Pictures by Kerstin Joensson. Video by Denise Hruby and Kerstin Joensson

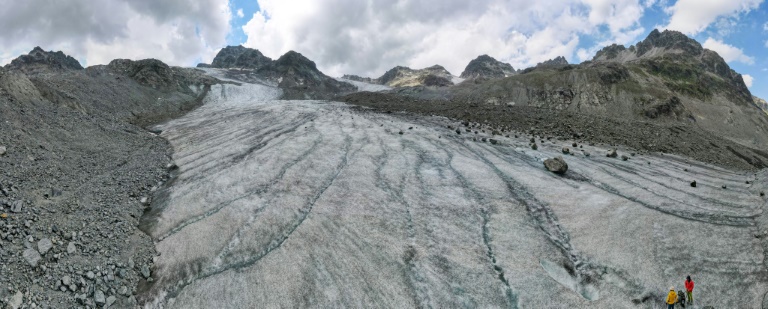

Leaping from rock to rock across a stream formed by Austria’s Jamtal Glacier, scientist Andrea Fischer fears valuable scientific data will be irretrievably lost as snow and ice melt faster than ever.

“I could not have imagined that it would ever melt as dramatically as it did this summer… Our ‘archive’ is melting away,” says the glaciologist.

Fischer – deputy director of the Institute for Interdisciplinary Mountain Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences – has spent more than 20 years examining the Jamtal and four other Alpine glaciers across Austria’s highest peaks for the oldest ice sheets.

For scientists trying to reconstruct Earth’s climate in the distant past, such ice formations are a unique time capsule going back thousands of years.

Glaciers hold an invaluable treasure trove of data — as they grew, the ice encapsulated twigs and leaves that can now be carbon-dated, Fischer explains.

And based on the age of such material and the depth at which it was found, scientists can infer when ice grew during colder periods or when warmer conditions caused it to melt.

But now the glaciers are melting rapidly – including that in the remote and narrow Jamtal, not far from where tourists found the amazingly well-preserved 5,300-year-old mummy of Ötzi, the Iceman, in the 1990s.

According to the International Commission for the Protection of the Alps (CIPRA), temperatures in Europe’s highest mountains have risen by almost two degrees Celsius over the past 120 years – almost twice the global average.

Since then, the approximately 4,000 glaciers of the Alps have become one of the clearest signs of global warming.

“If things continue like this, the Jamtal Glacier will no longer be a glacier in five years,” says scientist Andrea Fischer

KERSTIN JOENSSON

The Jamtal Glacier is losing around a meter of surface area every year, but more than a meter this year, says Fischer.

“And we’ve got at least two months of summer left… where the glacier is fully exposed to the sun,” she warns.

Snow normally shields most of the glacial ice from the sun until September, but what little snow fell last winter had melted by early July.

“This year is unprecedented compared to the average of the past 6,000 years,” says Fischer.

“If things continue like this, the Jamtal Glacier will no longer be a glacier in five years.”

Fischer fears that by the end of the summer, around seven meters below the surface will have melted – or around 300 years of climate “archives”.

“We need the data from the glaciers to understand the climate of the past – and to create models of what awaits us in the future,” she says.

Fischer and her team have drilled on both the Jamtal and other nearby glaciers to extract data, taking ice samples from as deep as 14 meters.

As temperatures rise and glaciers become more unstable, they are forced to take extra safety precautions – 11 people died in a glacial ice avalanche in the Italian Dolomites in July, a day after temperatures there soared to new records.

In Galtür, the town closest to the Jamtal with 870 residents who are mostly dependent on tourism, the Alpine Association is already offering a “Goodbye, glacier!” Tour of the once ice-filled valley to raise awareness of the effects of climate change.

Where the ice has retreated, scientists found that about 20 species of plants, mostly mosses, have taken control over a three-year period. According to Fischer, larches grow in some areas.

In Galtür, the closest town to the Jamtal Glacier, the Alpine Club is already offering a “Goodbye, Glacier!” trip

KERSTIN JOENSSON

“It will be a pity if the glacier is gone in five years, because it is part of the landscape,” says Sarah Mattle, chairwoman of the Alpine Club.

“But then there are also new paths, and perhaps there is an easier hike over the mountains than over the ice. It will all be a question of adjustment,” adds the 34-year-old.

Other locals are heartbroken, such as Gottlieb Lorenz, whose great-grandfather was the first caretaker of the 2,165-meter-high Jamtal Hut, which was built as a refuge for mountaineers.

He points to an 1882 black-and-white photograph showing a thick sheet of ice flowing past the hut.

Today, the ice is a 90-minute hike away.

#Austrian #scientists #unravel #mysteries #melting #glaciers

Leave a Comment