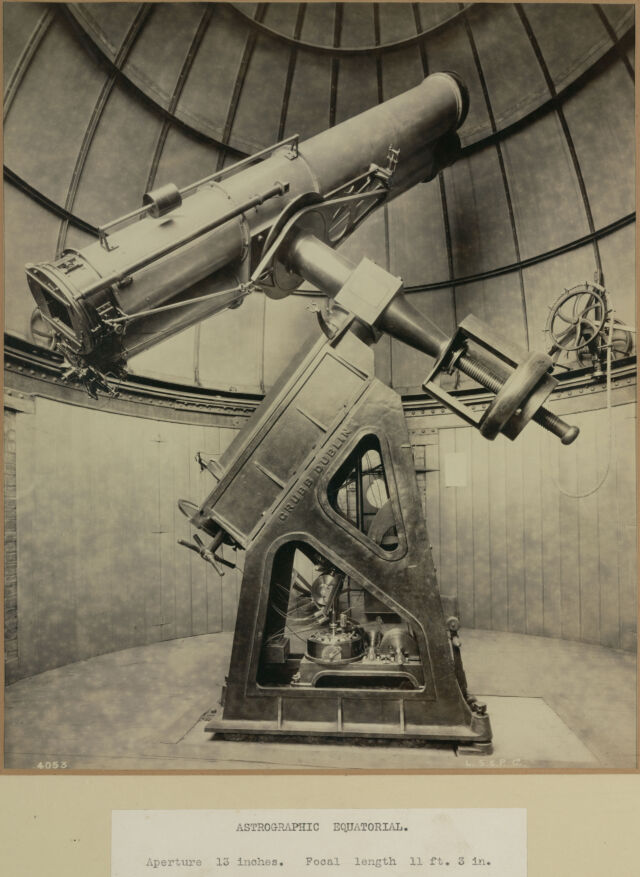

SSPL/Getty Images

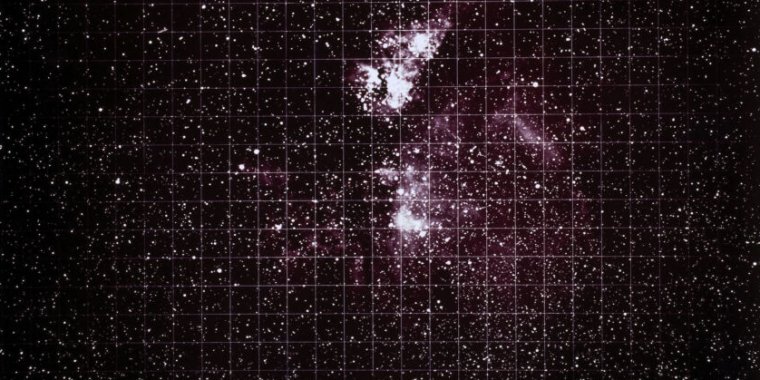

Recently, the European Space Agency released the third batch of data from the Gaia satellite, a public catalog containing the positions and velocities of over a billion stars. This is our latest attempt to answer some of astronomy’s longest-standing questions: How are stars (and nebulae) distributed across the sky? How many are there, how far apart are they and how bright are they? Do they change position or brightness? Are there new classes of objects unknown to science?

Astronomers have been trying to answer these questions for centuries, and the work has been tedious and time-consuming. Capturing what you could see in your telescope lens wasn’t always easy—if you were lucky enough to have a telescope at all.

Now imagine the emergence of a new technique that, for its time, offered some of the advantages of the technology that made the Gaia catalogs possible. It could automatically and impartially record what you see and anyone could use it.

That technique was photography.

This article tells the story of how photography transformed astronomy and how hundreds of astronomers formed the first international scientific collaboration to create the Carte du Ciel (literally “map of the sky”), a complete photographic survey of the sky. This collaboration led to a centuries-long struggle to process thousands of photographic plates taken over decades, hand-measuring the positions of millions of stars to create the largest catalog of the night sky.

Unfortunately, the Carte du Ciel project came at a time when our ability to gather measurements of the natural world was at odds with our ability to analyze them. And while the project was underway, new instruments made it possible to study physical processes in distant celestial objects and lured scientists away from surveying by offering the opportunity to create new models to explain the world.

For the astronomers working on the Carte du Ciel, no model existed that could abstract the positions of millions of stars into a theory about the evolution of our galaxy; Instead, the researchers only had an intuition that photographic techniques might be useful in mapping the world. They were right, but it took almost a century and the entire careers of many astronomers for their intuition to bear fruit.

photography and astronomy

SSPL/Getty Images

It was the astronomer and explorer Francois Arago, President of the Paris Observatory, who introduced the world to the photographic techniques of Louis Daguerre. Building on the work of Nicéphore Niépce, Daguerre discovered how to make permanent images on metal plates.

For centuries, astronomers have struggled to capture what they saw in the night sky with notes and hand-drawn sketches. When looking through the distorted optics of early instruments, it wasn’t always easy to draw what you could see. You might “observe” things that weren’t there at all; Those channels and vegetation on Mars that poor Schiaparelli drew from his Milan observatory were nothing more than an optical illusion caused in part by the turbulent atmosphere. Few very well-trained astronomers like Caroline and William Herschel could instantly discover a new star in a familiar galaxy – a signal of a far-off cataclysmic event?

Photography could change all that. Arago immediately recognized the immense potential of this technique: images captured deep in the night could be conveniently and quantitatively analyzed in daylight. The measurements could be precise and they could be checked repeatedly.

Daguerre received a pension and allowed Arago to make the details of his process publicly available, leading to an explosion of portrait studios in Paris and around the world. But as it turned out, Daguerre’s method just wasn’t sensitive or practical enough to capture anything other than the brightest stars, the sun, or the moon. The next hot new technology, wet-plate collodion emulsions, wasn’t much better; The plates would dry out during the long exposures required to capture faint astronomical objects.

Astronomers had to wait 40 years until the 1880s before very sensitive dry photographic plates were finally available.

#huge #project #map #sky #computers

Leave a Comment