Photo Credit: Heming Zhang, Author Provided

Some of the world’s most important fossil finds come from China. These include amazing feathered dinosaurs, the earliest modern mammals and some of the oldest known animals on earth.

Four new articles were published in today Nature continue this tradition by unveiling the world’s oldest well-preserved jawfish, dating from 436 million to 439 million years ago to the beginning of the Silurian period.

The fossil finds are all from new fossil sites in Guizhou and Chongqing provinces of China. The Chongqing site was found in 2019 when three young Chinese paleontologists playfully fought and one was kung-fu kicked into the outcrop. Rocks tumbled down revealing a spectacular fossil inside.

The research teams behind the papers are led by Zhu Min of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. Min told me, “The discovery of the Chongqing deposit (a ‘deposit’ is a fossil site of exceptional preservation) is indeed an incredible miracle of fossil hunting. Suddenly we realized that we had found a stunning deposit at the core of the unraveling of the fishy tree of the early jawed vertebrates.”

What were those fish?

Most fish today fall into two main groups:

- Chondrichthyans (which include sharks, rays, and chimeras) have cartilaginous skeletons

- Osteichthyans (bony fish like trout) have bones that make up the skeleton.

The origins of these living groups of fish are now much clearer with the new finds of the oldest complete fish from China.

These were shark-like fish. Some were placoderms, an extinct class of armored fish whose bony plates formed a solid shield around the head and torso.

Others were ancestral species of sharks called acanthodes. These are extinct forms of “ancestral sharks” that evolved as a separate branch – or tribe – of the evolutionary lineage that led to modern day sharks.

Placoderms are the earliest known jawed vertebrates. Their exploration is important as they help uncover the origins of many parts of the human body (including our heart and face).

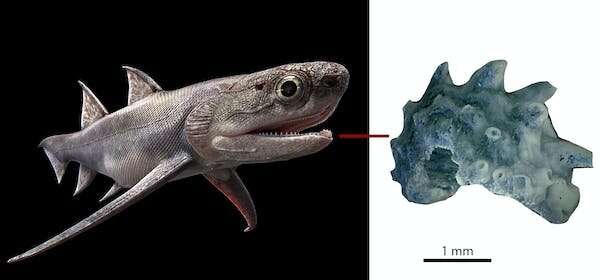

The very small Xuishanosteus is the oldest known placoderm fish. It shows features typical of later Devonian forms. Photo credit: Heming Zhang

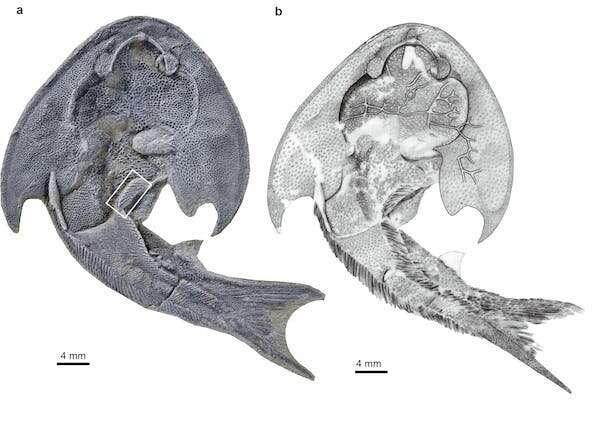

A small flattened placoderm called Xiushanosteusabout three centimeters long, is the most common fish found at the new Chongqing site.

Its skull shows paired bones corresponding to those on our own heads. Forehead and crown bones have their origin in these fish. Zhu You-an, who directed the study of these fish, told me, “All things are still like dreams. Today we stare at complete early Silurian fish, 11 million years earlier than the oldest finds so far! These are both the most exciting as well as the most challenging fossils I’ve had the privilege of working on!”

The oldest sharks and teeth in the world

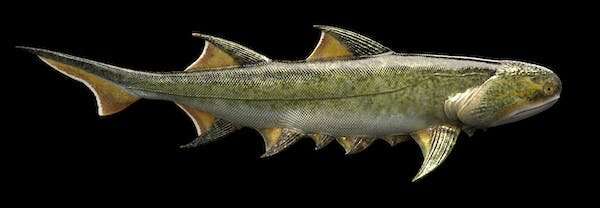

The new papers also describe the oldest complete shark-like fish with the name Shenacanthus. It has a body shape similar to that of other prehistoric acanthodes (or ancestral sharks) – but differs in having thick plates forming armor around it, as seen in placoderms.

The fact that Shenacanthus shares the characteristics of both acanthodes and placoderms suggests that these two groups evolved from similar ancestors. However, Shenacanthus retains the typical shark-like fin spines, so it is not considered a placoderm but rather a chondrichthyan (the group to which modern-day cartilaginous sharks belong).

Shenacanthus is shown here restored. It is the oldest Chondrichthya fish that knows more than just scales. Photo credit: Heming Zhang

The research also reveals the oldest known teeth of any vertebrate – at least 14 million years older than any previous finds. Coming from a fossil chondrichthyan named Qianodus, the teeth are arranged in sinuous rows called “whorls”. Such tooth whorls are common at the juncture of the jaws in many ancient sharks and some early teleosts such as Onychodus.

The researchers also found another early ancestral shark named Fangjinshania at the new site in Giuzhou. More than 300 kilograms of rock were collected and dissolved in weak acetic acid to free thousands of microscopic pieces of bone and teeth.

Fangjinshania resembles a tribe shark named Climatius, which is known to have lived in Europe and North America about 30 million years later. Fangjinshania lived 436 million years ago, which tells us that the fossil record of such sharks is much older than we previously thought.

Both Fangjinshania and Qianodus were about 10 cm to 15 cm long, several times larger than the Placoderms and the Shenacanthus. They would have been the best predators in their ancient ecosystem and the world’s first predators armed with sharp teeth.

Plamen Andreev, the lead author of two of the new articles, told me, “These new finds support the idea that older fossil shark-like scales found in the Ordovician period might now actually be called sharks.”

A reconstruction of Qianodus (left), an early Chondrichthyan fossil, showing the oldest evidence of teeth in any vertebrate. Photo credits: Heming Zhang (graphic) / Plamen Andreev (CT image).

From the fins to the limbs

Another interesting discovery from these fossils concerns the first evolution of paired limbs in vertebrates. A new jawless fish called Tujiiaspis now shows the primitive state of paired fins before separating into pectoral and pelvic fins — the precursors to arms and legs.

Pectoral fins were thought to have evolved in jawless fish called osteostracans, and later pelvic fins in placoderms. But the new Tujiiaspis fossil suggests that both sets of fins may have evolved simultaneously from fin folds that run along the body and end at the caudal fin.

Fanjingshania provides evidence that probably all jawed vertebrates underwent a large evolutionary “radiation” (great diversification) in the Ordovician period more than 450 million years ago. Photo credit: Heming Zhang

When was the first irradiation of jawfish?

Finally, all of these discoveries indicate that the first major “broadcast” of the jaw vertebra (referring to an explosion of diversity) occurred much earlier than anyone had imagined. Ivan Sansom from the University of Birmingham co-authored one of the papers. As Sansom notes, “We had evidence of older material before, but the appearance of well-defined remains of jawed vertebrates so close to the base of the Silurian suggests that jawed and jawless fish coexisted longer than previously thought. There is now evidence of earlier irradiation of sharks and other jawfish in the Ordovician.”

Tujiaaspis fossil (left) and drawing showing the main features. Note the heavy rows of scales that define the lateral “fin fold” area along the body down to the tail. Zhikun Gai et al.

The four publications have shaken up the evolutionary tree, and new diagrams show revised hypotheses about the relationships between living fish. Zhu Min informed me that it will take many years to complete the studies on the new fossils, as several new species have not yet been described in the papers.

We must patiently await the next exciting discoveries to be announced from these extraordinary fossil sites.

Dawn of the Pisces: Early Silurian jawed vertebrates revealed head to tail

Powered by The Conversation

This article was republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Citation: A kung fu kick led researchers to the world’s oldest complete fish fossils. Here’s what they found (2022 October 1st), retrieved October 1st, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-09-kung-fu-world-oldest-fish-fossils.html

This document is protected by copyright. Except for fair trade for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is for informational purposes only.

#kung #kick #led #researchers #worlds #oldest #complete #fish #fossils #Heres

Leave a Comment