Toronto –

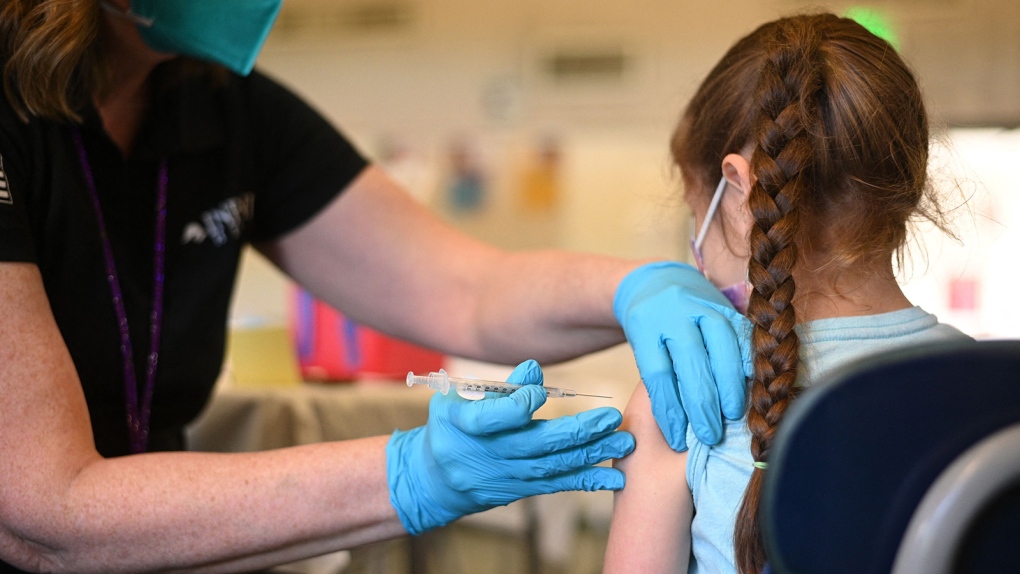

The relatively low spread of the flu over the past two years puts young children at greater risk than usual of contracting it this fall and winter, say experts, who also fear less pandemic measures and reduced immunization uptake will spread further.

To a lesser extent, adults’ resistance to influenza is also lower than usual because fewer people have received the immune boost of a recent winter infection, says Dr. Infectious Disease Specialist Susy Hota, stressing the added importance of flu shots this season.

“Our immune responses are boosted to some degree when we see these viruses more frequently,” explains Hota, the University Health Network’s medical director for infection prevention and control.

“We haven’t really had that in the past two years. So people could get more symptomatic and pick up these infections and notice them more over the next few years.”

Necessary pandemic measures to limit the spread of COVID-19 resulted in just 69 confirmed flu cases in the 2020-2021 season and only sporadic cases in 2021-2022, according to a recent update from the National Advisory Committee on Immunization, which monitors the Public Health Agency advises Canada on vaccine deployment.

The pool of potential flu patients this fall and winter is larger, as are masks and social distancing, says immunologist Dawn Bowdish of McMaster University in Hamilton.

“As a population, we are ripe for influenza,” she says. “One of the reasons it seems to be spreading a little earlier than some sort of pre-COVID year is because there are just so many vulnerable people who can harbor this infection.”

Like Hota, she says the potential increase in circulation in the coming months is “a really big concern” for children under the age of two, who are being exposed for the first time and are more susceptible to serious illnesses.

The same is likely true for children as young as three and four, who otherwise might have caught the flu as babies or toddlers but would have been spared due to COVID-19 containment strategies, she adds.

“Because we’re dealing with a whole bunch of kids who haven’t had a lot of stimulation… we can expect it could be really problematic with young kids this year,” says Bowdish.

She notes that a similar scenario played out last summer, when a wave of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) sent infants, toddlers and preschoolers to the hospital and strained pediatric health care resources.

While myriad other stresses continue to weigh on the healthcare system — including ongoing COVID-19 infections, which many experts fear will also rise — getting the flu shot this year is especially important, Bowdish adds.

When it comes to flu risk for the entire population, infectious disease expert Matthew Miller doesn’t expect that missing a flu season will make us significantly more vulnerable than in previous years.

Miller, the director of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research at McMaster, says many adults can rely on some level of immunity that comes from a lifetime of exposure to seasonal influenza, including seniors, who are generally not so immune responses are stronger than younger age groups.

This immunity can last for years and even decades if someone encounters a strain of influenza that is closely related to something they have previously seen.

“During the swine flu pandemic, seniors were disproportionately protected from death because this virus looked very similar to the virus that caused the 1918 Spanish flu,” says Miller, also an associate professor of biochemistry and biomedical sciences at McMaster.

“People who were very old and exposed to the 1918 Spanish flu and similar viruses that circulated shortly after that year actually had protection until 2009.”

There have been cases where the same strain has been recirculating for several years, but when it changes, that pre-existing immunity becomes much less effective, Miller says.

Thanks to pandemic measures that also protected most people from catching the flu, Bowdish says the current circulating influenza species are very different than they were before the COVID-19 outbreak.

“Because of all the social distancing (and) masking, many lineages of the flu virus have actually become extinct,” she says.

Clues to this season’s dominant strain can be found in what’s circulating in the southern hemisphere, Miller says, noting that most of the time we can expect the same version to show up in Canada.

“But it’s not always what happens in practice because of course there are gaps between the Australian season and our season and the dominant virus can change in the meantime,” he adds.

Still, Miller says it’s likely someone who got sick in 2019 will have some protection this season as he believes any changes from this year’s flu will be “modest”.

While countries like Australia, New Zealand and South Africa have been hit particularly hard, Bowdish says it’s not clear whether this is because the virus itself developed particularly problematic mutations, vaccination rates were too low, or the vaccine didn’t match the strain very well.

The Canadian Pharmacists Association’s Danielle Paes points to a worrying survey of 1,500 adults in August in which just 50 percent of respondents said they would get an injection this year, down six points from a survey in 2021. The margin of error is plus or minus 2.53 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

Paes says the waning interest in the flu shot could also worsen the impact of the flu this season.

Hota points to the resumption of many pre-pandemic activities as a key factor behind flu infections this season, noting that mask requirements have fallen, people have resumed travel and are gathering indoors again.

“In years past we’ve had public health measures and some kind of restrictions on movement or socialization or people’s ability to congregate,” she says.

“This year is definitely different.”

#Experts #warn #young #children #greater #risk #catching #flu #season

Leave a Comment