Tonga’s volcanic eruption in January blasted enough water to fill more than 58,000 Olympic-size swimming pools – and could weaken the ozone layer.

Scientists studying the amount of water vapor expelled from the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano called it “unprecedented.”

The powerful steam was created when seawater in the South Pacific came into contact with the lava and became “superheated”.

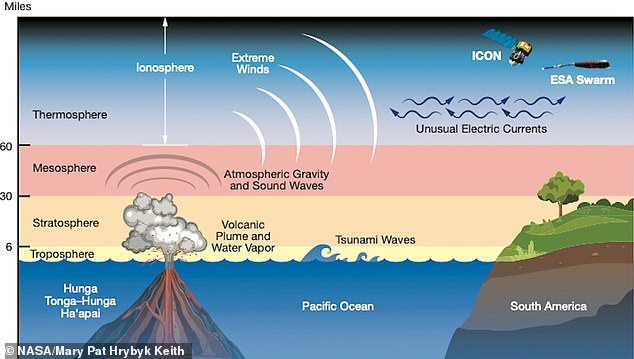

The eruption created sound waves that could be heard as far away as Alaska 6,200 miles away in a sonic boom that circled the globe twice.

In a new study, experts at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory predict the volume of water could be enough to temporarily affect the average global temperature.

It could also temporarily enhance chemical reactions in the atmosphere that exacerbate ozone depletion.

“We’ve never seen anything like it,” said atmospheric researcher Dr. Luis Millan.

In a new study, experts at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory predict the amount of water ejected during the eruption could be enough to affect the global average temperature

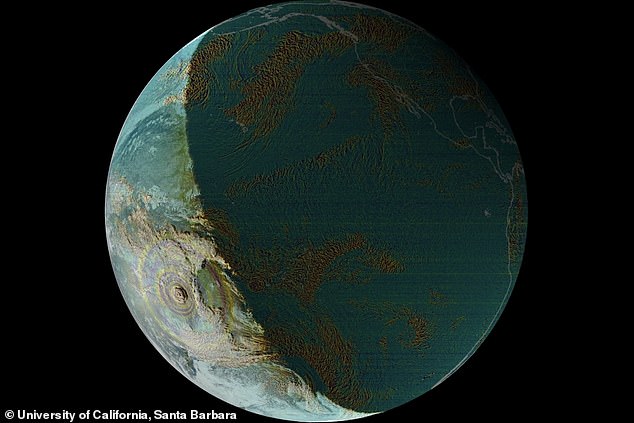

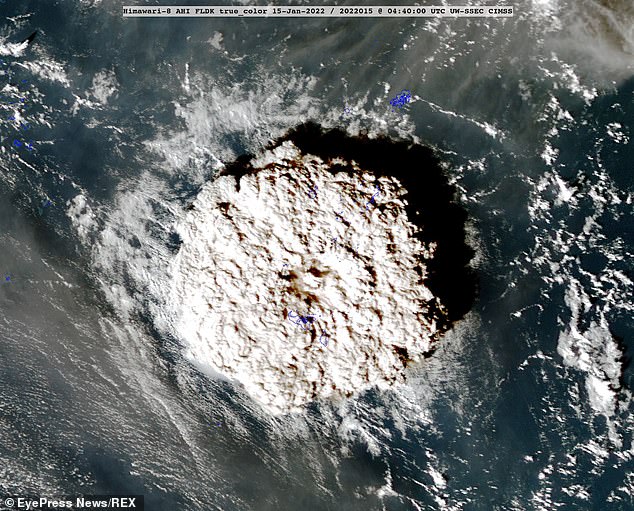

Just before night hit Tonga, the burst (bottom left) produced sound waves that could be heard as far as Alaska 6,200 miles away in a sonic boom that circled twice the globe

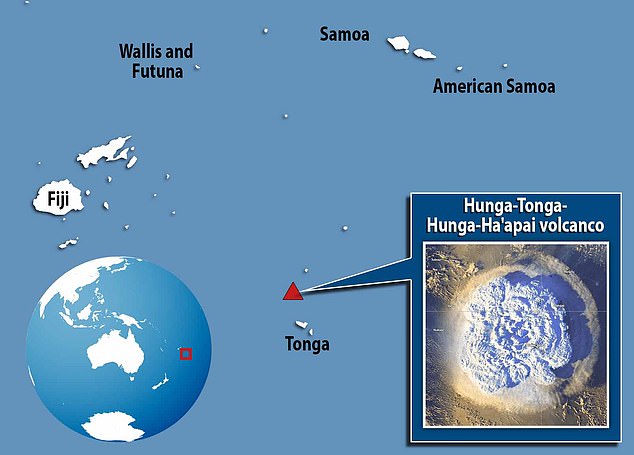

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, an underwater volcano in the South Pacific, spewed ash and other debris up to 40 kilometers into the atmosphere when it erupted in January

In the study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, Dr. Millán and his colleagues that the Tonga eruption ejected around 146 million tons of water vapor into the stratosphere.

The stratosphere is the layer of the atmosphere between about 8 and 33 miles (12 and 53 kilometers) above the Earth’s surface.

The water from the January 15 eruption is about 10 percent of the water content already present in the stratosphere.

Comparable amounts of water have only been blasted to such great heights by volcanoes twice in the 18 years that NASA has been taking measurements.

These were the 2008 Kasatochi event in Alaska and the 2015 Calbuco eruption in Chile.

The water from these events quickly dissipated, but NASA researchers claim the fluid from the Tonga volcano could remain in the stratosphere for up to 10 years.

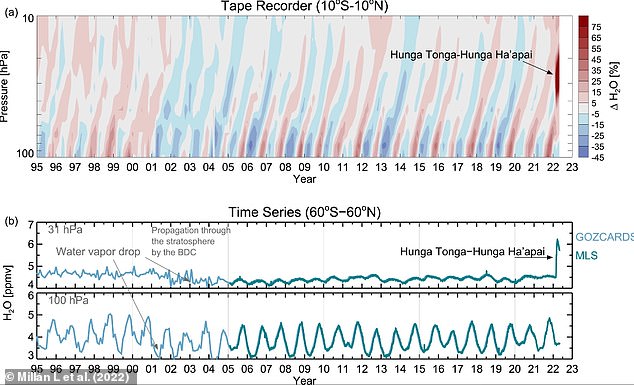

A: The water vapor reached the stratosphere mainly in the tropics, where dry and humid air rises in annual cycles. The eruption’s vapor disrupted this “heartbeat” signal. B: Time series of near-global water vapor at atmospheric pressures of 100 and 31 hPa using data from MLS and GOZCARDS

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption caused many effects, such as atmospheric waves, extreme winds and unusual electric currents, which were felt around the world and in space

To determine the volume of water vapor, scientists analyzed data from the Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) instrument on NASA’s Aura satellite.

This measures atmospheric gases, including water vapor and ozone, by observing natural microwave signals emitted by the Earth’s atmosphere.

The researchers found that readings increased dramatically after the Tonga volcano erupted.

dr Millán, who manages the instrument in Pasadena, California, USA, said: “We had to carefully examine all measurements in the cloud to ensure that they could be trusted.

“MLS was the only instrument with sufficient coverage to capture the plume as it happened and the only one unaffected by the ash the volcano released.”

As the water molecules break down in the stratosphere, they release reactive hydrogen oxide molecules.

These react with ozone and destroy it themselves, but also convert chlorine-containing gases into other destructive molecules.

Water vapor also traps heat, so the eruption could result in a temporary warming effect on Earth’s surface, which researchers believe is the first time.

Although counted as a “greenhouse gas” like carbon dioxide and methane, warming would not be enough to amplify the effects of climate change.

This is because the heat would dissipate as the extra water was naturally channeled out of the stratosphere.

Conversely, previous massive volcanic eruptions like Krakatoa have thrown ash, dust, and gases into the atmosphere that reflect sunlight back into space, creating a cooling effect.

In the paper, Dr. Millán: “It is crucial to monitor the volcanic gases from this eruption and future ones to better quantify their different roles in climate.”

Researchers believe the Tonga volcano was only able to produce the massive amounts of water vapor it did because of its precise depth underwater.

Its caldera – the large crater formed when magma erupts – is believed to be around 150 meters deep.

If it were shallower, there wouldn’t have been enough seawater superheated by the magma to account for the volume of stratospheric water vapor.

However, any depth and ocean pressure could have dampened the violent eruption.

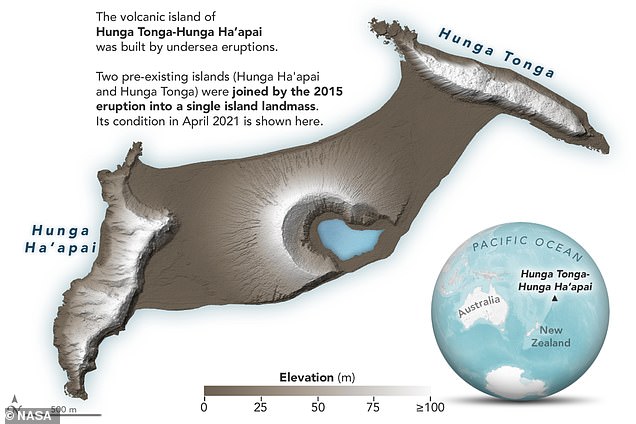

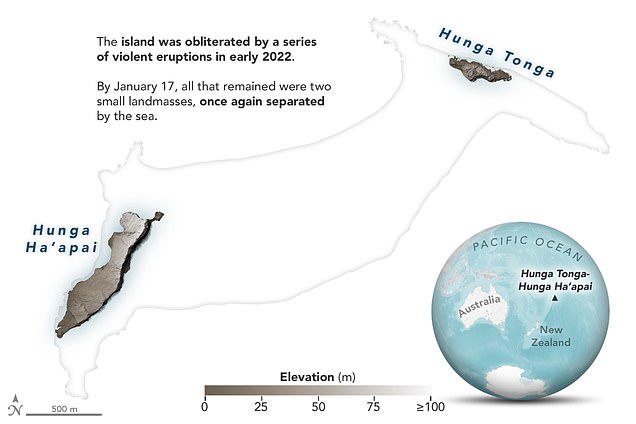

Radar surveys before and after the eruption show that only small parts of two uninhabited Tongan islands above the volcano – Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha’apai – remain

#Water #Tongas #underwater #volcano #weaken #ozone #layer #scientists #warn

Leave a Comment