Scientists have discovered something unexpected in the fossilized embryo of a Cambrian worm-like creature: the remains of a tiny, donut-shaped brain in the protozoan’s head.

The approximately 500-million-year-old fossil is an example of marine life Markuelia hunanensisan old cousin of penis worms (Priapulids) and mud dragons (Kinorhyncha). To date, scientists have not found any fossils of the worm-like lunatics in their adult form, but researchers have uncovered hundreds of pristine embryos, capturing various stages of the animals’ early development. Each of these embryos is only about half a millimeter (0.02 inch) in diameter.

“The thing with Mark is, it looks like a mini-adult — it actually looks like a “miniature penis worm,” which gives scientists an idea of what a full-grown penis is M. hunanensis likely looked, Philip Donoghue, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Bristol in England, told Live Science.

Donoghue and his collaborator Xi-ping Dong, a professor at Peking University’s School of Earth and Space Sciences in Beijing, have studied many of these embryos over the years, but this is the first time they’ve found a preserved one Brain fabric hidden inside. They reported their discovery in the Journal on Oct. 4 Open Science of the Royal Society (opens in new tab).

Related: Perfectly preserved dinosaur embryo looks like it ‘died yesterday’

Historically, reports by scientists who have found fossilized brain tissue were controversial because it was previously believed that nerve tissue could not fossilize, Live Science previously reported. In this case, however, the evidence looks compelling, said Nicholas Strausfeld, a regent professor in the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Arizona at Tucson, who was not involved with the study.

“It inevitably seems to me to be a fabric that it isn’t muscle — and it’s not gut either, so what could it be?” Strausfeld told Live Science. “I’d say they’re neurons,” and specifically brain cells arranged in a ring around what would have been the animal’s gut, he said.

The extraordinary embryo was collected from a fossil deposit called the Wangcun Deposit in western Hunan, China. There, the tiny little fossil had been encased in a large slab of limestone. Back in their lab at Peking University, Dong and his colleagues carefully dissolved this limestone with acid and then manually sorted the microfossils in the residue.

“You can imagine any of them [embryos] it probably weighs fractions of a gram, but it literally dissolved tons, metric tons, of rock,” Donoghue said of Dong’s efforts to find these embryos over the years.

After being freed from the limestone, the embryos were transported to the Paul Scherrer Institute in Villigen, Switzerland, which houses a particle accelerator about 400 meters in diameter. By slinging electrons at about the speed of light, the machine creates radiation that can be used for various experiments, Donoghue said. In this case, the team used powerful X-rays generated by the accelerator to take snapshots of their little one M. hunanensis embryos.

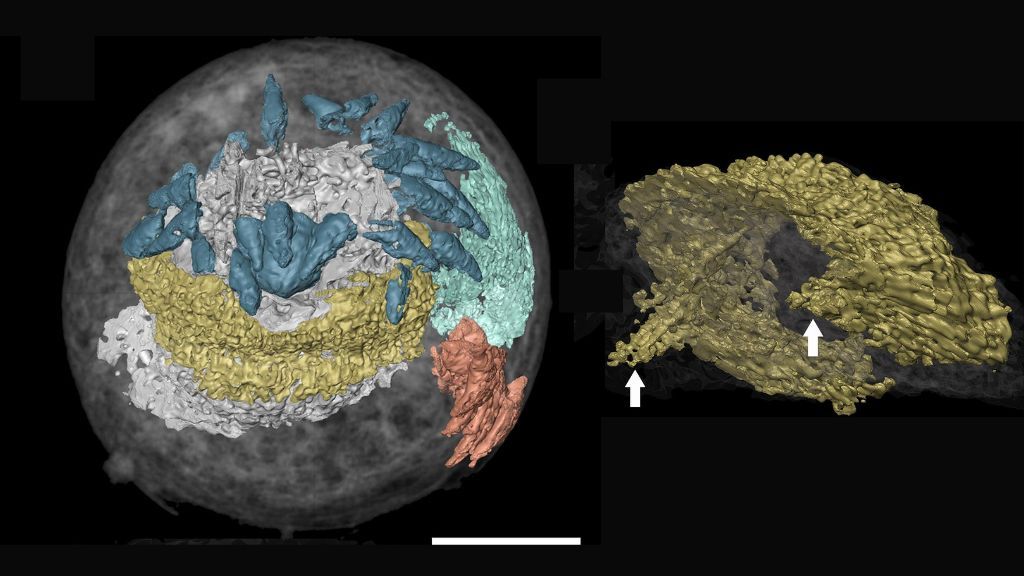

“The sample rotates 180 degrees within the beam, using 1,501 X-rays,” Donoghue said. These individual X-rays can then be stitched together into a detailed 3D model, allowing the team to look inside each embryo without having to physically pry it open.

“Usually we don’t preserve the original anatomy of the organism, we just get the cuticle,” by which he means the hard outer shell of the animal, Donoghue said of the X-rayed embryos. In addition, scientists often see thin lines of mineralization hatching the interior of each embryo; Such lines are believed to be evidence of microbes that grew over the animal prior to its fossilization.

Compared to what the team usually observed, the embryo, which contained traces of nerve tissue, looked completely different. This embryo carried a clear, organized structure in its head, which the team interpreted as the animal’s ring-shaped brain. In addition, the fossil bore another distinctive structure in its tail, which the team thought was muscle debris.

“In this one specimen, we have this completely different, textured and organized tissue of mineralization in both the head and tail that is very different from what we see in any other specimen,” Donoghue said. “So we interpret it as a biological structure inherent in the original organism, and then it’s our job to figure out what it was on Earth.”

Based on the known relationship of M. hunanensis For animals like penis worms and mud dragons, scientists could reasonably expect their brains to be ring-shaped, so the authors’ interpretation of the fossil makes sense, Strausfeld told Live Science. “Aside from the improbability of [the brain’s] fossilization, it would be surprising if it showed a different morphology,” the study authors noted in their report.

Remarkably, this is the first time fossilized nerve tissue has been found in a so-called Orsten fossil, the authors added. Such fossils are usually less than 2 mm long, are found encased in nodules of limestone, and are preserved through a mineralization process in which the animals’ tissues are replaced with calcium phosphate. This process creates a tiny but highly detailed 3D fossil that usually preserves only the animal’s cuticle, not its internal organs.

“Perhaps the most interesting thing about our paper is what it tells us about the potential for future discoveries,” Donoghue said. “Nobody predicted that you could preserve brains or nerve tissue in calcium phosphate, and maybe you just have to go back and look for it in museum drawers.”

#penis #worms #cousin #petrified #donutshaped #brain #intact

Leave a Comment