A sharp eye in the sky is helping scientists spy on “super-emitters” of methane, a greenhouse gas about 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

That observer is NASA’s Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation Instrument, or EMIT for short. EMIT was Mapping the chemical composition of dust in the desert regions of the earth since installation on the outside of the International Space Station (ISS) in July to help researchers understand how dust in the air affects climate.

This is the main objective of EMIT’s mission. But it also makes another, less-anticipated contribution to climate studies, NASA officials announced on Tuesday (October 25). The instrument identifies huge heat pockets methane Gas all over the world – already more than 50 of them.

Related: Climate change: causes and effects

“Limiting methane emissions is the key to containment global warming. This exciting new development will not only help researchers better pinpoint where methane leaks are coming from, but also provide insight into how to address them — fast,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement (opens in new tab).

“The International Space Station and NASA’s more than two dozen satellites and instruments in space have long been invaluable in determining changes in Earth’s climate,” added Nelson. “EMIT is proving to be a crucial tool in our toolbox to measure this potency greenhouse gases – and stop it at the source.”

EMIT is an imaging spectrometer designed to identify the chemical fingerprints of a variety of minerals on the Earth’s surface. The ability to also detect methane is kind of a happy accident.

“It turns out that methane also has a spectral signature in the same wavelength range, and that’s what allowed us to be sensitive to methane,” said EMIT principal investigator Robert Green of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California during one press conference on Tuesday afternoon.

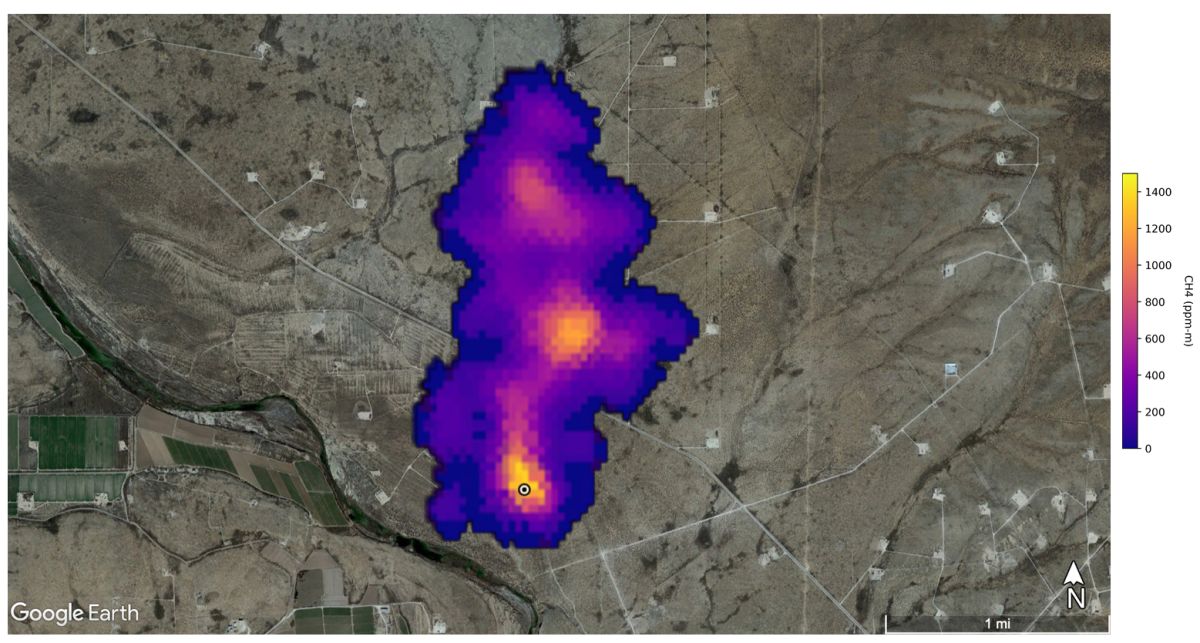

Green and other members of the EMIT team gave some examples of the instrument’s sensitivity during Tuesday’s media briefing. For example, the instrument detected a plume of methane at least 4.8 kilometers long in the sky over an Iranian landfill. This newly discovered super-emitter pumps about 18,700 pounds (8,500 kilograms) of methane into the air every hour, the researchers said.

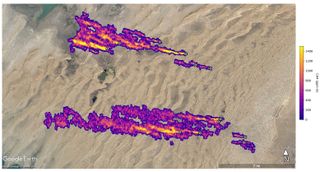

That’s a lot, but it pales in comparison to a cluster of 12 super-emitters EMIT spotted in Turkmenistan, all linked to oil and gas infrastructure. Some of these plumes are up to 32 km long and together add about 50,400 kg of methane earth atmosphere per hour.

That compares to the peak rates from the Aliso Canyon leak, one of the largest methane releases in US history. (The Aliso Canyon event, which occurred at a methane storage facility in Southern California, was first noticed in October 2015 and was not fully plugged until February 2016.)

EMIT discovered all of these superemitters very early on, during the testing phase of the instrument. So it should make even greater contributions when it becomes fully operational and scientists become more familiar with the instrument’s capabilities, team members said.

“We’re really just scratching the surface of EMIT’s potential for mapping greenhouse gases,” said Andrew Thorpe, a research technologist at JPL, during Tuesday’s news conference. “We’re really excited about EMIT’s potential to reduce emissions from human activities by locating those sources of emissions.”

Mike Wall is the author of “Out there (opens in new tab)(Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for extraterrestrial life. Follow him on Twitter @michaelwall (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).

#Methane #super #emitter #discovered #Earth #space #station #experiment

Leave a Comment