As NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope turns its gaze on a sample of the more than 5,000 strange new worlds confirmed to exist in our galaxy, scientists will begin to paint a more complete picture of their “life” – from birth to death Death.

So far, scientists have found that exoplanets – planets outside our solar system – come in a variety of sizes and types. With his ability to reveal never-before-seen details of the universe using infrared light, Webb is likely to end decades of debates about how planets form and die.

From a million miles away, the observatory will measure the composition of exoplanets’ atmospheres and study their structure in three dimensions. And it might give us a better picture of planets like our own – small, rocky, potentially habitable worlds and what it takes to create them.

“We are on the precipice of an explosion in our knowledge of exoplanet atmospheres,” said Johanna Teske, a research associate at the Carnegie Institution of Washington who co-directs a Webb observation team with Natasha Batalha at NASA’s Ames Research Center in northern California.

“We will know something more than just their mass or size and just that they exist,” Teske said. “We’ll start moving the magnifying glass.”

A look at Planetary Nurseries, Youthful Planets

A big question for astronomers: How are planets formed? Webb will use one of his most sensitive instruments, the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), to study the disks of gas and dust swirling around young stars.

Scientists want to understand why these disks appear to have rings and gaps, says Charles Beichman, executive director of the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech and a key player in several Webb observing programs. “Do planets open up these gaps in the formation process?” he asks.

Beichman and other researchers will also look for dusty remnants of planet formation in distant systems to see if they resemble our own Kuiper Belt, the swarms of potential comets in our outer solar system, or the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

A number of programs will target young, high-temperature planets that are still in the process of cooling and contracting after their formation.

A transmission spectrum of a giant, hot exoplanet, WASP-96 b, showing the presence of gases in its atmosphere, including water vapor. The spectrum — from starlight filtered through the planet’s atmosphere — was obtained using the Webb Telescope’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) and was among Webb’s first scientific images to be published.

Using Webb’s MIRI instrument and near-infrared spectrograph (NIRSpec), the research group will collect spectroscopic readings – splitting light from the planets into a spectrum and generating a kind of fingerprint of molecules in the atmosphere of these planets. That should reveal properties like chemistry and the presence of clouds, and provide important clues as to how these giant planets formed.

The Middle Years: Major and Minor Planets

Planets in a mature stage of evolution could tell us whether the properties of planets in our own solar system, even in their middle years, are common or rare.

A Webb observing team plans to probe the depths of a ‘hot Jupiter’, HD 189733 b, observed by other space telescopes. This planet is slightly larger than our own Jupiter and orbits its star so closely that a “year” lasts only 2 days.

The team, which includes Tiffany Kataria, an exoplanet scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, will take these earlier measurements made with the MIRI instrument to the next level. Researchers will perform spectroscopic measurements and ‘eclipse maps’ that capture atmospheric profiles in all three dimensions as the planet passes in front of its star.

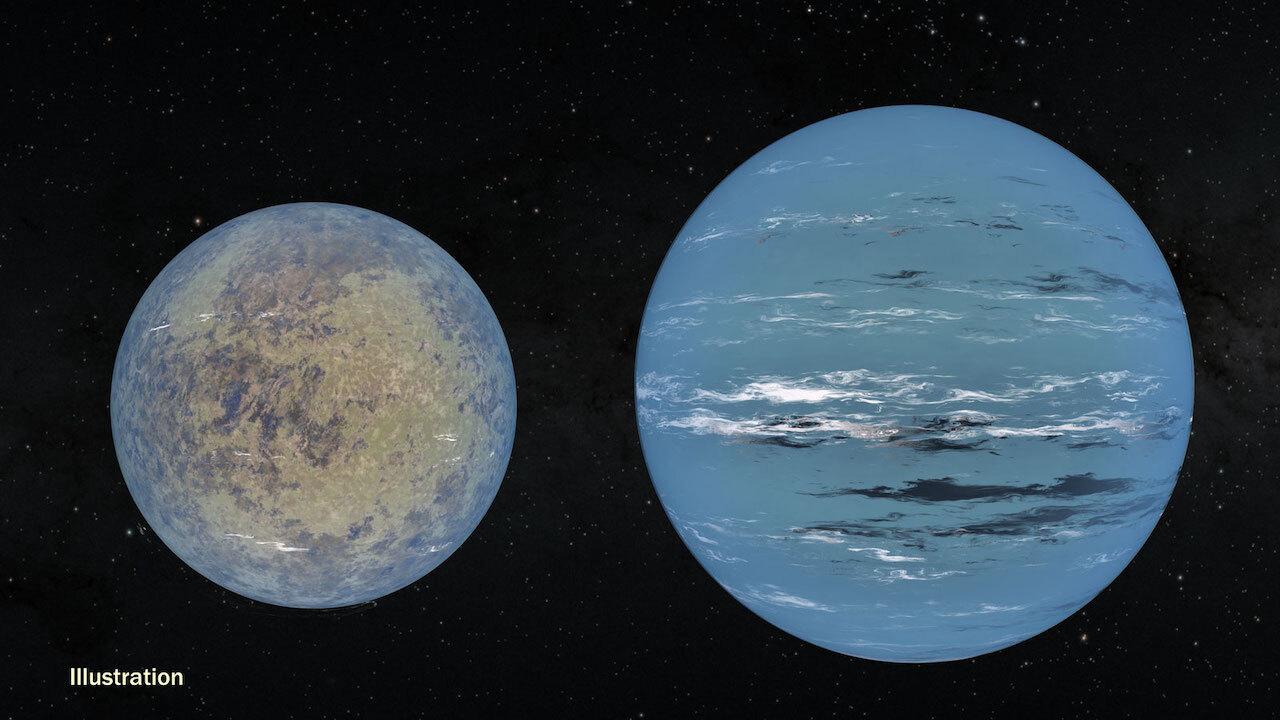

Mature planets include smaller worlds, such as B. Rocky planets the size of Earth, and planets slightly larger but still smaller than Neptune.

Artist’s rendering of the James Webb Space Telescope deployed in space. Credit: NASA/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez

“We are interested in understanding the diversity and atmospheric composition of planets between the size of Earth and Neptune,” Teske said. “’Super-Earths’ and ‘mini-Neptunes’ are the most common types of planets in our galaxy. But we have few examples of atmospheric measurements from these types of planets.”

In the background looms the stubborn question of habitability, particularly in relation to super-Earths. “These planets that are a little bit larger than Earth – could they actually support habitable conditions?” asks Teske.

Previous space telescope surveys have spotted rocky planets about the size of Earth orbiting small, comparatively cool red dwarf stars.

Webb will look for atmospheres in a famous planetary cluster called TRAPPIST-1: seven roughly Earth-sized planets in close orbit around a star less than 10 percent the size of the Sun. A science program will focus on TRAPPIST-1e, orbiting in the center of TRAPPIST-1’s habitable zone. Using NIRSpec, a team led by Cornell University’s Nikole Lewis will try to get spectroscopic readings of the planet’s atmosphere – if there is one at all.

After the sinking, a second life for some planetary systems?

One of the least-explored areas of exoplanet existence is the final stage. However, a recent startling discovery revealed a planet orbiting a white dwarf — the shriveled shell of a bygone star.

An observing team led by Cornell scientist Ryan MacDonald will use NIRSpec to search for the signature of an atmosphere around this Jupiter-sized planet – a dry run on an even more intriguing question.

“I’ve been working on the prospect of habitable planets around white dwarfs for many years,” he said. This includes searching for “biosignatures” – signs of active biology – on planets in systems now thought to be dead.

The Webb telescope observations promise an exponential expansion of knowledge—entire exoplanet biographies, from birth to death to resurgence.

“The goal is to take steps toward a better understanding of these planets, not just on a planet-by-planet basis, but as an overall population,” Teske said. “JWST’s unprecedented capabilities will help make this possible and usher in a new era of exoplanet exploration.”

#Exoplanets #NASA #Webb #telescope

Leave a Comment