since the star it orbits isn’t exactly the best place to harbor gas giants.

“Giant planets around red dwarf stars have traditionally been considered difficult to form,” says Shubham Kanodia, a researcher at the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Earth and Planets Laboratory and first author of a paper on TOI-3757 b published in The Astronomical Journal. “So far, this has only been studied with small samples from Doppler surveys, which have typically found giant planets further away from these red dwarf stars. Until now, we have not had a large enough sample of planets to reliably find nearby gas planets.”

Remove all ads on Universe today

Join our Patreon for just $3!

Get the ad-free experience for life

How a red dwarf threatens a gas giant

Why aren’t red dwarf star systems such optimal habitats for fluffy giant planets? They are certainly cooler than their brighter, larger counterparts in the star family. You’d think that would make them a little more welcoming to the gas giants. But even these little stars can be active. Astronomers see that from time to time they emit powerful flares that can destroy a planet’s atmosphere. So how did TOI-3757 b get there? The research team has a few ideas to explain this mystery.

It is possible that the particularly low density of TOI-3757 b is due to the formation of its interior. Typically, gas giants are born with rocky cores that can be up to about ten times the mass of Earth. Their gravity pulls in huge amounts of gas from the protoplanetary nebula. This is how you get Jupiter and Saturn, for example. It is likely that this was not the case with TOI-3757 b. Its red dwarf star is not very rich in heavy elements compared to other M dwarfs with gas giants. This is an important note. That means the planet’s rocky core formed more slowly. This is because it took longer to collect enough rock material from the nebula. If that’s true, then the planet didn’t accumulate quite as much gas during its formation, affecting the planet’s overall density.

There is a second clue that could explain the Marshmallow Planet. Its elliptical orbit brings it closer to the star at certain times. This heats up the atmosphere more than normal and causes it to balloon.

Dipping in the marshmallow

Of course, there is much more to learn about this planet, and astronomers are eager to study it in more detail. “Possible future observations of this planet’s atmosphere with NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope could help shed light on its bloated nature,” said Jessica Libby-Roberts, a postdoctoral researcher at Pennsylvania State University.

This is especially true since finding just one such planet around a red dwarf means there are likely more of them out there. In the grand scheme of exoplanet studies, understanding a bloated Jupiter orbiting an active cool star will give astronomers more insight into how planets form around many different types of stars.

For more informations

‘Marshmallow’ world orbits a cool red dwarf star

TOI-3757 b: A low-density gas giant orbiting a solar-metallic M dwarf

#Astronomers #find #marshmallow #world #lowestdensity #gas #giant #discovered

Leave a Comment