AAnd what hairy beast, whose hour has finally come, slithers toward a lab to be born?

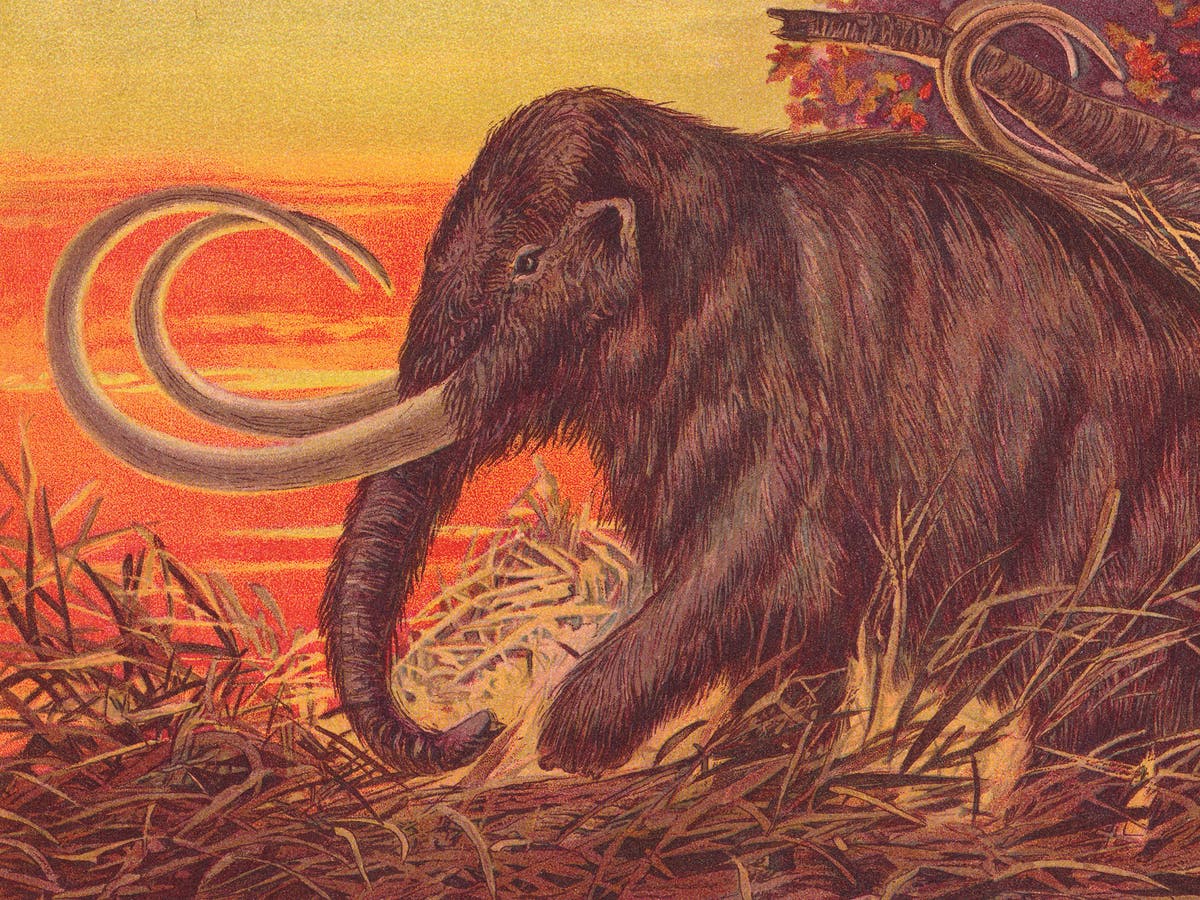

About 3,900 years ago, the last known mammoth breathed its last on the Siberian mainland. Since then, humans have known mammoths only through their remains: scattered bones and a small number of frozen carcasses, complete with the shabby remains of once shaggy fur. These remains have piqued our curiosity for centuries—curiosities that might one day be satisfied. Colossal Biosciences, a Texas-based start-up, is using genetic engineering to bring the species back to life.

“The woolly mammoth was the guardian of a healthier planet,” says the company. Using salvaged mammoth DNA, Colossal will genetically alter Asian elephants, the species’ closest extant cousin. If its plans work out, it will produce a woolly mammoth – or a replica as close as possible to the original – in six years. This year, the company raised $75 million from investors.

Some 3,906 years after it thought it saw us from behind, the woolly mammoth may reacquaint itself with humans — a species that has never seen a large mammal it didn’t like. Their extinction was not solely our responsibility – the end of the Ice Age massively reduced the size of their potential habitat – but, as some paleontologists argue, prehistory is littered with the bodies of the megafauna we ate to extinction. Giant sloths, giant armadillos, dire wolves… whoever was presenting planet Earth should have stayed on the ball back then.

Given the apparent advances in mammoth reconstitution, we might as well be answering the obvious question: should we eat them? Colossal didn’t mention that prospect, instead focusing on the environmental benefits of mammoth remediation: The animal’s heavy gait thickens the permafrost, or the permanently frozen layer of earth, gravel, and sand beneath the Earth’s surface, preventing it from melting and releasing greenhouse gases. “If the ecosystem of the mammoth steppe could be revived,” the company argues, “it could help reverse rapid climate warming and, most importantly, protect Arctic permafrost — one of the world’s largest carbon reservoirs.”

Still, one wonders if people will be tempted to try it like their ancestors did. At some point we will have to decide whether we want to eat woolly mammoths – and indeed any other species that we want to revive. would you eat them

Holly Whitelaw, director of Regenerative Food and Farming, says she’s ready for it. “I would eat anything that was holistically pastured,” says Whitelaw. Stray animals, she says, are good for the soil; They disperse seeds and microbes as they migrate. The healthier the Arctic soil, the more grassland it supports and the more carbon is removed from the atmosphere. “It’s like bringing the wolves back,” says Whitelaw. “You’re bringing the whole layer of the system back up and running.”

It would be a great tragedy if we hoisted these majestic individuals into our time only to use and exploit them for our own benefit

Victoria Herridge, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum and an expert on woolly mammoths, urges caution. In conducting these types of environmental projects, Dr. Herridge The Telegraph“You’re conducting a biotechnology experiment, if that’s your goal [met], will bring about changes on a global scale. The question arises: Who gets to manipulate the planet’s climate system?”

Speak with The Independent, pressed Dr. Herridge expressed additional concerns about the origin of these mammoths. “I have a problem with anything to do with surrogacy,” she says. The genetically engineered mammoth amalgams are hatched in Asian elephants, putting them at significant pain and medical risk.

These are objections to the project itself, not the idea of ending up eating mammoth meat. dr Herridge thinks this scenario is unlikely, but presents a hypothetical scenario in which she would consider eating mammoth meat. “Fast forward 100 years. Imagine that Siberia is not a swamp, there is a place where woolly elephants can roam, they do not wade through a mosquito-infested swamp. Let’s say they managed to breed 20,000 woolly elephants by this point. They have migrated to Banff and are causing havoc and to maintain this population they have had to conduct an annual cull. Would I refuse? no But there are so many caveats.”

Whitelaw says that pasture-raised mammoth has a good ratio of omega:3 to omega:6 fats, making it a good diet choice. With that in mind, it’s easy to imagine Paleo enthusiasts filling consumer demand. dr However, Herridge is again skeptical. “The idea that you can have a diet that goes back to this ancient way is really problematic,” she says. “There’s this naïve idea that there is a lost Eden. Our vision of it is entirely based on wishful thinking and stereotypes.”

Tonight’s dinner? Woolly mammoths in the 2016 film Ice Age: Collision Course

(Shutterstock)

There are other ways of looking at this question. Thinkers like Brian Tomasik, author of the blog Essays on reducing suffering, argue that when you eat animals, “it is generally better to eat larger ones so you get more meat for a horrible life and a painful death. For example, a beef cow provides over 100 times as much meat per animal as a chicken, so switching from all-chicken to all-beef would reduce the number of farm animals killed by more than 99 percent.”

On the issue of eating woolly mammoths, Tomasik says, “A woolly mammoth would weigh about 10 times as much as a meat cow, so eating mammoths instead of smaller animals would further reduce animal deaths.”

We should also consider the mammoth’s manner of death. “Whether death by hunting would be better or worse than a natural death in the wild,” says Tomasik, “depends on how long it takes for the mammoth to die after being shot and how painful the gunshot wound was by the time it died.” .” Wild deer, he says, can take 30 to 60 minutes to die after being shot in the lungs or heart. Their brains are considered too small a target, though mammoths may not.

There are many competing considerations here. While rejuvenation of the Arctic grasslands would likely be good for the climate, it could also bring increased wildlife numbers. Tomasik sees this as bad news. “Almost all wild animals are invertebrates or small vertebrates that produce large numbers of offspring, most of which die agonizingly soon after birth.”

I think it will be a bit like pork

Stronger opposition to the idea comes from Elisa Allen, PETA’s vice president of programs. Allen argues that we should focus on protecting existing species whose habitats are rapidly disappearing, rather than reviving species whose habitats are already lost, saying, “If anything separates humans from the rest of the animal kingdom, this is it selfish desire to eat the other members off when we don’t have to.” Allen says that “the future of the meat industry lies in lab-grown or 3D-printed meat.”

Jacy Reese Anthis, co-founder of the Sentience Institute, sees applying this technology to woolly mammoths as ethically preferable to hunting them. “One of humanity’s most pressing challenges in the 21st century is to end the unethical, unsustainable factory farming industry,” he says. “Cultivated meat is one of the most promising substitutes. So if mammoth meat gets people excited about it, then I’m excited. It would be extremely wasteful to breed and breed live mammoths when we could sustainably grow meat tissues in bioreactors.”

This would avoid what Anthis sees as the inherent wrongness of killing for our own amusement a creature that can think and feel. He’s all for technology, he says, but stresses that it’s important to “uphold the boundaries of respect and physical integrity towards sentient beings. One of the most fertile frontiers was the right not to be owned and exploited for the benefit of others. This is true for humans, but we are increasingly recognizing it for animals as well, and it is a critical pillar of responsible interaction with our fellow creatures.

“It would be a great tragedy if we stretched our technological arm back into the Pleistocene and hoisted these majestic individuals into our time, only to use and exploit them for our own benefit.”

For our ancestors, who built buildings from mammoth bones, this question would not have been half so sensitive. But let’s imagine a mammoth-based dish that doesn’t come from hunting, but from a bioreactor. How could it taste? Whitelaw has a guess. “I think it’s going to be a little bit like pork. You have to cook it long and slow to reduce the fat to make it. Or maybe you could make it nice and crispy.”

Watch out for that fur though.

#Woolly #mammoths #making #comeback #eat

Leave a Comment